The Latest Books About Britain

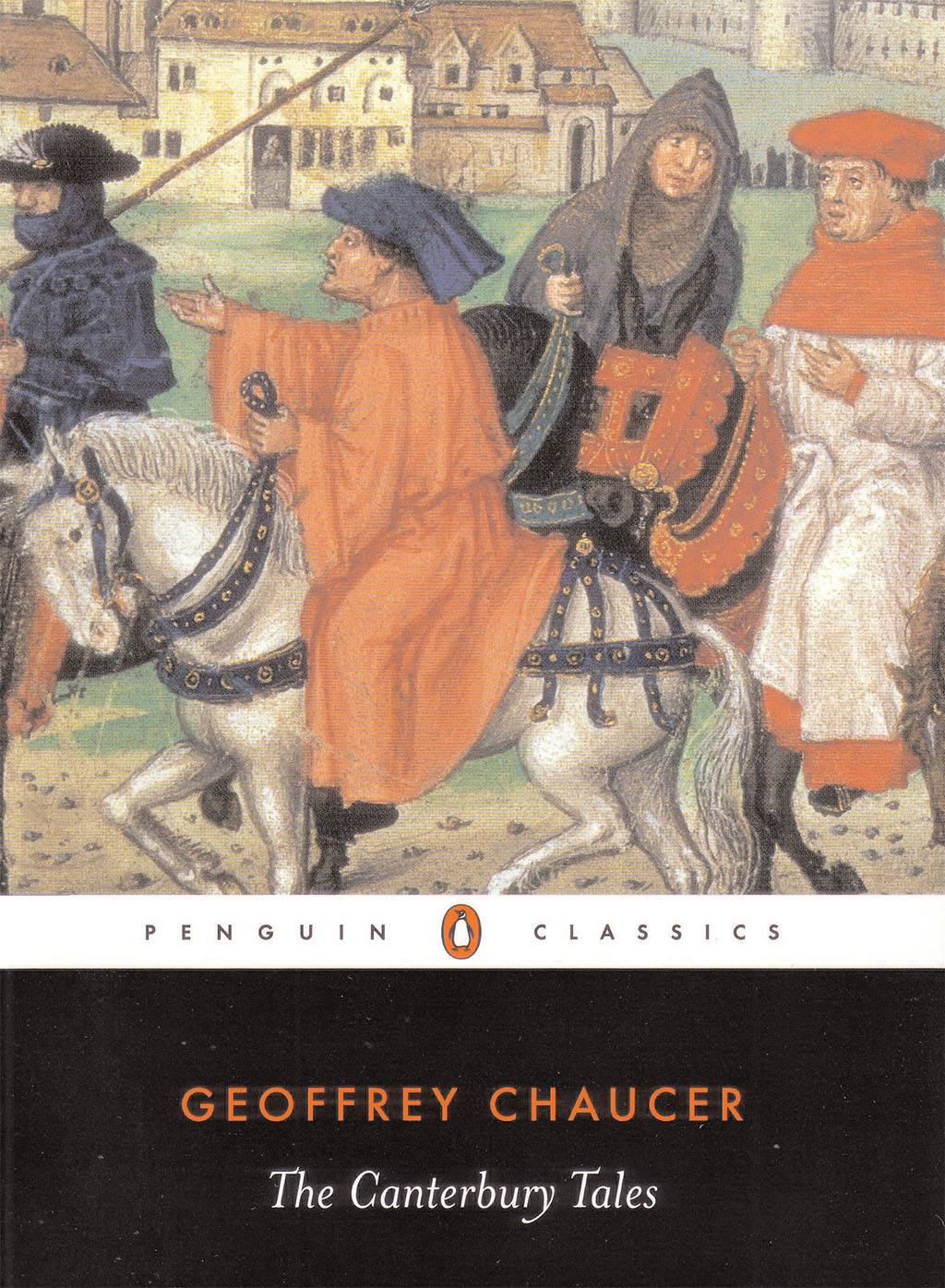

GEOFFREY CHAUCER’S The Canterbury Tales was, quite simply, the first important work of literature to be written in the English language (what we now call “Middle English” though it may be). If for no other reason, perhaps, would Chaucer’s 14th-century verse masterpiece merit inclusion as No. 5 on our list of the 10 most British books. In the process, though, Chaucer provides in his tales and their framework a microcosm of life in England during the late 1300s. This issue, we place Chaucer in the context of his age with a look at Miri Rubin’s very readable late medieval history The Hollow Crown. Then, we are happy to put on the bookshelf veteran BH writer Brenda Lewis’ new photo essay on Winston Churchill. She was putting the finishing touches on the book while recalling for BH her memories as a girl during World War II that we featured in September 2005. Enjoy!

[caption id="OntheBookshelf_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

The Canterbury Tales, by Geoffrey Chaucer. Available in many editions, both soft and hardcover.

HOW DOES ONE visualize medieval England without reference to the gallery of vivid portraits in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales? It is virtually impossible. The Canterbury Tales helped to established English as the language of the nation’s literature, replacing French and Latin. A contemporary of Chaucer described him aptly—and with memorable alliteration—as “the first finder of our fair language.”

Geoffrey Chaucer (circa 1340-1400) was born into a family of wealthy London wine merchants with ties to court, connections that were to be central to his life. For some 35 years, he served the royal family—Edward the Black Prince, John of Gaunt and King Edward III. His eventful military service in France included capture by the French and ransom by the British. Later, the court periodically sent him on diplomatic missions to France and Italy. Perhaps the most significant of the several court offices Chaucer held was that of King Richard II’s clerk of works, a position that made him responsible for the maintenance of royal lodges and palaces, including the vast palace of Westminster.

If more is known of Chaucer’s life than that of other medieval English poets, that information sheds little light on his creation of The Canterbury Tales. In one of his earlier poems, “Troilus and Cressida,” he takes readers into the world of court intrigue, obviously a topic he knew well because of his service to the Crown.

It is very possible that during his diplomatic stays in Italy, Chaucer became acquainted with Boccacio’s Decameron, an early example of the frame-story genre, in which separate tales are told within a unifying story. In Decameron a group of young lords and ladies agree to tell tales while they stay in a country villa, to avoid the plague that is ravaging the cities. Because each of Boccacio’s narrators belongs to the same aristocratic class, the Decameron tales are similar in their sophisticated tone.

Chaucer, however, in The Canterbury Tales, came up with the ingenious literary device of having a pilgrimage, a technique that allowed him to bring together a diverse group of people. Consequently his narrators represent a wide spectrum of English society with various ranks and occupations.

From the high-born, noble knight, the pilgrims descend through the prioress, the clerk, the franklin (a rich landowner), the bawdy wife of Bath, and on down the social scale to the vulgar miller and the corrupt pardoner (a man who sells “pardons” for sins). Not only are the narrators a superb representation of medieval English characters, but also the stories they tell are remarkably varied.

The narrative “frame” of The Canterbury Tales is quite simple. In April, with the beginning of spring (“Whan that Aprill with his shoures sote / The drought of Marche hath perced the rote”), people of varying social classes come from all over England to gather at the Tabard Inn in preparation for a pilgrimage to Canterbury. Interestingly, Chaucer himself is one of the pilgrims.

That evening the host of the Tabard Inn suggests that each member of the group tell a tale on the way to Canterbury to make the time pass more pleasantly. The host decides to accompany the party on its pilgrimage and appoints himself as the judge of the best tale.

It is the knight, the most prominent person on the pilgrimage, the embodiment of truth and honor, who tells the first tale. Predictably, his story highlights chivalry in matters of war and matters of love. Set in ancient Greece, it features the Duke of Theseus and his noble quest for social justice. Unmistakably, Chaucer the pilgrim admires the venerable knight, but, never a snob, his appreciation of the comic miller is equally intense.

All of Chaucer’s characters come alive through dialogue, especially the coarse miller with his licentious tale of a rich old carpenter married to a voluptuous 18-year-old girl. Nowhere is Chaucer’s talent for rendering comic incongruity more apparent than in that telling.

To see these reviews and hundreds more by leading authorities, go to our new book review section at www.thehistorynet.com/reviews

[caption id="OntheBookshelf_img2" align="aligncenter" width="230"]

Since they persistently interrupt and insult each other, it is surprising that more than 20 pilgrims succeed in telling a tale. The fragile bond holding the group together is constantly threatened by quarrels and class enmity. Chaucer excels at portraying the dynamic interactions between the assorted travelers, particularly when he has one character tell a tale designed to show another in a bad light. An example of this is the elderly and irritable reeve’s vicious tale about a dishonest miller. He told it in retaliation for the miller’s tale about a stupid carpenter, and the reeve had once worked as a carpenter.

Despite the dissimilarity of the stories, there is a seamless quality to the work as a whole. The storytellers’ common destination, of course, binds the tales together. (Progress in the journey is mentioned at intervals by reference to place-names.) More important, the tales are also bound together by a cleverly woven central theme: the role of chance in human affairs. Chaucer challenges both the notion that a person controls his/her own destiny and the notion that a divine ruler dispenses happiness in proportion to a human’s merits.

Although his theme is harsh, Chaucer the poet is undeniably a celebrator of life and a lover of mankind. He gave England something that had been lacking since Anglo-Saxon times—creative writing in the vernacular that could bear comparison to anything produced on the Continent.

Even today, some 700 years after its publication, The Canterbury Tales endears itself to readers through its sparkling dialogue, acute rendering of character, sympathetic understanding of humanity and warm humor.

Katherine Bailey

The Hollow Crown: A History of Britain in the Late Middle Ages, by Miri Rubin, Penguin Books, New York, hardcover $16.

[caption id="OntheBookshelf_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

LATE MEDIEVAL BRITAIN is often considered a transitional time, an era wedged uncomfortably between feudalism’s peak years and the rise of the modern age. Many observers focus on the period’s volatility and overall nastiness rather than viewing it as an integrated whole.

Now comes a volume designed to tone up an often undervalued era. Miri Rubin’s The Hollow Crown—the title is taken from a line in Shakespeare’s Richard II—is the latest volume in the Penguin series of British history texts. Professor of medieval history at the University of London, Rubin is nothing if not ambitious in scope. She aims to present an inclusive portrait of the economic, political, ecclesiastic, diplomatic and social factors affecting English life between 1307 and 1485—a crowded pair of centuries on the British historical stage.

The horrors we rightfully associate with the age are all here: the butchery of the off-and-on Hundred Years’ War (which England effectively lost), the Peasants’ Revolt, the War of the Roses, famine and near-continual political conspiracy and death—with five English monarchs deposed and five more dying violently.

Above all else, the Black Death hovers like a ravenous dragon, arriving without warning in 1348 to reduce the population by perhaps as much as half. The survivors were traumatized, but economically better off. A reduced labor force could demand higher wages; farming had to diversify due to the labor shortage. More and better food became available.

Rubin’s main theme is that while England in the late Middle Ages (Scotland and Wales are mentioned only sporadically) was a dangerous place and time to be alive, the era did much to define the nature of Britain. As Rubin demonstrates, the rich social and cultural milieu of the time set the stage for early modern Britain to appear shortly.

Plague, unrest and famine aside, this is also the period that saw the establishment of a distinctively English style of architecture (English Perpendicular). Geoffrey Chaucer wrote the first great English work with The Canterbury Tales; printing appeared; feudalism disappeared. The English language supplanted Norman French as the language of government and would soon blossom with the works of Sidney, Spenser, Shakespeare and Marlow.

The author’s scattergun approach to each of her topics often works, giving the reader a sense of the period as the narrative segues from peasant to prince, monk to manor house, skipping nimbly between the classes and the issues separating them. By trying to cover too much, however, there are times when The Hollow Crown becomes a jumbled mess—like a confused movie with too many jump cuts.

Rubin is most gripping when dealing with the perpetually dicey political situation—the seemingly endless parade of kings, princes and pretenders vying for ultimate power and expanded territory: from the valiant warrior-kings Edward III and Henry V to the ineffectual Richard II and the notorious Richard III.

The volume ends almost inevitably with the 1485 Battle of Bosworth, which saw the death of the last Richard and the crowning of Henry VI, and changed the fiscal and administrative management of the English government decidedly for the better. The new king effectively ushered in the English Renaissance and stabilized the country following terrifically unsettled times. More than a few times The Hollow Crown can be a trial to wade through, but it is well worth the effort.

Paul Nurse

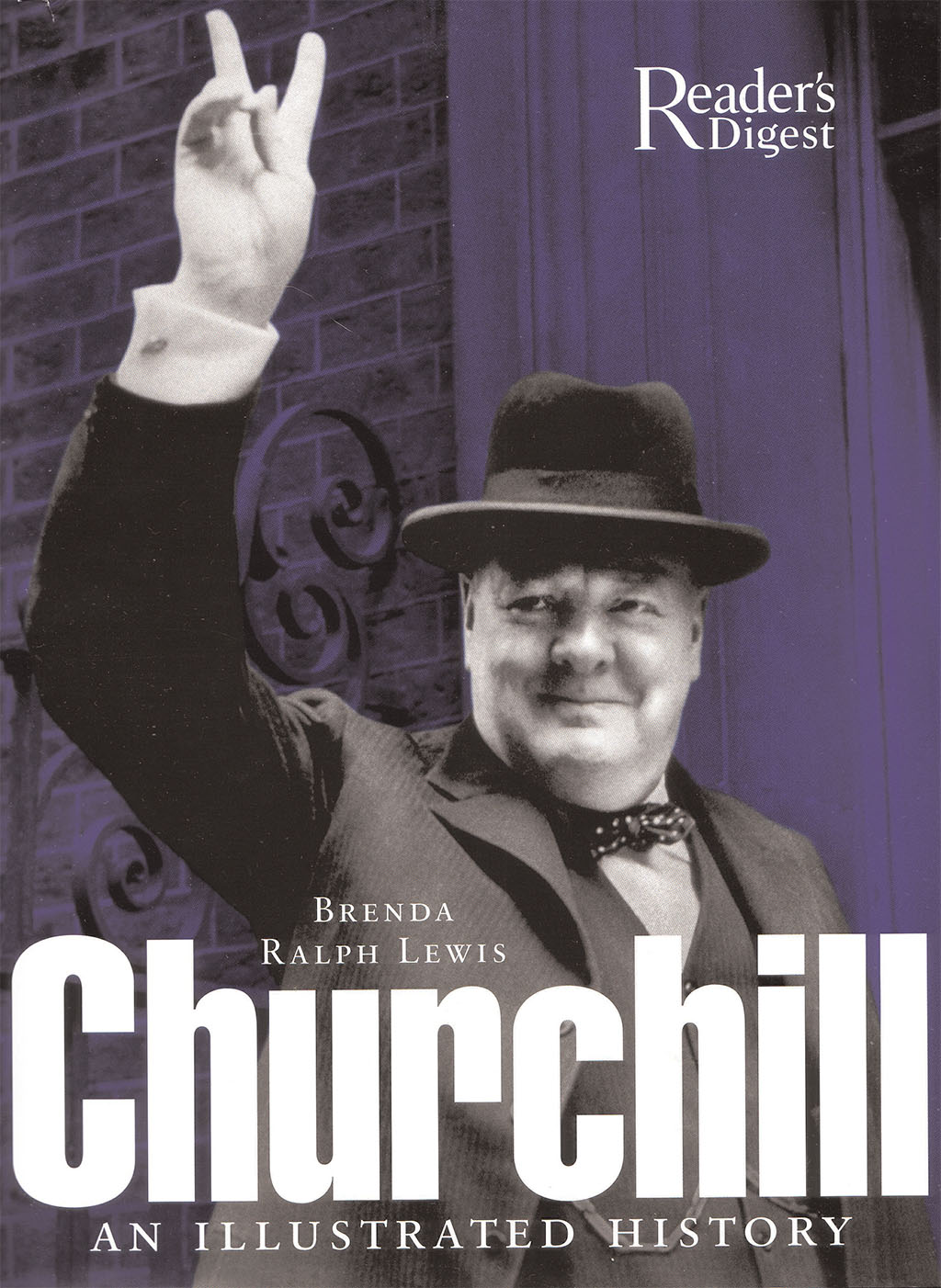

Churchill: An Illustrated History, by Brenda Ralph Lewis, published by Reader’s Digest, New York, 256 pages, hardcover $30.

“WE SHALL FIGHT on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.” Address to Parliament, June 4, 1940.

Soldier, statesman, author and master politician: Yes, Winston Churchill left his mark on the 20th century. Regarded widely as the greatest Briton of all time, it is for Churchill’s bulldog tenacity as wartime prime minister that the English statesman is best known and universally admired. Had he never emerged from his “wilderness years” in the ’30s to lead the wartime Cabinet through Britain’s historic struggle against Nazi Germany, however, Churchill would still deserve his place in history as one of the 20th century’s most remarkable men and insightful politicians.

[caption id="OntheBookshelf_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

When Churchill became prime minister in May 1940, he had already enjoyed a full career in Parliament and in the Cabinet, including turns among other offices as president of the Board of Trade, home secretary, first lord of the Admiralty and chancellor of the Exchequer. He was already old enough and accomplished enough to retire bathed in honors.

After King George VI summoned Churchill to the palace and asked him to form a wartime government, however, the new prime minister wrote, “I felt as if I were walking with destiny, and that all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial.” And the rest, as they say, is history.

In fact, it is a history diligently and copiously recorded. Books about Churchill’s life and career abound. A quick search of Amazon yields 30,288 entries for key words “Winston Churchill.” As it happens, however, longtime British Heritage author Brenda Ralph Lewis (see “Them Foreigners Up from Lunnon,” September 2005) has brought a meaningful addition to the library of material available on Churchill and his times.

Churchill: An Illustrated History is a superb blend of word and image, containing more than 190 rare color and black-and-white photos of Churchill and the many famous people of his acquaintance.

Lewis’ easygoing narrative style unpacks Churchill’s life story with verve and sensitivity. While Churchill’s dramatic and world-changing wartime leadership understandably takes center stage in any profile of the great man’s life (and occupies more than a third of the book), the strength of this biography-that-reads-like-a-story is how Lewis weaves the wartime years into the broader tapestry of Churchill’s life.

This volume is never going to supplant exhaustive Churchill biographies like William Manchester’s The Last Lion. It does, however, offer a vibrant and unusually well-illustrated overview of the man from his swashbuckling days as a war correspondent and cavalry officer to elder statesman on the backbench of Parliament until his death at the age of 90.

It was after Churchill’s tenure as heroic wartime prime minister, when he was in his 70s and 80s, that he won the Nobel Prize for writing the six-volume history The Second World War, not to mention his four-volume masterpiece A History of the English Speaking People. Oh, and by the way, he continued to lead the Conservative Party for another 10 years, returning to become a Cold War prime minister in the crucial years of 1951-55.

It is impossible to imagine what the world would be like today without the enormous influence Churchill exercised upon 20th-century events. When Churchill resigned from office as prime minister in 1955 and left government (though not Parliament) for the last time, his son Randolph wrote to him: “Your glory is enshrined forever on the unperishable plinth of your achievement….It will flow with the centuries.” It’s a modest epitaph. If you’ve any questions, Brenda Lewis’ well-done book explains why.

Dana Huntley

briefly noted:

Her Majesty’s Spymaster: Elizabeth I, Sir Edward Walsingham and the Birth of Modern Espionage, by Stephen Budiansky, Viking, New York, hardcover $24.95.

THIS IS A RIPPING yarn, and a wonderful introduction to the personality of Elizabeth I, her court and her times. As fascinating a character as Walsingham is himself, he melds into the broader picture of late 16th-century England.

Birmingham, by Andy Foster, Yale University Press, New Haven, softcover $25. Leeds, by Susan Wrathmell, Yale University Press, New Haven, softcover $25.

SINCE THE 1950S, the Pevsner Architectural Guides have been an authoritative companion to the historic architecture of Britain. Yale University Press continues the program, publishing revisions and new titles in the series. These recent volumes on Leeds and Birmingham offer a visually beautiful, clearly written introduction to the architecture of two major and often neglected English cities.

The Longest Night: The Bombing of London on May 10, 1941, by Gavin Mortimer, Berkley Caliber, New York, hardcover $24.95.

FOR SEVEN MONTHS the Nazi blitz had rained German bombs on the city of London—all prelude to the night of the Luftwaffe’s most devastating air attack on England’s capital. Though 1,436 civilians died that night and the city was ablaze, one London publican posted a sign outside his damaged premises: “Our windows are gone but our spirits are excellent. Come in and try them.”

Comments