The remains of Rievaulx Abbey, a former Cistercian abbey near Helmsley in the North York Moors National Park, North Yorkshire, EnglandAnthony McCallum / CC

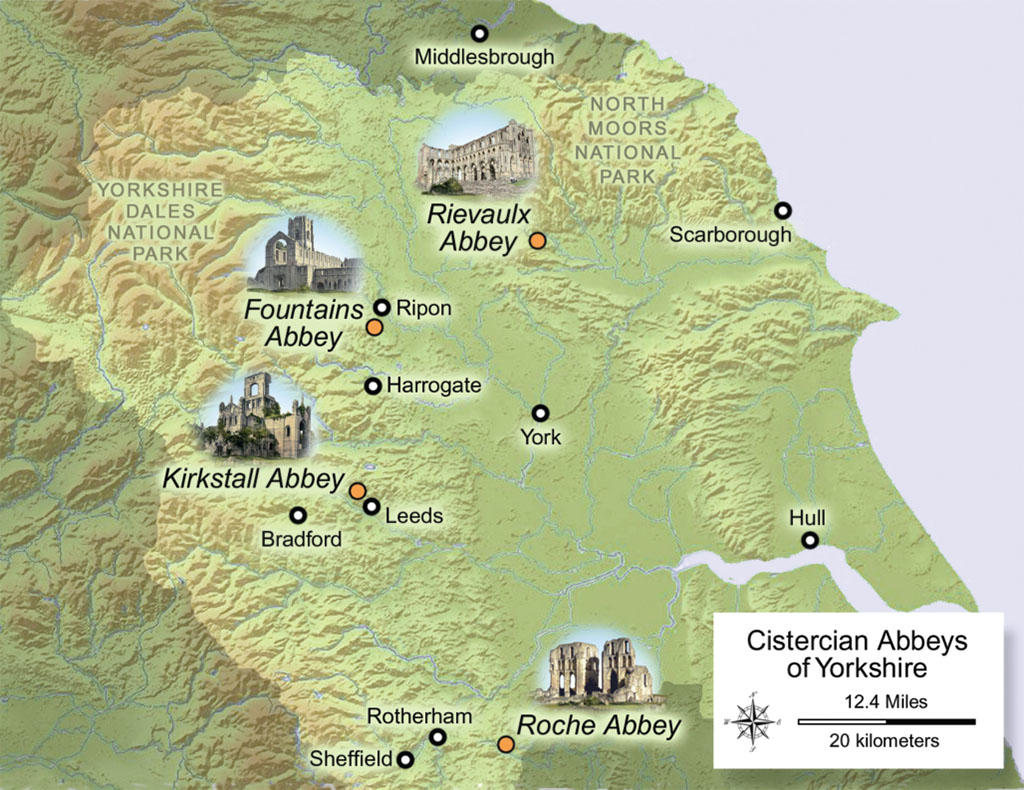

Did you know there are four Cistercian abbeys in Yorkshire, all worth a visit? Take a journey through the rise and fall of the monastic communities of medieval Britain with us.

It took the White Monks a couple of decades to conquer Yorkshire. I reckoned I could do it in a couple of days.

The ruins of four monasteries formerly belonging to the Cistercians are within the boundaries of Yorkshire, separated by 100 miles of road. Their proximity allows them to be visited on a leisurely journey: not just a journey from north to south, but a journey through the rise and fall of the monastic communities of medieval Britain.

Rievaulx Abbey. Image: LOOP IMAGES/MIKE KIPLING

Rievaulx Abbey

Rievaulx Abbey was founded in 1132, the first outpost of the Cistercian order in the north of England. The White Monks (so-called because of the color of their robes) spread rapidly after their formation in France, and Rievaulx was intended to be a mission center from which the Cistercians could colonize the north and Scotland.

Image: Dana Huntley

Rievaulx Abbey was strategically built in a valley on the edge of the North York Moors, protected against the harsh winds off the North Sea. On the plateau above the valley, the 18th-century landscape garden of Rievaulx Terrace includes this domed Tuscan Temple, whose pavement floor came from the choir of the abbey below.[/caption]

Rievaulx is easily missed, tucked away in a North Yorkshire valley, surrounded by woodland. Only as you get close do the trees part and the great abbey unveils its full glory. The impressive ruins have a golden shine when caught by the sunlight and include extensive remains of the church, one of the finest in the country during its prime. Surrounding is a complex maze of low walls plotting the remains of many other buildings that were necessary to support life at the abbey.

Don’t miss the best view from Rievaulx Terrace. This modest 18th-century landscape garden follows a twisting course along the side of a hill overlooking the abbey. At either end of the terrace stand two folly temples. They were built long after the abbey had fallen into ruins, and the temples reused the conveniently scattered stones in their own flooring.

Perhaps because of its secluded location, Rievaulx is often overlooked by modern visitors in favor of its more illustrious North Yorkshire sister, Fountains Abbey. Yet Fountains had rather inauspicious beginnings and might have not survived beyond its first winter. A group of reform-minded monks from the Benedictine house of St. Mary’s in York fled from their community in 1132 to pursue a harsher and more disciplined way of monastic life. The community suffered severe hardships in its early years and was on the point of disbanding. However, the arrival of several wealthy recruits brought a change in fortunes and secured their future, and in 1135 the brothers were welcomed into the Cistercian family.

Image: Gregory Proch

Fountains Abbey

Cistercian monks had no personal property and worked the land with their own hands to support themselves, but the monks at Fountains were also successful entrepreneurs. They created a network of estates in more than 200 different locations that provided a large income.

Fountains became the largest and richest of the British monasteries and headed an extensive family that extended to the shores of Norway.

Today, the ruins at Fountains include some of the most impressive Cistercian remains in Europe and form Yorkshire’s first World Heritage Site. The western range, which survives in good condition, was primarily used by the lay brothers who worked and lived at the abbey. About 140 could have been provided for; the refectory occupied most of the lower story, but there was also cellarage, a cellarer’s office, and an outer parlor. An open-plan dormitory ran the entire length of the upper level.

Construction work at Cistercian abbeys was never-ending, and by the end of the 15th century, it was decided to build a new tower outside the north transept of the church. This magnificent stone structure was about 50 meters tall and dominated the site. It still stands almost to its full height and remains the hallmark of the abbey. Abbot Marmaduke Huby was so proud of the work that he inscribed his motto, Soli Deo Honor et Gloria (Honor and Glory to God Alone) on the tower. He also added a carving of a shield bearing his initials between a miter and crozier, and a stone head on the second story may be a likeness of him.

In winter, Fountains can seem cold and dead. But when the spring sun makes an appearance, and the days begin to warm, crowds flock to enjoy the manicured lawns and gardens along the lake by the abbey. Local families arrive with picnic hampers, and children playing among the ruins show that Fountains is not dead at all; it is merely hibernating, waiting to be roused by the laughter of youthful play.

If a reverential atmosphere is more your thing, you can escape the crowds by climbing the paths from the gardens and enjoy a view of the abbey peeping out from the greenery at Queen Anne’s Seat, named after a decapitated statue that stands in that spot— though the lack of a head must prevent her from enjoying the view.

Image: Scott Reeves

Kirkstall Abbey

The Cistercians were not confined to North Yorkshire. As the order continued to expand, a daughter abbey of Fountains was founded at Kirkstall in West Yorkshire. The ruins, three miles from Leeds city center, are easily accessible to visitors. The abbey estate is bisected by the A65, but this is a little problem compared to earlier years—in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the main road to Leeds actually ran through the nave of the church!

Bearing this in mind, you’ll find the structure of the church survives in relatively good condition. The opening for a massive window in the east end of the church, which stretched almost the entire width of the wall, draws the eye and invites you to imagine how magnificent the abbey must have looked at its peak.

Kirkstall draws the nearby population just as successfully as Fountains. Picnicking families are joined by local students who take a break from playing ball games to wander through the abbey ruins via the new visitor center, ingloriously housed in the old lay brothers’ toilet. However, this does allow consideration of the more mundane (but equally impressive) achievements of the Cistercians. Few medieval people got the chance to use flushing toilets, and the monastic waste was likely stored in a tank underneath the floor ready to be used as fertilizer, although the monk with the responsibility of digging it out may not have viewed the ablution facilities with such pride.

One of the most complete examples of a medieval abbey, Kirkstall sits in idyllic parkland just a few miles from the bustling industrial city of Leeds

For visitors who want a little more history, the Abbey House Museum next to the car park re-creates the streets of Victorian Leeds, from the retail therapy of a 19th-century High Street to the ominous presence of the undertaker, sited conveniently close to the re-created houses of the poor.

Roche Abbey

Back on our medieval journey: 1147 was the “golden year” for the Cistercians, during which the order did most to reach far afield. In that year, the same one when the future monks of Kirkstall were leaving Fountains, another Cistercian house was founded. This one, in the Maltby Beck valley in South Yorkshire, is a little-known gem that doesn’t have the throngs of visitors that the others enjoy.

Now, only a small part of the eastern end of Roche Abbey remains standing to any height, but this was once a splendid church, one of the earliest built in the “New Gothic” style in northern England. The use of clustered piers pointed arches and rib vaults created a greater sense of space, height, and light. Construction of the stone church began around 1170, some 20 years after the founding monks had arrived at the site. It probably replaced an earlier wooden building, for Cistercian rules prescribed that a temporary structure should be erected before the arrival of a new community so that they might straightaway serve God there.

The general fortunes of Roche mirror those of other monastic houses: a time of growth and prosperity in the 12th and first half of the 13th century was followed by a period of gradual decline that began with the arrival of a few rats and their fleas. Despite their isolation, the Black Death hit the population at Roche, and they never recovered. Although we do not know the precise numbers of those who died at Roche, we do know that four abbots presided at Kirkstall during the seven years from the outbreak of the Black Death and that the nearby abbey at Meaux lost three-quarters of its brothers.

Only the eastern end of the abbey church remains standing at Roche Abbey in the wooded valley of Maltby Beck. Much was demolished in landscaping by “Capability” Brown

Along with many other monasteries, Roche Abbey ceased its working life under Henry VIII. Most of Yorkshire’s abbeys were voluntarily surrendered to the king in 1538, which allowed the monks to receive a pension. The abbey buildings were destroyed to ensure that the communities could not reform. At Kirkstall, the church was stripped of anything of value, including roof lead and furnishings. Roche and Rievaulx abbeys were damaged with greater zeal, and a contemporary account from Roche records that “all things of value were spoiled, plucked away or utterly defaced.” Fountains had a stay of execution for another two years, while Henry considered using it as the base of a new bishopric. Inevitably, however, the abbey received the same treatment as the other Cistercian houses.

At the edge of South Yorkshire, my journey was finished—but the history of the Cistercian abbeys is not. After centuries of gradual decay, they are now under the care of local government and heritage organizations and offer a tranquil retreat away from the hustle and bustle of the 21st century. Long may this stage of their journey last.

* Originally published in 2016.

Comments