Bits of Books About Britain

[caption id="OntheBookshelf_img1" align="aligncenter" width="127"]

LAST ISSUE, WE WRAPPED UP our series on the 10 most British books of all time with John Galsworthy’s popular The Forsyte Saga. To count them down again, our fan favorites as the most British of books are:

10. The Mayor of Casterbridge by Thomas Hardy

9. Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh

8. Alice-in-Wonderland by Lewis Carrol

7. Ivanhoe by Sir Walter Scott

6. Winnie-the-Pooh by A.A. Milne

5. The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer

4. Tom Jones by Henry Fielding

3. Middlemarch by George Eliot

2. Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

1. The Forsyte Saga by John

What a wonderful cross-section of British life is here represented, from the Wife of Bath to Lord Sebastian, Elizabeth Bennett to Piglet, Robin Hood and Michael Henchard to Irene Forsyte. A number of folk, however, have mentioned the absence of Charles Dickens from the list. In truth, votes for Dickens were split between so many of his evocative novels of Victorian England that no single title stood out. No, we can’t forget Dickens. In the season when we recall Dickens the most, then, let’s look at the novel that made him famous.

[caption id="OntheBookshelf_img2" align="alignright" width="302"]

Happy, happy Christmas, that can win us back to the delusions of our childish days; that can recall to the old man the pleasures of his youth; that can transport the sailor and the traveller, thousands of miles away, back to his own fireside and his quiet home!

YES, MERRIE OLDE ENGLAND. Thatched cottages and wayside inns, hedgerows and horses, beer and voluptuous gardens, leather smells and portly, ruddy-cheeked eccentrics—like Mr. Pickwick. The merrie olde England of our imaginations has always been a temps perdu, created largely by the fancy of Charles Dickens. Everyone today knows Dickens as the inspiration for our images of a Victorian Christmas (through “A Christmas Carol,” of course). More broadly, however, I think Dickens is likely the biggest single influence upon our imaginative construct of Victorian England.

Later in his prolific writing career, Dickens turned to the darker themes of Victorian life: the bleakness of working poverty, the plight of unprotected children, the arcane carelessness of the law and more. David Copperfield, Hard Times, Great Expectations and Bleak House seer into our minds a picture of 19th-century life’s pitfalls and injustices. The novel that made Charles Dickens a multimedia megastar in his own time, however, portrays a very different England indeed.Later in his prolific writing career, Dickens turned to the darker themes of Victorian life: the bleakness of working poverty, the plight of unprotected children, the arcane carelessness of the law and more. David Copperfield, Hard Times, Great Expectations and Bleak House seer into our minds a picture of 19th-century life’s pitfalls and injustices. The novel that made Charles Dickens a multimedia megastar in his own time, however, portrays a very different England indeed.

Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers is a rollicking, comic epic, recording the transactions of The Corresponding Society of the Pickwick Club, under the benign and kindly direction of Samuel Pickwick, Esq. G.C.M.P.C. (General Chairman—Member Pickwick Club). A rotund, jolly amateur scientist and part-time humbug, Pickwick is joined by three companions, Winkle, Snodgrass and Tupman, who fancy themselves respectively, if unimpressively, a sportsman, a poet and a lover. Charged with reporting back to the broader membership of the Pickwick Club, the amiable corresponding committee sets about on a seemingly directionless quest seeking something worth reporting.

This is a classic literary example of innocence in search of experience. Self-content and self-deluded, the four friends each think of themselves as more accomplished, worldly and wiser than they are. Over port in the clubroom, such bravado is a harmless, collective delusion. In the real world, however, it takes the young street-smart Cockney, Sam Weller, as general factotum to Mr. Pickwick, to buffer them all from the slings and arrows of outrageous reality.

Together, the well-meaning and gentlemanly Pickwickians (and Sam) ramble across early Victorian London and rattle afield in stagecoaches to such far-flung destinations as Bristol, Birmingham and Bury St. Edmunds. With great conviviality and perpetual optimism, the quartet engages in the adventures of life across the social spectrum of 19th-century England. Peppering the narrative with comic characters and caricatures, Dickens tosses our heroes into politics and parties, villages and villains, romantic liaisons and an assortment of trivial calamities—set against a backdrop of quadrilles, Christmas parties, cheerful inebriates, flirting widows, smoky coffee rooms, idiosyncratic tradesmen and frosty winter mornings. This is the merrie olde England we know and love.

The novel was published as a periodical, in 19 monthly installments during 1836-37. The early numbers had press runs of 500 copies. By the story’s completion in November 1837, however, its circulation was 40,000 and copies appeared throughout the English-speaking world. Pickwick became a phenomenon, and so did Charles Dickens. In perhaps the original prototype of crossover marketing, there were Pickwick china figurines and fabric, hats and canes, songs, cigars and sequels. On the heels of Pickwickian success, Dickens similarly wrote and published Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby and The Old Curiosity Shop in quick succession. Pickwickian was a word well understood by the public of the 1840s, and so was “Dickensian.”

To see these reviews and hundreds more by leading authorities, go to our new book review section at www.historynet.com/reviews

HISTORYNET.COM

FROM THE WORLD’s LARGEST HISTORY MAGAZINE PUBLISHER

In 14 major novels and sundry stories and writing collections, Dickens left a literary legacy that described the life of his age like no other. His portrayals of industrial squalor, a labyrinthine legal system and the failed humanity and exigencies of Victorian life remain iconic in their power to this day. The youthful exuberance and light-hearted voice of The Pickwick Papers is unique in Dickens’ canon. Had it been the only novel he had written, however, the transactions of the Corresponding Society might well have been voted the most English book of all time at least.

DANA HUNTLEY

[caption id="OntheBookshelf_img3" align="alignright" width="721"]

KUNSTHAUS, ZURICH

AS AN ART HISTORY GRADUATE, I have long considered London’s Royal Academy of Arts to be a favorite haunt of mine. Housed in 19th-century Burlington House, just off Piccadilly, the RA has an exhibition calendar that never ceases to excite and a venue that provides a dramatic West End rival to the National Gallery and both Tates. The RA is unique in that it is completely self-governing and receives absolutely no state funding. This is surprising to many, but it enables the institution an intrinsic freedom and direction that many museums and galleries are denied. This autumn, the RA really hit the mark and co-curated the first major retrospective in 20 years of the prolific French sculptor, Auguste Rodin (1840-1917).

Iconic works such as The Gates of Hell, The Thinker, The Burghers of Calais and The Kiss feature alongside monuments to Victor Hugo and James McNeill Whistler. These are juxtaposed with 200 exceptional works that are on loan from both the Museé Rodin and Rodin’s home at Meudon.

As a sculptor, Rodin heralded the modern age, breaking with both tradition and classical sculpting methods. He would fluidly model clay representations of moving models, from which a plaster copy would be taken and, after much experimentation, casts made. The evolution of these sculptural techniques are explored by hanging paper studies close to preliminary models.

The exhibition considers ten chronological themes that reveal Rodin’s inspirations—his studies of relaxed and unposed models to his fascination with antiquities. Rodin was also a talented draftsman, and the show includes many lyrical and erotic drawings alongside photographs of the artist and his work.

The main focus of the exhibition, however, explores Rodin’s relationship with Britain. It was here that he first made his name in the international art world before he gained recognition in Paris. Rodin initially visited London in 1881 and exhibited at the RA the following year. Thanks to the enthusiasm of early collectors such as Lord Leighton (a former president of the RA) and the influential Constantine Ionides, Rodin’s profile grew as did his confidence. The visits and honors were renewed after 1900 when the founding collectors of museums in Cardiff, Manchester and Glasgow bought work. Rodin found himself feted by the aristocracy and politicians who commissioned portraits. This affinity with Britain was further strengthened in 1914, when he bequeathed 18 works to the nation, now owned by the V&A, and included in this show.

The exhibition is quite breathtaking and includes rare opportunity to discover many works that have never been exhibited outside of France before. Rodin at the Royal Academy of Arts is open daily at the Royal Academy, unhappily only until January 1.

LIZZIE MEADOWS

[caption id="OntheBookshelf_img4" align="alignright" width="400"]

Monarchy,with David Starkey, DVD 2-vol. boxed set, Acorn Media, Silver Spring, Md., 317 minutes, $39.99.

COLORFUL BRITISH HISTORIAN and royal authority David Starkey returns to PBS this year with the new six-episode series Monarchy. As he did in his popular series The Six Wives of Henry VIII, Starkey tells the story with panache. This time, however, his subject is more than 1,000 years of the English crown. It is a tale of “Bloodshed, betrayal and glory, straight out of the pages of history,” as the series headline reads.

From historical locations the length and breadth of Britain, Starkey recounts the fortunes and foibles of the monarchy as it developed over the centuries. Taking us from Alfred the Great’s defensive war against the Vikings to the Restoration of Charles II, the series has an ambitious scope indeed. Historical reenactments, ancient documents, dramatic camerawork and Britain’s breathtaking landscapes form a visual backdrop that keeps the viewer engaged and involved in the action.

With only six hourlong episodes to present such a huge tapestry of history, the pace of the series moves at breakneck speed. All history is selective, of course, and Starkey certainly needed to be. There is plenty of significant history missing here. Still, Starkey manages brilliantly to provide an overview of English and early British history that is comprehensible, satisfying and rewarding. If has Monarchy not come around to your PBS station yet, don’t miss it when it does. This is a series that is worth seeing and owning and passing on to your grandchildren.

Briefly Noted:

[caption id="OntheBookshelf_img5" align="alignright" width="388"]

The Man Who Saved Britain: A Personal Journey into the Disturbing World of James Bond, by Simon Winder, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York, 294 pages, hardcover, $24.

AFTER WWII LEFT BRITAIN broken and bankrupt, the dismantling of the British Empire was inevitable. Though Britain had been victorious in war, the victory was costly in every way. In short order, the British people faced the reality that Britain’s prestige and influence around the world largely disappeared with the independence of its colonies. As the Cold War settled across Europe, and life in Britain was still governed by rationing and restrictions, what could possibly help the British to feel good about themselves again? The name is Bond, James Bond.

James Bond was the fictional anodyne to a real-life Britain in the 1950s that was colorless, dispirited and grim. Or so Simon Winder posits. This delightful book is very much Winder’s personal journey. Though the narrative leads down some blind alleys, Winder engagingly takes the reader along with some sparkling writing (reminiscent of P.J. O’Rourke, or Wodehouse writing nonfiction).

In America, of course, Bond is known by the franchise of action movies, not through Ian Fleming’s fanciful novels. Beginning with Casino Royale in 1953, the James Bond novels appeared at roughly yearly intervals until Fleming’s death in 1964. The suave, upper-crust Bond may have been, as Winder describes him, “a non-detoxed Peter Pan figure who never accumulates self-knowledge or fear,” but he was a romantic hero at a time when Britain dearly needed such a figure, real or fictional.

[caption id="OntheBookshelf_img6" align="alignright" width="373"]

Hide-and-Seek With Angels: A Life of J.M. Barrie, by Lisa Chaney, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 402 pages, hardcover, $27.95.

IN THE EARLY DECADES of the 20th century, J.M. Barrie was among the most successful playwrights and novelists in England. Today, he is remembered largely for Peter Pan—the story of the immortal boy who would not grow up. The interplay of fantasy and reality in Barrie’s life and works highlights this new biography of the neglected author.

The Art of Domestic Life: Family Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century England, by Kate Retford, Yale University Press, New Haven, 368 pages, hardcover, $65.

THIS IS NOT A COFFEE-TABLE book, but a lively written, elegantly illustrated introduction into the way painters like Benjamin West, Thomas Gainsborough, Sir Joshua Reynolds, William Hogarth and others communicated so much about their world and way of life in the domestic portraits that were the fashion of the day. Expensive, but excellent.

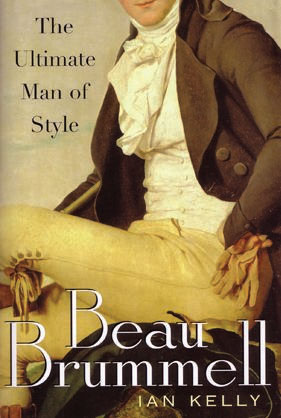

[caption id="OntheBookshelf_img7" align="alignright" width="281"]

Beau Brummell: The Ultimate Man of Style, by Ian Kelly, Free Press, New York, 416 pages, hardcover, $26.

YES, INDEED, THE WORLD’s most famous dandy was a man of style. In the late 18th century he virtually invented modern male dress, including the ubiquitous suit. Ian Kelly’s biography is lively, but serious and sad. After his years as bon vivant and arbiter of taste for London society, Brummell’s life ultimately became a cautionary tale of narcissism and dissolution, as his last decades were spent in exile for debt, dependent upon the generosity of friends and declining steadily deeper into tertiary syphilis and madness.

Landmarks of Britain: The Five Hundred Places That Made Our History, by Clive Aslet, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 540 pages, hardcover, $29.95.

THE PROBLEM WITH LISTS, however colorfully annotated, is that they are subjective. “The 500 places that made our history” sounds so authoritative. How convenient that there happened to be exactly 500 of them. The Lion Salt Works in Marston, Arnos Grove tube station, the Slough Trading Estate, the Reading Young Offenders Centre and Spaghetti Junction all make the cut. This book might be a bit idiosyncratic, but it is rich with well-written anecdotal history and wonderfully illustrated. A great gift book for any devoted Anglophile.

Comments