[caption id="NewtonandCowper_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

THE COWPER AND NEWTON MUSEUM,OLNEY, UK

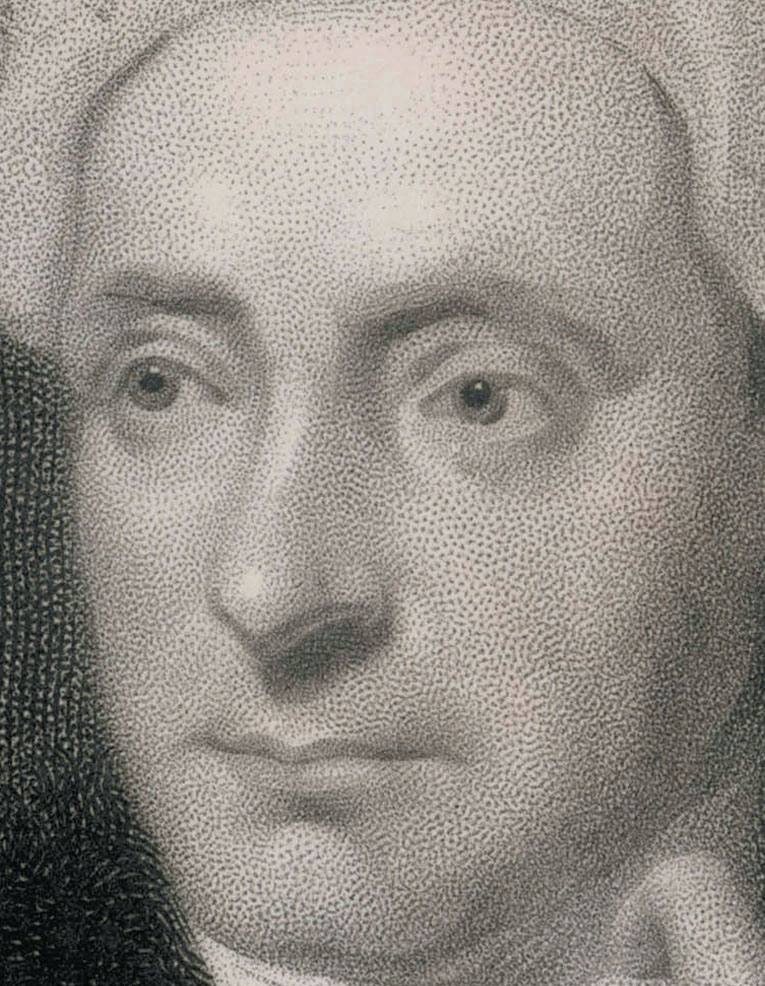

[caption id="NewtonandCowper_img1" align="aligncenter" width="765"]

[caption id="NewtonandCowper_img2" align="aligncenter" width="765"]

Mary Evans Picture Library

“AMAZING GRACE, HOW SWEET THE SOUND, THAT SAVED A WRETCH LIKE ME.”

No words are better known in Christian hymnody than those of “Amazing Grace.” John Newton’s 18th-century lyrics must be the most widely recognized hymn in the English language. In addition to its singable and moving tune, the soulful yet ultimately triumphal lyrics sum up the gospel of the evangelical faith. It was a faith shared by the writer and his closest friend, the pastoral poet William Cowper (pronounced Cooper).

“Amazing Grace” was first published in 1779, in a collection called The Olney Hymns. The book contained 348 hymns written over 10 years by Newton or Cowper. During that decade the close friends lived a half-mile apart in the Buckinghamshire market town of Olney (now famous for its Shrove Tuesday Pancake Race). Newton was the curate of the parish church of St. Peter and St. Paul and an ardent proponent of the evangelical faith preached by George Whitefield and the Wesleys.

Born in 1725, John Newton hardly took the traditional 18th-century route to holy orders and the genteel life of the rural clergy. As a young man, Newton was a merchant sailor, rising in the ranks to captain his own ship, plying the Atlantic waters in the slave trade out of Africa. Newton’s ship carried slaves like so much other cargo. One day a North Atlantic storm threatened his ship and his life, and in a desperate moment Newton prayed to God, pleading for his physical salvation.

Not unlike many of those who have found themselves in deadly peril and bargained with God for life, Newton kept the promise he made. He abandoned the slave trade and at the young age of 31 became tide surveyor (customs officer) at the port city of Liverpool, with some 60 men under his direction. It was God’s call and his gratitude to God, however, that now propelled Newton’s life. Soon he was studying, sharing the story of his own experience and preaching all over the area.

[caption id="NewtonandCowper_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

PICTURE CREDIT GOES HERE.

Newton’s conviction and the power and simplicity of his preaching gained him something of a reputation. In 1764 Newton wrote a spiritual autobiography titled An Authentic Narrative, which was brought to the attention of the Earl of Dartmouth. An influential evangelical peer, Lord Dartmouth was much taken with Newton and subsequently offered him the curacy at Olney. With the keen support of the earl, the evangelically ardent, uneducated ex-slave trader was ordained that year by the Bishop of Lincoln and made his way to the church of St. Peter and St. Paul. For the first time truly away from the sea and his past, Newton never lost the intensity of his gratitude to God for saving his life and rescuing his soul.

NEWTON AND COWPER WERE REMINISCIENT OF THE BIBLICAL DAVID AND JONATHAN. COWPER WAS FRAGILE AND REFINED, WHILE NEWTON WAS TOUCH AND CERTAIN OF HIMSELF.

William Cowper’s path to Olney was altogether different. From a well-connected family of gentry, Cowper was a very bright, extremely sensitive boy, sent off after his mother’s death to the rough world that was English boarding school life in the 18th century. He was bullied, abused and miserable. After finishing at Westminster School, he went on with family encouragement into law, and though his enthusiasm and talent lay in literature and writing poetry, he eventually entered the Inner Temple as a barrister. But all was not well in Cowper’s head or heart.

In 1757 Cowper’s father died, his closest friend drowned and the family firmly interrupted the love relationship that he had with his cousin Theadora. He was driven into a lasting depression. In early 1763 Cowper was appointed to a position in the House of Lords and halfheartedly prepared for his oral examination before a committee of peers. But Cowper could not face the anxiety of that experience. Lonely and increasingly depressed, he attempted suicide unsuccessfully on several occasions. That December, the family put the 32-year-old poet and lawyer in Dr. Nathaniel Cotton’s Collegium Insanorum in St. Albans. Cowper felt that not only was his life over but also that God had abandoned him.

Cowper spent a year and a half at the private sanitarium. Cotton, highly respected as a physician, was something of a successful poet himself and took a particular interest in Cowper. In addition, the doctor was an earnest Christian, and his ministrations reached Cowper spiritually as well as psychologically. During his stay at the college, Cowper had a conversion experience, meeting Jesus, if you will, on the road to Damascus. He was a changed man. Gone was his spiritual angst and the overbearing sense of guilt and other symptoms that today would be diagnosed as severe major depression. In the next months, Cowper wrote a number of poems that described his early turmoil of mind and soul and his thankfulness to God for the peace that he now felt. He was ready to leave Collegium Insanorum.

William Cowper’s brother John set him up in Huntingdon, where he was soon “adopted” by the Rev. Morley Unwin, the parish vicar, and quickly accepted by Unwin’s wife, Mary, and their two children as one of the family. He joined their household as a paying guest. For the first time in his life, he was truly happy. Unwin nurtured Cowper’s young Christian faith, and Mary provided the maternal nurturing he had lacked since his own mother died.

Two years later when the Rev. Unwin died after being thrown from a horse, the Rev. John Newton rode over from Olney to console the widow of a brother vicar. Mary Unwin was most impressed by Newton, and the story goes that John Newton and William Cowper, as soon as they met, instantly and mutually felt a total affinity for each other. In September 1767, Mary Unwin, her daughter Susannah and her dear friend and lodger Cowper moved to Olney in order to “sit under” the preaching and ministry of Newton.

At first glance, Newton and Cowper must have seemed like a pair reminiscent of the biblical David and Jonathan. Cowper was pale, fragile and refined, while Newton was leathery, tough and certain of himself. However, they had much in common. Both expressed themselves in poetry, had lost their mothers early and been close to death several times. Both had a dramatic conversion experience, an encounter with God that changed and charged their lives. They shared an evangelical faith and a deep personal love for God. And both felt a keen delight in nature.

William Cowper and Mary Unwin settled in a brick house called Orchard Side on the market square. Behind the public-facing edifice lay an expansive T-shaped garden and orchard beyond. Across that orchard sat the vicarage, inhabited by John Newton and his wife, Mary.

[caption id="NewtonandCowper_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

THE COWPER AND NEWTON MUSEUM,OLNEY,UK

NEWTON AND COWPER EACH PRODUCED A STEADY STREAM OF HYMNS PRAISING GOD.

A well-worn path soon lay across the orchard between the homes, and rare was the day when the men did not spend hours together. They often walked the gentle and idyllic countryside, following the River Ouse through the seasons of the year. In clement weather they spent hours discoursing in the summer house in Cowper’s garden. In the darkling of winter, they mused before the parlor fire. Perhaps the key to their intimacy lay in a shared bond—the belief each of them held that they were the wretch of the “Amazing Grace” opening verse.

Over the years from 1767 to 1779, Cowper’s depression periodically returned, ebbing and flowing, and sometimes rendering him incapable of reasoned conversation for months at a time. Newton’s ministry and local reputation ebbed and flowed as well. At the height of his popularity, parishioners flocked to the vicarage for prayer meetings, the only place big enough to hold the crowds.

[caption id="NewtonandCowper_img5" align="aligncenter" width="503"]

THE COWPER AND NEWTON MUSEUM, OLNEY, UK

[caption id="NewtonandCowper_img6" align="aligncenter" width="502"]

THE COWPER AND NEWTON MUSEUM, OLNEY, UK

[caption id="NewtonandCowper_img7" align="aligncenter" width="503"]

COURTESY OF DANA HUNTLE

Throughout those years, Newton and Cowper each produced a steady stream of hymns praising God, basing their lyrics primarily on Bible passages from Genesis to Revelation. Nearly every week, a new hymn by one of them was introduced at the vicarage prayer meeting.

William Cowper and John Newton knew they were not writing “poetry.” They were writing hymns. Absent from their verse were the conventions, metaphors and stylized language of the formal poetry of the day. The language of their lyrics was simple, designed to be understood by the common people. Most important, perhaps, both Cowper and Newton were good enough craftsmen with the language to write verse that could be sung.

By the time The Olney Hymns made its appearance in 1779, a number of the hymns were already being circulated. The book was an instant success, its reputation spreading quickly, and it was reprinted a number of times over the next few years. Indeed, many of those hymns survive to this day, sung regularly by churchgoers everywhere. While “Amazing Grace” is certainly the most popular, “There Is a Fountain Filled With Blood,” “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken,” “How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds” and “May the Grace of Christ Our Savior” are only a few of the other recognizable titles first published in the hymnal.

[caption id="NewtonandCowper_img8" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

The Cowper and Newton Museum, Olney, UK

As the collection was printed in 1779, Newton became convinced that his ministry in Olney was done. At the end of that year, John and Mary Newton moved to London, where John took the largest church with an allegiance to the evangelical movement, St. Mary Woolnorth. Cowper and Newton’s friendship remained intact, though they did not often see each other. As a preacher, counselor and sage, Newton soon became one of the most influential clergymen in the capital. Most significant from a historical perspective, perhaps, it was Newton whose counsel and friendship inspired his young friend William Wilberforce to take up the abolition of slavery as a life cause.

Newton returned to Olney for the last time in 1792, but he could not bear to return again—for the pain of happy memories of his years there with Cowper. Until near his death in 1807 at 82, though increasingly deaf and blind, Newton preached and counseled.

Cowper went on to become a popular poet of his time, though his work is not read much today. Often incorporating the spiritual themes of his life, his poetry is also full of the Buckinghamshire countryside, nature and the rhythms of the agricultural year. Among the most famous works in his lifetime, though, was a set of ballads written at Newton’s behest in the cause of the abolitionist movement. William Cowper and Mary Unwin remained in Olney until her paralyzing strokes caused them to move to the village of Weston Underwood, and in 1796 to Norfolk. Cowper died a celebrated poet in 1800.

Cowper and Newton had shared a camaraderie and bond that lasted even through their last 20 years as friends following Newton’s move to London. Both men died peacefully and secure in the faith that had motivated their lives. They leave a legacy celebrated every Sunday morning around the globe.

IF YOU GO

Orchard Side, the house on the Olney market square where William Cowper and Mary Unwin lived from 1767 through the years of Cowper’s daily friendship with John Newton, with the 18th-century gardens that Cowper created and loved, is now the Cowper and Newton Museum, a private, nonprofit board-governed museum. The museum is open from March 1 until mid-December, from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. and 2 to 5 p.m., Tuesday through Saturday, and Sunday afternoon in the summer as well.

Olney lies on the A509, an easy five miles north of the M1, junction 14. It straddles the River Ouse between Newport Pagnell and Wellingborough, in the home county of Buckinghamshire. The vicarage the Newtons inhabited still lies across the meadow from Cowper’s garden, and it is a privately occupied vicarage. The parish church of St. Peter and St. Paul sits across the street. It is open most daylight hours. Newton’s pulpit survives in place, and the entire building is little changed from the years when he occupied it. Newton’s grave lies in the churchyard, in a far back corner, marked by a simple monument.

Comments