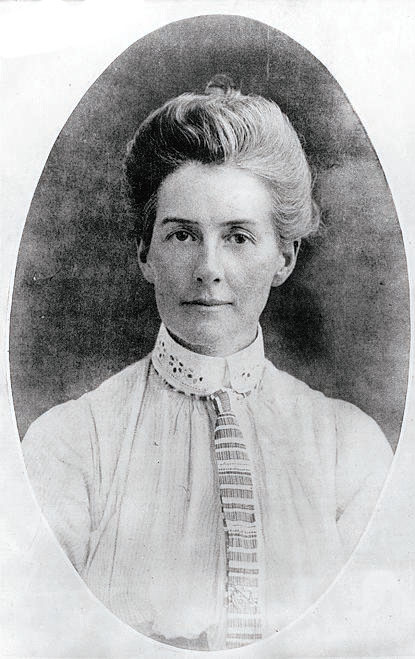

The Execution of Edith Cavell

[caption id="OfCabbages&Kings_img1" align="aligncenter" width="96"]

GREAT BRITISH HEROES – #2

WHEN EDITH CAVELL was growing up in the vicarage in the Norfolk village of Swardeston, little could she have imagined that she was destined to become one of the most powerful symbols of English patriotism in World War I.

[caption id="OfCabbages&Kings_img2" align="aligncenter" width="415"]

THE GRANGER COLLECTION, NY

Both the vicarage where Edith Cavell grew up and the house in which she was born in 1865 still stand in the village some half a dozen miles southwest of Norwich. Her father held the living in Swardeston for 46 years. Edith was raised and educated in the customs of a late Victorian cleric’s family, went off to Brussels as a governess, then trained in nursing at the London Hospital. She was a hospital nurse and by her evident dedication and leadership skills rose to become matron. Fluent in French, in 1907 Cavell was put in charge of a pioneer nursing school in Brussels, providing nurses for several hospitals and dozens of schools.

When World War I broke out, her clinic and school became a Red Cross hospital. After Brussels fell to the Germans, 60 English nurses were sent home, but Edith Cavell remained. As the German army advanced, many retreating British and French soldiers were cut off behind German lines. In the autumn of 1914, Cavell began sheltering stranded British soldiers, spiriting them out of the country to neutral Holland. A small underground cell developed that allowed some 200 Allied soldiers to escape over the following months. The next summer, a Belgian collaborator tipped off the Germans of the clandestine operation. With several others of the escape team, Cavell was interned by the Germans.

At her military trial, Cavell freely admitted that she “successfully conducted Allied soldiers to the enemy of the German people.” Her death sentence by firing squad was carried out hurriedly and stealthily on October 12, 1915, despite the fervent intervention attempt by both U.S. and Spanish authorities. Cavell was hastily buried there at the rifle range where she was shot. Nurse Cavell became a martyr figure; military enlistment in Britain doubled in the eight weeks following news of her death. The huge international outcry following her execution swayed neutral opinion everywhere against Germany and eventually helped bring the United States into the war.

When the war was over, Edith Cavell’s body was returned to England. Following a memorial service in Westminster Abbey, a special train conveyed her remains to Norwich. She was buried at a spot called Life’s Green in the close of Norwich Cathedral. A graveside service is held annually on the Saturday nearest the date of her death.

[caption id="OfCabbages&Kings_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JEREMY HOARE/ALAMY

Across from London’s National Portrait Gallery, where Charing Cross Road rises north out of Trafalgar Square, a statue of Edith Cavell remembers her. Its inscription echoes her words before facing the firing squad: “Standing as I do in view of God and eternity, I realize that patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.”

Many thanks to Billie Scarborough Loshbaugh of Tulsa, Okla., for the nomination of Edith Cavell.

Let your voice be heard. Send along a card or e-mail with your suggestions for “Great British Heroes.” Our e-mail address is [email protected].

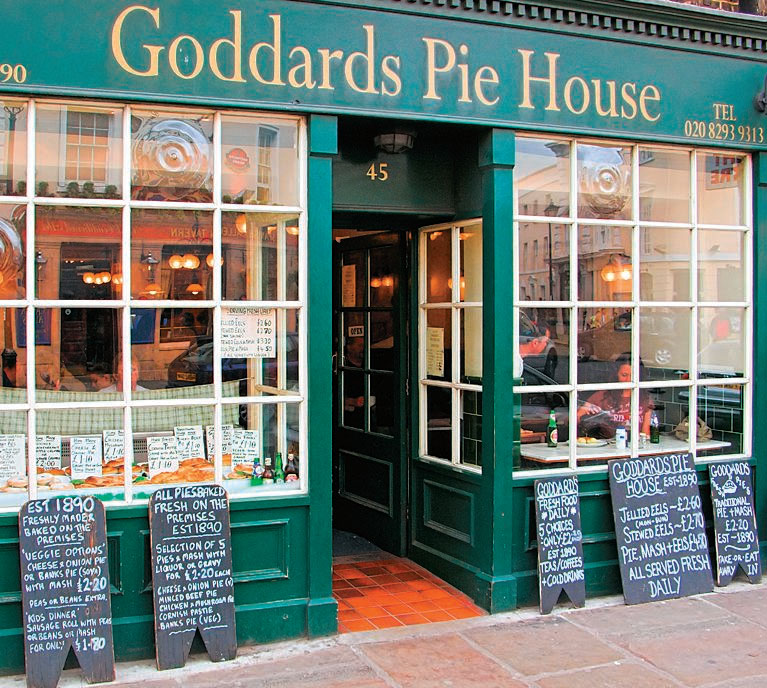

A LONDONER’S PIE HOUSES

Eels, spiced or stewed, whelks pickled, periwinkles, oysters, hot potatoes, muffins, gingerbread and seasonal fruit pies. In the 18th century this was the food of the common man in London, served up by a traveling “hot pieman” who carried a small portable oven. As time passed, better cuts of beef became affordable and the meat pie was born. A large barrow was taken through the streets where the costermonger’s cry was, “Cockles, mussels, eels and hot pies, come and get ’em!”

Born into a Cockney family, I was introduced to this food in 1937. It was natural on Sundays to wait for the sounds of the wheels rolling down my street. With a few pennies in my hand, I would request an order of “Winkles, please gov.”

[caption id="OfCabbages&Kings_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

© PETER FORSBERG/ALAMY

As I grew and ventured around the London neighborhood, it was the pie houses that became my favorite source of food. Like fishmongers, piemen became more prosperous. Pie houses, with clean tiles on their walls and plain tables and chairs, became popular. People would queue up outside for a flakey hot meat pie and potatoes with a choice of liquor (parsley gravy).

[caption id="OfCabbages&Kings_img5" align="aligncenter" width="767"]

CEPHAS PICTURE LIBRARY/ALAMY

The Pearly Kings and Queens were always at my pie house for a meal before heading to my dad’s favorite pub. We felt a part of these people who helped each other and were true to their family and friends.

Today, on my trips home to London it is a must to visit my favorite pie house, at 314 Portobello Road. Owner Ruth Phillips still turns out the great traditional recipes. Actually, when I go to London I attempt to eat at as many pie houses as I can. They still welcome you as friendly as they did in the old days.

Elizabeth Marrin

Auburn, Calif.

CHRISTMAS, IN A PICKWICKIAN SENSE

Understandably and invariably, people tend to associate Charles Dickens with the Christmas season because of his famous story “A Christmas Carol.” Our celebration of Dickens as an inventor of the Victorian Christmas we know and love, however, has many expressions beyond Scrooge and Tiny Tim. Here is Christmas with Mr. Pickwick, from the first novel Dickens wrote, The Pickwick Papers.

As brisk as bees, if not altogether as light as fairies, did the four Pickwickians assemble on the morning of the twenty-second day of December, in the year of grace in which these, their faithfully-recorded adventures, were undertaken and accomplished. Christmas was close at hand, in all his bluff and hearty honesty; it was the season of hospitality, merriment, and open-heartedness; the old year was preparing, like an ancient philosopher, to call his friends around him, and amidst the sound of feasting and revelry to pass gently and calmly away. Gay and merry was the time; and right gay and merry were at least four of the numerous hearts that were gladdened by its coming.

And numerous indeed are the hearts to which Christmas brings a brief season of happiness and enjoyment. How many families, whose members have been dispersed and scattered far and wide, in the restless struggles of life, are then reunited, and meet once again in that happy state of companionship and mutual goodwill, which is a source of such pure and unalloyed delight; and one so incompatible with the cares and sorrows of the world, that the religious belief of the most civilised nations, and the rude traditions of the roughest savages, alike number it among the first joys of a future condition of existence, provided for the blessed and happy! How many old recollections, and how many dormant sympathies, does Christmas time awaken!

We write these words now, many miles distant from the spot at which, year after year, we met on that day, a merry and joyous circle. Many of the hearts that throbbed so gaily then, have ceased to beat; many of the looks that shone so brightly then, have ceased to glow; the hands we grasped, have grown cold; the eyes we sought, have hid their lustre in the grave; and yet the old house, the room, the merry voices and smiling faces, the jest, the laugh, the most minute and trivial circumstances connected with those happy meetings, crowd upon our mind at each recurrence of the season, as if the last assemblage had been but yesterday! Happy, happy Christmas, that can win us back to the delusions of our childish days; that can recall to the old man the pleasures of his youth; that can transport the sailor and the traveller, thousands of miles away, back to his own fireside and his quiet home!

Comments