rudolf hess’s bizarre mission to britain in may 1941 still manages to generate controversy.

[caption id="OneWayFlighttoScotland_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

©HULTON/ARCHIVE

tHE AIRPLANE, A TWIN ENGINE MESSERSCHMITT BF 110, droned westward through the late spring evening, over the North Sea toward Scotland. It was 10th May 1941. Far to the south, German bombers were bound for London to deliver the fiercest attack of the blitz. This single aircraft, by comparison, offered little threat, yet the radar station in Ottercops Moss, near Newcastle-on-Tyne, noted its approach and sounded an alert. Responsibility for intercepting the intruder belonged to the RAF’s 13 Fighter Group, at airbases around Edinburgh. One of the group’s sector commanders was Douglas Douglas-Hamilton, the Duke of Hamilton.

The airplane roared over the Scottish countryside at treetop level, but no RAF fighter ever intercepted it. The Messerschmitt passed over Dungavel House, the Duke of Hamilton’s home near Glasgow, headed west to the sea, and then returned inland. Finally the pilot rolled his aircraft, struggled from the cockpit, and plunged into the night air. His parachute blossomed and lowered him to a rough landing on Scottish soil. David McLean, a ploughman from a nearby farm, reached the intruder as he was trying to get out of his parachute, hobbled by an injured ankle. The aviator, a man with prominent bushy eyebrows, a square-jawed face, and deep-set eyes, told McLean that he was German and said his name was Alfred Horn. “Will you take me to the Duke of Hamilton?” he asked. Instead, members of the Home Guard soon arrived and took the man to their headquarters, and from there to a military barracks in Glasgow.

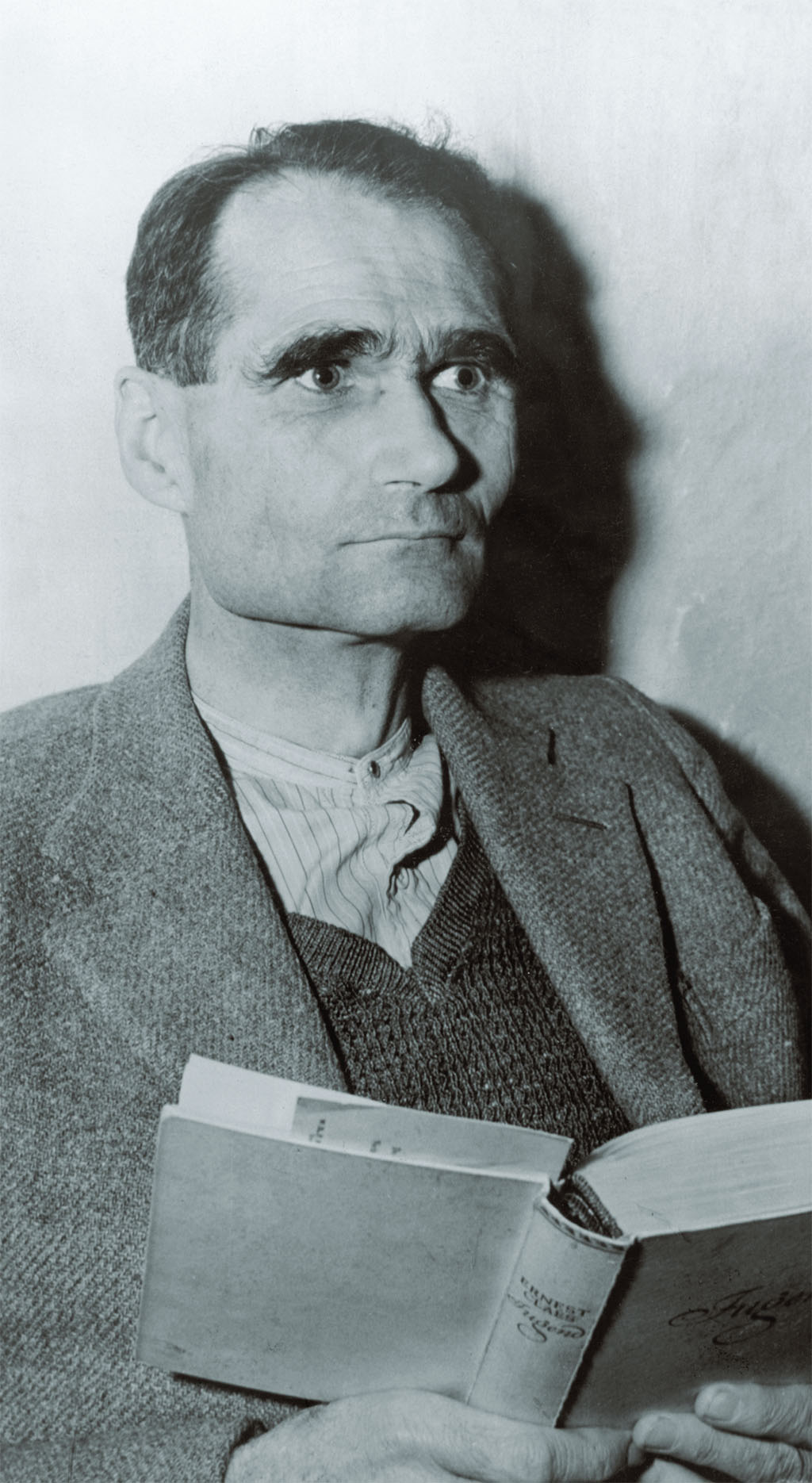

[caption id="OneWayFlighttoScotland_img1" align="aligncenter" width="590"]

©HULTON/ARCHIVE

The next morning the Duke of Hamilton arrived to speak with the German. The aviator made a spellbinding announcement. He was Rudolf Hess, he said, Adolf Hitler’s deputy Führer. He had come to offer peace to Britain. In return, he said, Germany would promise to leave Britain and its empire alone, provided that the Nazis received a free hand in Europe. But before any negotiations could take place, the Government of Prime Minister Winston Churchill would have to be removed.

Churchill was spending the weekend at a private home in the country, where he received word about the battering the Germans had given London. “There was nothing that I could do about it, so I watched the Marx brothers in a comic film which my hosts had arranged,” he later wrote. The Duke of Hamilton arrived that evening and met with the Prime Minister, and the two men went to London the next day. “There has never been such a fantastic occurrence,” John Colville, Churchill’s private secretary, wrote in his diary about Hess’s arrival. “In the Travellers at lunch-time there was no other topic. The rumours and theories are diverse and amusing.”

More than 60 years later, the rumours and theories remain diverse, occasionally amusing, and often contradictory. That is hardly surprising. Hess’s story is certainly odd, “one of the most bizarre episodes in the history of the two Great Wars,” in the words of Hitler biographer Alan Bullock. Most historians have accepted Hess’s account that he was acting on his own to broker a peace between his country and Britain so Germany could concentrate on what Hess perceived to be the real enemy-the Soviet Union. Others have spun more elaborate theories. Did Hess act with Hitler’s knowledge and approval? Was he merely a eat’s paw in a British plot to trick Hitler into attacking the Soviet Union and launching a two-front war that Germany could not hope to win? Was The Duke of Hamilton part of a strong and active “peace party” within Britain with which Hess hoped to negotiate? Was the man who arrived in Scotland really Rudolf Hess at all?

[caption id="OneWayFlighttoScotland_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

©HULTON/ARCHIVE

The official version of events is fairly straightforward. Hess was born in 1894 to German parents in Alexandria, Egypt, and began attending school in Germany when he was 14. Once World War I began, Hess defied his father’s wishes and enlisted in the army. He was wounded—once with a serious bullet wound through the lung—and began taking flight training near the end of the war. After the armistice, Hess lived in Munich, as Germany staggered beneath the burdens of the Versailles Treaty. There he threw in his lot with the National Socialist German Workers’Party, later known as the Nazis. He became an acolyte of a fellow party member, a fiery Bavarian named Adolf Hitler, and served prison time in Landsberg Castle with Hitler after the disastrous Munich Beer Hall putsch in 1923. There Hess helped the future Führer write Mein Kampf. Hess remained close to Hitler as the Nazis rose to power in Germany, and in 1933 Hitler named him his deputy. As the Party’s leader, Hess was also responsible for approving many of the laws that targeted Germany’s Jews. He was, as American prosecutor Robert Jackson characterized him at the Nuremberg War Crimes trials, “the engineer tending the party machinery.”

While in Munich, Hess had fallen under the influence of Professor Karl Haushofer, a former general and a professor of a pseudo-science called geopolitics. Haushofer and, to an even greater extent, his son Albrecht played important roles behind Hess’s flight to Scotland. Although Albrecht was part Jewish through his mother, he became a rising star in the German foreign office despite a distaste for the Nazis and their leaders. (The German Gestapo would execute him in 1945 for his anti-Hitler actions.) He did retain an attachment to Hess, though, not least because the deputy Führer protected Albrecht and his mother from the Nazi’s anti-Jewish laws.

Once Hitler plunged Germany into war, Hess found himself pushed into the background as the Führer turned his attentions to military matters. “By his flight to England, Hess was probably trying, after so many years of being kept in the background, to win prestige and some success,” wrote Albert Speer, Hitler’s minister of armament and war production. “For he did not have the qualities necessary for survival in the midst of a swamp of intrigues and struggles for power.”

[caption id="OneWayFlighttoScotland_img3" align="aligncenter" width="574"]

©HULTON/ARCHIVE

Britain declared war on Germany after Hitler attacked Poland in September 1939. Karl and Albrecht Haushofer felt that war with Britain was unnecessary. Hitler also wanted to avoid all-out war with Britain. As he had written in Mein Kampf, “No sacrifice should have been too great in winning England’s friendship.” When Hitler began planning his offensive against the Soviet Union, Hess became even more concerned about ending the conflict with Britain. Prodded by astrological predictions and prophetic dreams, Hess climbed into his Messerschmitt Bf 110 at the airfield in Augsburg outside Munich in the late afternoon of 10th May. Before he took off, he handed his adjutant, Lieutenant Karlheinz Pintsch, a letter addressed to Hitler. Hess told Pintsch to bring the letter to the Führer if he had not returned within four hours. Five hours later, Hess was in Scotland.

WHAT DID THE FÜHRER KNOW. AND WHEN DID HE KNOW IT? Would Hess, the ultimate loyalist, have taken such drastic action without consulting Hitler? Eyewitnesses testified that the Führer was shocked and angry after Lieutenant Pintsch delivered Hess’s letter. Albert Speer was at the Berghof, Hitler’s mountaintop retreat in the Austrian Alps above Berchtesgaden, when Pintsch arrived, and he recalled suddenly hearing Hitler react with “an inarticulate, almost animal outcry.” Speer later told biographer Gitta Sereny that Hess’s flight was “the second worst personal blow of Hitler’s life,” the first being the suicide of his niece in 1931. The Nazi dictator must also have worried that Hess would betray the plans for Operation Barbarossa, the upcoming offensive against Russia. After much discussion, Hitler made a public declaration that Hess had gone insane. He also ordered that Hess be shot if he were ever captured.

Not everyone agreed with Speer’s opinion about Hitler’s role. High-ranking Nazi Ernst Wilhelm Bohle told a prosecutor at the Nuremberg war crimes trial that he had helped Hess with preparations before the flight, and that all indications were that Hitler was aware beforehand. Adding to the theory that Hitler knew, and in fact approved of, Hess’s mission are the curious circum stances of 5th May, when Hess and Hitler met for four hours. Another of Hess’s adjutants, Alfred Leitgen, later said he overheard snippets of the conversation, including the names “Albrecht Haushofer” and “Hamilton” and the phrases “No problems at all with the airplane” and “simply declared insane.” If true, Leitgen’s accidental eavesdropping managed to glean some extremely interesting nuggets from a four-hour conversation. The fact that Leitgen waited until 1988 to reveal his bombshell, though, must cast some doubt on his story.

hess’s flight was “the second worst personal blow of hitler’s life … “

WHAT DID THE DUKE KNOW. AND WHEN DID HE KNOW IT? Douglas Douglas-Hamilton had become the 14th Duke of Hamilton in 1940. Until then he had been the Marquess of Clydesdale, as well as a prominent amateur boxer and a famous aviator who had participated in the first flight over Mt. Everest in 1933. Even though Hamilton was Scotland’s leading peer, he does seem an odd choice as Hess’s British contact. Hess apparently had no connection with Hamilton, although their paths did cross when the then-Marquess visited Germany for the 1936 Olympics. Hess theorists expend much energy examining whether Hess and Hamilton actually met on this occasion. Hamilton insisted they did not.

It was Karl Haushofer who suggested Hess approach the Duke with his peace proposal. In the 1930s Hamilton had been a member of the Anglo-German Fellowship, which advocated better relations between the two countries, perhaps an indication that he would welcome peace overtures. Even more important, Albrecht Haushofer and Hamilton had become friends in the late 1930s and maintained a correspondence. Just prior to Germany’s attack on Poland, Haushofer wrote the Marquess and warned him that war was pending. Hamilton showed that letter to Churchill, then out of power in the Government, who passed the information on to members of the cabinet.

[caption id="OneWayFlighttoScotland_img4" align="aligncenter" width="800"]

©HULTON/ARCHIVE

On 23rd September 1940, Albrecht, acting under Hess’s instructions, wrote a letter to the Duke suggesting a meeting in a neutral country, perhaps Portugal. British intelligence intercepted the letter and did not show it to Hamilton until February—leading conspiracy theorists to wonder if intelligence agents carried on their own correspondence, under the Duke’s name, with the Germans in the interim. Air intelligence finally showed Hamilton the letter and suggested he arrange the meeting. Hamilton hesitated, perhaps unwilling to drag his friend Albrecht into an intelligence operation, or worried that he would be abandoned as an apparent Quisling if things went awry. Before the Duke could take any action, Hess was in Scotland.

Hess theorists wrangle over what role Hamilton really played. The Duke and his family remained adamant that Hamilton never met Hess and had no idea that the deputy Führer was about to pop in for a visit. Yet author John Costello, in his book Ten Days to Destiny, claimed that Hamilton not only knew, he also used his position as the RAF wing commander at Turnhouse, near Edinburgh, to ensure that no British fighters were scrambled to shoot down Hess’s plane. Nonsense, countered conspiracy debunkers Roy Conyers Nesbit and Georges Van Acker in The Flight of Rudolf Hess: Myths and Reality.

“Turnhouse was one of the sectors of No. 13 Group,” they wrote, “but was too far from the scene of the action for its fighters to intercept the enemy aircraft.” In Double Standards: The Rudolf Hess Cover-Up (2001), authors Lynn Picknett, Clive Prince, and Stephen Prior argue that the Duke was a key member of a British peace party, and he was expecting Hess as part of a plot to overturn the Churchill Government and put a pro-peace one in its place.

[caption id="OneWayFlighttoScotland_img5" align="aligncenter" width="800"]

© BETTMANNICORBIS

WHAT DID THE BRITISH KNOW. AND WHEN DID THEY KNOW IT? It’s true that Hess reached Scotland at a low point for Winston Churchill and his Government. The Nazis had overrun Europe, and only the “miracle of Dunkirk” had saved the British army, while the German Luftwaffe had been terrorizing British cities during the blitz. Some elements within the nation believed that further resistance was futile. “The official histories carefully masked the roles played by key players in the year-long effort to strike a deal with Hitler behind Churchill’s back,” John Costello wrote in Ten Days to Destiny. “Just how close this peace plotting came to succeeding has been concealed to protect the reputations of the British politicians and diplomats who had believed that Hitler was less of a menace to the Empire than Stalin.” Under this scenario, members of the British peace party sent out diplomatic peace feelers through a tangled web of negotiations and secret meetings. Historians have been trying to untangle the web, if it existed, ever since.

On the other hand—and it seems there’s always another hand when discussing the Hess case—Costello and others have also examined the idea that the peace feelers were merely a blind put out by British intelligence to lull Hitler into a false sense of security so he would attack Russia and lead his country to inevitable defeat in a two-front war. This idea that the peace party was actually British subterfuge surfaced as early as 1943, in an anonymous article written for American Mercury magazine. The peace party scenario, whether real or feigned, is a murky one—as Louis C. Klizer admitted in Churchill’s Deception, “The conspiracy theory gets very complicated and, at times, borders on the absurd.” But isn’t murkiness an element of many successful intelligence operations?

[caption id="OneWayFlighttoScotland_img6" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

© BETTMANN/CORBIS

WHAT DID THE RUSSIANS KNOW. AND WHEN DID THEY KNOW IT? Germany launched its surprise attack on the Soviet Union on 22nd June, just six weeks after Hess’s flight. The timing made the always suspicious Jose£ Stalin even more paranoid. The Soviet dictator suspected that Hess revealed Hitler’s plans to the British—and that the British seriously considered his peace overtures. When Churchill travelled to Moscow in 1944, he found Stalin “silly on this point.” Wrote Churchill, “When the interpreter made it plain that he did not believe what I said, I replied through my interpreter, ‘When I make a statement of facts within my knowledge I expect it to be accepted.’ Stalin received this somewhat abrupt response with a genial grin. ‘There are lots of things that happen even here in Russia which our Secret Service do not necessarily tell me about.’ I let it go at that.”

In fact, there are indications that Hess did tell the British about the impending attack on Russia. On 5th November 1941, U.S. Captain Raymond E. Lee wrote to Brigadier General Sherman Miles of the War Department’s military intelligence department and said Hess “gave warning of Hitler’s intentions to invade Russia.” The letter was declassified in 1989. Lee’s source for this assertion was Major Desmond Morton, Churchill’s intelligence aide. John Costello also examined KGB files that said a Soviet agent provided this same information to the Russians. Louis Klizer even concluded that the suspicions sowed by Britain’s apparent double-dealing with Hess were a root cause of the Cold War.

The authors of Double Cross argue that Desmond Morton was obviously planting a false story that Hess had betrayed the plans for Barbarossa. Churchill didn’t need Hess’s information, they argue, as he had already learned of Hitler’s intentions from deciphered German communications. Instead, Desmond was using this apparent leak “to convince Washington and Moscow that reliable information had come from Hess.” It was all part of a Churchillian plot to use information allegedly from Hess to manipulate his allies.

tHE DOPPELGANGER THEORY: W. Hugh Thomas concocted the most fantastic theory of all. Thomas was posted to Berlin in 1972 as consultant on surgery to the British Military Hospital. His responsibilities included Spandau Prison, where Hess lived out the life sentence he had received at the Nuremberg trials. In 1973 Thomas gave Hess a thorough physical examination and found no trace of wounds that Hess had received during World War I. “This man had not been shot in the chest during the First World War, or at any other time,” Thomas wrote. His conclusion: the man in Spandau was not Rudolf Hess. The Luftwaffe had shot down the real Hess over the North Sea and the “Hess” who landed in Scotland was a double, hastily sent to take the place of the dead deputy Führer.

Thomas conceded that his scenario was one of “fantastic complexity,” and Nesbit and Van Acker attacked it convincingly in The Flight of Rudolf Hess. They cited the evidence of Charles Gabel, who met with Hess at Spandau and wrote a book about his encounters. When Gabel told Hess about the doppel-ganger theories, he wrote, “Hess laughed heartily and told me that two British doctors, the director of a military hospital and a surgeon, had visited him to have a look at these famous scars, which they found, although they were not very visible…. “

Nonetheless, other writers have taken Thomas’s thesis and come up with their own variations. In The Sword and the Swastika, author Peter Alien decided the substitution took place after Hess was moved to the Tower of London in May 1941. Louis Klizer theorized that the substitution was made after Churchill had used Hess’s flight to deflect Hitler’s attention eastward, and the real Hess became a potential embarrassment. As Klizer wrote, “[I]f the British used Hess to negotiate a war that killed twenty million Russians, it would be important that Hess not be available afterward to tell of it.” The authors of Double Cross theorized that the real Hess died in the plane crash that killed the Duke of Kent on 25th August 1942 on the way to Sweden for a final push by the British peace party. And so on.

[caption id="OneWayFlighttoScotland_img7" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

© LEIF SKOOGFOR/CORBIS

tHE LAST MYSTERY: Hess’s behaviour only added to the obfuscation. Often paranoid, he complained that he was being poisoned. While in British custody he made a couple of apparently half-hearted suicide attempts—once by throwing himself over a barrister, another by stabbing himself with a bread knife. He claimed to suffer from amnesia and then on the eve of the Nuremberg trials announced that his amnesia had all been a ruse. Later he claimed to lose his memory again.

Hess—or his double—spent the rest of his life in Spandau. One by one the six other Nazi leaders there won their freedom until only Prisoner #7 remained. Even Churchill protested his treatment. “Whatever may be the moral guilt of a German who stood near to Hitler, Hess had, in my view, atoned for this by his completely devoted and frantic deed of lunatic benevolence,” he wrote. Hess’s fate remained under the control of all four Allied powers—the United States, France, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain—but the Russians refused to relent and release Spandau’s final prisoner.

Hess managed to generate uncertainty even by his means of death. On 17th August 1987, he was found dead at the age of 93, after apparently hanging himself with an electrical cord. Rumours immediately began swirling that he had been murdered. Hadn’t the furniture in the room been disordered, as though by a violent struggle? Weren’t the marks on his neck consistent with strangulation? Isn’t it true that two mysterious American officers were on the scene? Not even death could end the enigma that was Rudolf Hess.

TOM HUNTINGTON, a freelance writer in Pennsylvania, is the former editor of American History and Historic Traveler magazines. He wrote about Christopher Marlowe for the May 2003 issue of British Heritage.

Comments