[caption id="NostalgiaIsntWhatItUsedToBe_img1" align="aligncenter" width="261"]

IF MEMORY SERVES ME CORRECTLY, a pint at the pub cost about 30p the first time I visited Britain in 1973. Now, in London at least, it’s apt to cost three quid. Ah, for a simpler time.

Somehow we take for granted the extraordinary blessings of a quality of life that has changed so dramatically for the better over the last three generations. Yet we moan without ceasing for the loss of a way of life past—the social cohesion, sense of belonging, customs and traditions of a bygone time. Of course, all memory is selective.

Among the changes that have been mourned across Britain over the last 20 years is the decline and fall of the villages. Alas, it’s true. Post office closings are announced on a routine basis; they just aren’t cost-effective in the villages any more. Thousands of small communities have lost their village schools and local shops—often little more than convenience stores. And village pubs have been on the decline, too. It’s just as easy to hop in the car and head to the market town for an evening out.

‘Many people lived their lives without traveling 20 miles from their birthplace and knew little of the world’

Unhappily, the cute little self-contained villages of thatch and stone cottages and tidy gardens, parish fetes and the like have largely disappeared as a way of life. Nowadays, villages are simply bedroom neighborhoods for pensioners and commuters. The village isn’t the center of life anymore. But to be fair, where are the means of making a living in the villages?

The conditions of life that created those villages in the first place no longer exist. When life was subsistence and agrarian, men and families from each village farmed a strip or two of land on its periphery, kept a few fowl and animals, tended cottage gardens and paid their rent with sweat equity. It might sound pastorally innocent and picturesque, but it wasn’t fun.

Until the rise of industrialization in the 19th century, life throughout Britain had remained essentially unchanged for 400 years or more. In the home, in the fields, in the villages and market towns, the incremental changes in goods and transport, material well-being and medicine, diet and tools of any trade during any person’s lifetime were few, and each one in itself was remarkable. The standard of living one anticipated was little different from generation to generation.

Almost everyone lived on the land; few people owned it. Many people lived their lives without traveling 20 miles from their birthplace, and knew relatively little of the world beyond those boundaries. The vicar or local curate might be the only literate person in the community. The small handful of distant aristocracy or incidental gentry were simply another world, who impacted life most when they led the village men to war.

If life was difficult and physically uncomfortable by contemporary standards, though, it was emotionally comprehensible. You knew who and where you were. There was little or no mobility physically or socially, so its absence was not missed. There wasn’t much to aspire to or to envy.

Nostalgia, as we know it, didn’t exist. There was no simpler time, no imaginary golden age to look back upon. Around the fires, they wistfully told tales of King Arthur and Robin Hood.

If you’d like to imagine what life was really like, visit Cosmeston Medieval Village in the Vale of Glamorgan, Wales. It is living history in a recreated village of 1350. Built on the foundations of the original hamlet that disappeared centuries ago, Cosmeston was rediscovered during archaeological digs in the 1980s. Historians speculate that the majority of villagers may have died during the plague outbreaks of the 14th century. There’s not much to be nostalgic about.

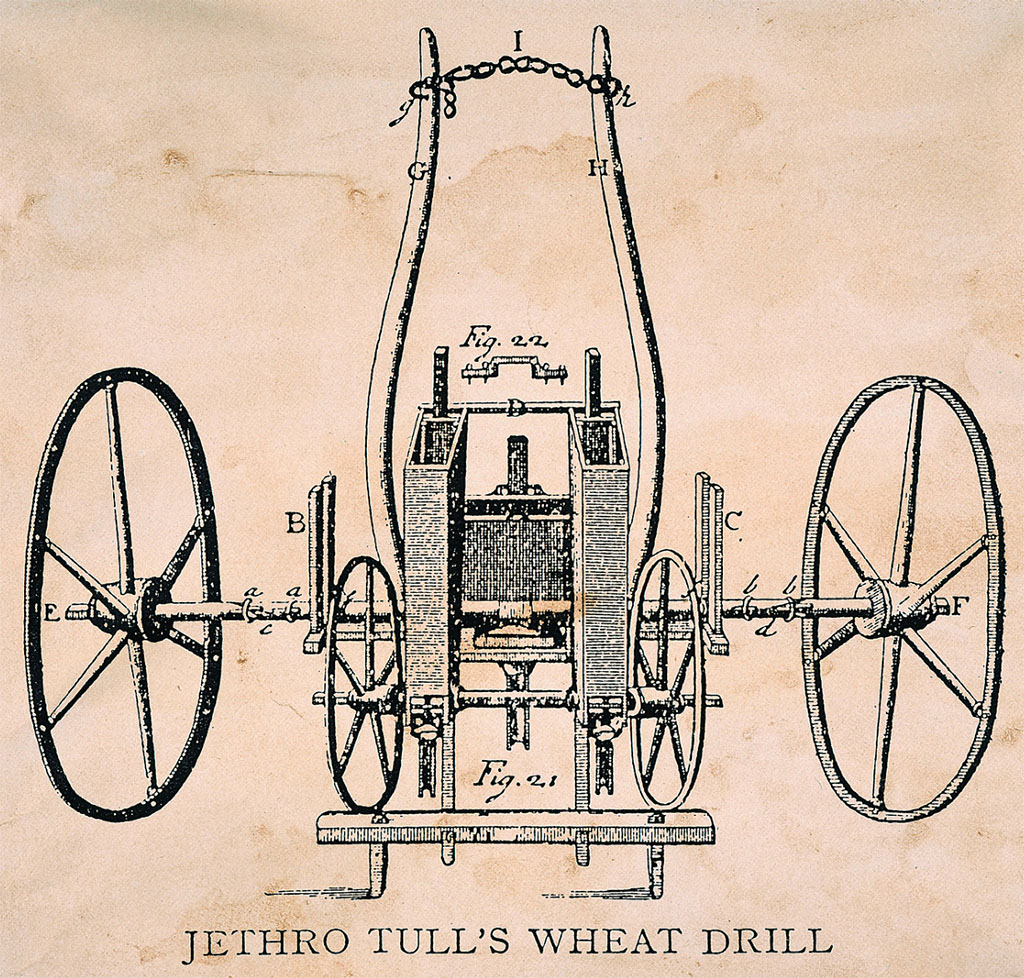

THEN ALONG came mechanization and life changed forever. On the one hand, new machines and tools applied to agriculture meant that fewer laborers were needed to work the land. Thomas Hardy famously tells the story with wonderful poignancy in The Mayor of Casterbridge. Jethro Tull’s seed drill was far more efficient than men walking the fields broadcasting by hand. Mechanical threshing could do the job of many sweaty backs.

[caption id="NostalgiaIsntWhatItUsedToBe_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

BRITAINONVIEW/DAVID NOTON

On the other hand, textile and ceramic goods that were heretofore unknown were manufactured and became available. But they required both ready money to purchase and laborers to produce them. Thus arose the “dark, satanic mills” of William Blake’s Jerusalem. And the laborers, made redundant from the land where they had been eking out an existence for generations, migrated to the mill towns and the nascent industrial cities. Amazing as it sounds today, 12 hours’ daily toil in an often dangerous and ill-ventilated factory was a fair exchange for a cash wage, an increased standard of living and a chance for laborers to acquire even a few of these miraculous goods unknown to their grandparents.

[caption id="NostalgiaIsntWhatItUsedToBe_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

THE GRANGER COLLECTION, NEW YORK

Change, upward aspiration and nostalgia were born. Village life, as such, began its long demise. We have been nostalgic about it ever since.

If we fast forward a few generations, we find a world where the increased pace of change is the only constant. My own quasi-grown children do not remember a world without microwave ovens, mobile phones, easy international air travel or personal computers. When they get to be, say, 60, I wonder what they will be nostalgic for.

A DECADE AGO, I was traveling through the Rhondda on a Sunday morning. American travelers don’t often venture into the old coal valleys of South Wales—just about an hour’s drive west of the Cotswolds. I met an old man on the streets of Ynysybwl who was very curious to get into conversation with the first American he’d seen since “the war.”

I stopped in Trealaw to photograph kids happily engaged on a tarmac playground. They were eager to line up to have their pictures taken. The recognized spokesperson for their group was a 10-year-old girl—the Alpha in an American’s company because she “had been to Cardiff”—some 20 miles to the south. London was no more real to them than it would be to a group of kids in rural Kansas.

The valleys are still often what we might call a “deprived” area. Some 20 years on, they continue to suffer from the closure of the pits and the resulting unemployment. For mile after mile above Pontypridd there is no “other side of the tracks.” Tens of thousands live in towns of two-room-up-two-room-down stone terraced housing—where coal miners raised families and women died young from overwork.

A few years later I took a dear English friend into the Rhondda—a gent in his late 80s, who had grown up in Stockport right after World War I. He didn’t see the area as deprived or poor at all. He’d foraged for coal beside the rail tracks as a boy in Stockport and remembered taking a jam butty home from school under his shirt to share with his mother. These folk in the Welsh valleys had television antennas and cars on the street. They weren’t poor.

I am afraid it’s those television antennas. In the tritely true “rapidly changing world of today,” those televisions bring us image after image of what we do not have, what we should be aspiring to have, where we should want to be going, and, worst of all, what chattels others have that we have not.

Today’s Britain, much more so than the United States, is in the emotionally confused state of having aspiration and nostalgia at war within.

Yes, the quaint local customs, traditions and events often do survive—Padstow’s Obby Oss, Ashbourne’s annual Shrovetide football melee, cheese rolling, pancake races, fetes, unusual festivities and odd games. We can admit that they have long ceased being intrinsically important to people’s lives; they are camp events—a bit of a lark, a bit of a local holiday, a bit of a chance to draw visitors and the pounds they might spend in local shops and pubs. It is all nostalgia in action. All these colorful events do contribute to social cohesion, however, and connect people with their past. We would surely be the poorer for their absence.

‘And what about that pretty thatched cottage with the mullioned windows and the front garden? It is expensive’

WE THINK OF RURAL, village life as being relatively inexpensive compared to living in a market town or urban center. In fact, though, village life is actually more expensive—especially for anyone driving a car in Britain today. The fewer accouterments of life that are close at hand, the more you have to drive that car. With petrol creeping toward $10 a gallon, village folk across the island are discovering that it costs as much to drive out to pick up a dozen eggs and a loaf of bread at the market as it does to purchase the commodities themselves.

What if they are not driving a car? Great Britain has a network of public transportation that we here in the States can only envy. But it is principally located where the people are, in and between the larger towns and cities. If you happen to live in a village a dozen miles from the nearest market town, taking the local bus over to do a few errands is still an all-day outing. If you are a bored, retired OAP looking for excitement, that’s fine, but most of us do not live that way any more.

And what about that pretty thatched cottage with the mullioned windows and the front garden? It is expensive. The property value crunch that has impacted the American housing market has been sweeping through the British real estate market as well. As in so many cute villages in this country, the urban and suburban wealth of out-of-towners long ago priced the substantive housing beyond the range of local rural families.

As writer Sean McLachlan discovered, too, in our story on thatching this issue (p. 46), a thatched cottage is no longer the housing of the simple folk. That roof has to be attended to and insured.

With those village schools closed, too, parents generally have to drive their kids to school. There is no uniform network of public school buses in Britain to ferry students to whatever the nearest appropriate school might be. In the British education system, as well, students quite often do not attend what would be the geographically closest of schools. That petrol gauge just continues its free fall.

The truth is that while many of us are nostalgic for the pretty English village of Miss Marple and a tea shop, colorful cottage gardens, a friendly vicar and the pub, most of us would not choose what’s left of that way of life today. Now that I think about it, having to get in my car to drive out of the village for a pint doesn’t sound so appealing, either.

No, we can’t go back to a simpler time, and most of us really would not want to. Nostalgia isn’t what it used to be. We certainly don’t want to live like folk did when the village was the way of life for a majority of the British people. Life may have been simple, but it was famously nasty, brutish and short. Besides, virtually all of society today takes for granted consumer goods, disposable income and holidays that their grandparents couldn’t have imagined possible.

In any event, the past is to be visited, not lived in. Britain has a past lovingly well-preserved and well-presented to visitors both local and international. Despite everything, as you see, those pretty villages are still there, and have a complex story to tell. It is British Heritage’s delight to bring the isle’s past and present together, and we encourage you to visit both with us.

Comments