An 8th-century stroll through the Welsh Marches

[caption id="OffasDyke&Hike_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

COURTESY OF POWY’S COUNTY COUNCIL

LAST WINTER, I FOLLOWED OFFA’S DYKE PATH across the airy 1,300-foot heights of Hergest Ridge that straddles Herefordshire and Powys. Exhilarating gusts of wind giddied my progress into a sideways crab walk, while panoramic views of the Black Mountains and Brecon Beacons spun about.

Latterly, in bright summer sunshine, I tripped along a more southerly stretch of the path through gentle farmland and wooded hillsides, to emerge at the Kymin: 18th-century pleasure grounds bizarrely crowned by a naval temple and castellated Round House, where a Georgian gentlemen’s club dined and enjoyed views over Monmouth. Take a peek inside (it’s now in the care of the National Trust) before descending into town—the birthplace of King Henry V, hero of Agincourt 1415, is perfect for a few hours’ dawdle around museum, inns and 700-year-old fortified gatehouse.

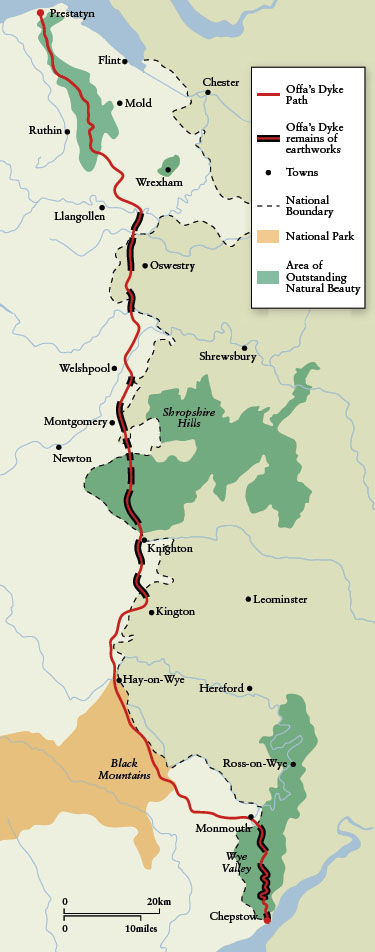

Two days, two completely different experiences. And that’s the magic of the 177-mile Offa’s Dyke Path National Trail, which celebrated its 40th anniversary this year. Running from Sedbury Cliffs near Chepstow on the banks of the Severn estuary, through Welsh border country to Prestatyn and the Irish Sea on the north Wales seaside, the path links the most diverse landscapes of hills, moors, valleys and coast, as well as historic frontier towns and attractions.

Crossing the Wales-England border more than 20 times, striding through eight different counties, three Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty and one National Park, the trail can be walked in 12 days if you have the legs; it’s rumored some crazy folk have nailed it in four. Rob Dingle, Offa’s Dyke Path National Trail Officer, reveals that about 3,000 “end to enders” tramp the whole route each year. Far more people holiday along it in stages, or dip on and off the trail following numerous circular walks of a day’s or half day’s duration.

Of course, the inspiration for the trail is Offa’s Dyke itself, built in the late 8th century by King Offa, ruler of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia. A massive bank with a western ditch, the dyke creates an imposing west-facing earthen wall rising in places to 25 feet. Bishop Asser, writing about a century after its construction, famously described it as leaping “from sea to sea”; today, around 80 miles of it survive. It’s Britain’s longest ancient monument and the greatest example of the Anglo-Saxon dyke-building tradition.

The Offa’s Dyke Path shadows the earthwork for about 60 miles, roughly from Sedbury to Lower Redbrook, and then along stretches from Rushock Hill (north of Kington) to Chirk before parting company as the trail heads into the Clwydian Range Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and the dyke heads for urban Wrexham and to Treuddyn.

Yet the conundrum remains: why did Offa build a dyke? Was it purely a defensive barrier? The King of Mercia (757–796) ruled a territory centered on the modern day Midlands and ruthlessly expanded his influence through conquest, politics and marrying his daughters to other Anglo-Saxon tribal kings. His pre-eminence in what became England was recognised even by the mighty Emperor Charlemagne.

Ian Bapty, archaeologist and honorary secretary of the Offa’s Dyke Association, says: “I’m sure the dyke had a big political purpose, sorting out relations between Mercia and the British living in what is now Wales. But it was also a statement of power and status to the peoples on either side, a huge civil engineering project that showed what Offa could do. And it was a statement to Charlemagne, who was building his empire.”

Bapty surmises that digging and building, using hand tools, sweat and grunt, could have taken two years, drawing on labor from the Mercian heartlands as well as locals. Whether skirting the Wye Valley, exploiting the contours and ridges of the Clun area of Shropshire, or galloping across the lowlands east of Montgomery, the dyke fits and defies nature’s topography.

[caption id="OffasDyke&Hike_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

No archaeological evidence has been found to suggest there were palisades or forts on top of the earthwork, but it seems the western side of the bank—facing the native British—could have been revetted with turf to create a near-vertical aspect. Hence the dyke commanded views into Wales while interrupting key Welsh views into England.

[caption id="OffasDyke&Hike_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

PICTURES: SIÂN ELLIS

After Offa’s death in 796, Mercian power would wane, but his dyke remained and (in the words of the recent application for World Heritage Site status) “exerted a lasting influence on the way the people living around it came to define their cultural identity. This indelible English line on the landscape contributed to a new sense of common unity among the British peoples to the west—the Welsh.”

And so Welsh princes battled with subsequent Anglo-Saxon warriors, and invading Normans studded the Marches (borderlands) with castles. Later, the Welsh would hang any Englishman found on the western side of the dyke, while the English cut off the ears of Welsh trespassers to the east. Even now, though only small parts of the dyke mark the modern boundary between the two countries, “the other side of Offa’s Dyke” is shorthand for England or Wales (depending on the standpoint of the speaker). The potency of the earthwork is etched in the collective psyche; skirmishes and forts have written history in blood and stone along its length.

So, where to find the “best bits” of this path through border heritage? While farming and other incursions have eroded the dyke in many places, sections across the hills from Knighton to the Clun Valley, notably Llanfair Hill, are among the best preserved. Early morning, with the sun casting shadows to throw the dyke into relief, is a good time to capture its snaking essence.

The Welsh name for Knighton, Tref-y-Clawdd, means Town on the Dyke, and it is the mid-point of the trail: a huddle of winding streets and half-timbered houses. Here you will find the Offa’s Dyke Centre, which features displays about the earthwork, the Mercians and Welsh princes, and tourist information, maps and guides are available. There’s also a chunk of the dyke visible in the park, if you don’t fancy heading out of town!

Jim Saunders, Offa’s Dyke Association press officer, told me that the center is licensed for weddings and that occasionally walkers interrupt their rambles to tie the knot here. Until the mid-1800s husbands could obtain a divorce by “selling the wife” on the site where the town clock tower now stands.

In its lower stretches, Offa’s Dyke Path provides iconic viewpoints plus further substantial remains of dyke. The official start point is Sedbury, but many walkers begin at nearby Chepstow and enjoy vistas of the Norman castle overlooking the River Wye, churned a milk-chocolate color here by a tidal rise of some 49 feet. I met a member of the Chepstow Harriers, a local team planning a relay run along the dyke path to celebrate its 40th anniversary, and was told that to complete the trail “properly” you had to dip a foot in the Severn at Sedbury and the other foot in the Irish Sea at Prestatyn.

The Chepstow to Monmouth route via the romantic Lower Wye Valley (and including surprising Kymin) is around 16.5 miles. There’s a breathtaking prospect at Broadrock and Wintour’s Leap, where it’s claimed Sir John Wintour, a local Royalist commander in the Civil War, escaped Roundhead pursuers by galloping his horse off the 200 foot cliff and over the loop of the Wye below. Further along is Devil’s Pulpit, a column of rock on the edge of wooded cliffs from which Satan tried to distract the monks of Tintern Abbey in the valley. Another great place for a picture post-card shot. (The dyke is notable along this stretch, although footpath diversions are in place to help preserve it.)

Following Offa’s Dyke

[caption id="OffasDyke&Hike_img3" align="aligncenter" width="375"]

COURTESY OF POWYS COUNTY COUNCIL

Pandy to Hay-on-Wye crosses the stark uplands of the buzzard-hunted Black Mountains and introduces the trail’s highest point, Hatterrall Ridge (2,300 ft.), and Hay Bluff (2,221 ft.), from which you’ll likely see hanggliders jumping into thin air. The fainthearted can recover by spending a day with noses in books in the celebrated second-hand shops of Hay.

Up country at Llanymynech (where the Wales-England border hacks down the middle of the street), you pass Wales’ largest hill fort, reputedly where Caractacus, chief of the Catuvellauni, fought his last battle with the Romans. And at Chirk Castle the dyke runs through the estate (reached by kind permission in summer only); the medieval fortress, much gentrified, is definitely worth a visit.

The towpath route across Thomas Telford’s 200-year-old Froncysyllte Aqueduct that carries the Llangollen Canal 116 feet above the River Dee is a World Heritage Site “must see,” with peerless views over the tree-lined gorge. Regain your breath in Llangollen and maybe visit Plas Newydd, home of the famous eccentric Ladies of Llangollen.

For wild atmosphere the Eglwyseg Crags and, later, the trek through the Clwydian Range, past evocative earthwork forts and with gazes to Snowdonia, are wonderful. The path passes close to Rhuddlan, where Offa died in battle against the Welsh in 796.

After all that, arrival in modern, seaside Prestatyn is a considerable come-down from ancient history. But a chilly toe-dip in the Irish Sea should perk you up.

What’s on Offa?

Access

Stretches of Offa’s Dyke Path are within reach of many towns: Monmouth, Llangollen and Prestatyn are on the trail. Or visit from Bristol (18 miles), Ludlow (15 miles), Shrewsbury (16 miles), Hereford (16 miles), Chester (20 miles).

Travel

There are railway stations at Chepstow (one mile from the trail), Knighton and Prestatyn. But getting there by car is easiest.

Walking

If you aren’t minded to become an “end to ender”, there are numerous short, circular walks that incorporate parts of Offa’s Dyke Path. There are also luggage transfer services, so you don’t have to lug everything with you if you’re rambling a chosen stretch for a few days (see below).

The Shropshire Hills Area of Natural Beauty has developed “Walking With Offa,” a dozen scenic walking routes of several miles designed to take walkers from one quaint country pub to another. What’s not to like? www.shropshirehillsaonb.co.uk

Further information

For route information, details of accommodation, inns, trains/buses, distance calculators, guides and luggage transfer, visit Offa’s Dyke Path National Trail www.nationaltrail.org.uk/offasdyke and Offa’s Dyke Association www.offasdyke.demon.co.uk.

[caption id="OffasDyke&Hike_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

[caption id="OffasDyke&Hike_img5" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

PICTURES BY SIÂN ELLIS

Comments