It was a beautiful moonlit night, frost on the ground, white almost everywhere; and…there was a lot of commotion in the German trenches….And then they sang “Silent Night—Stille Nacht.” I shall never forget it. It was one of the highlights of my life

—Albert Moren, 2nd Queen’s Regiment

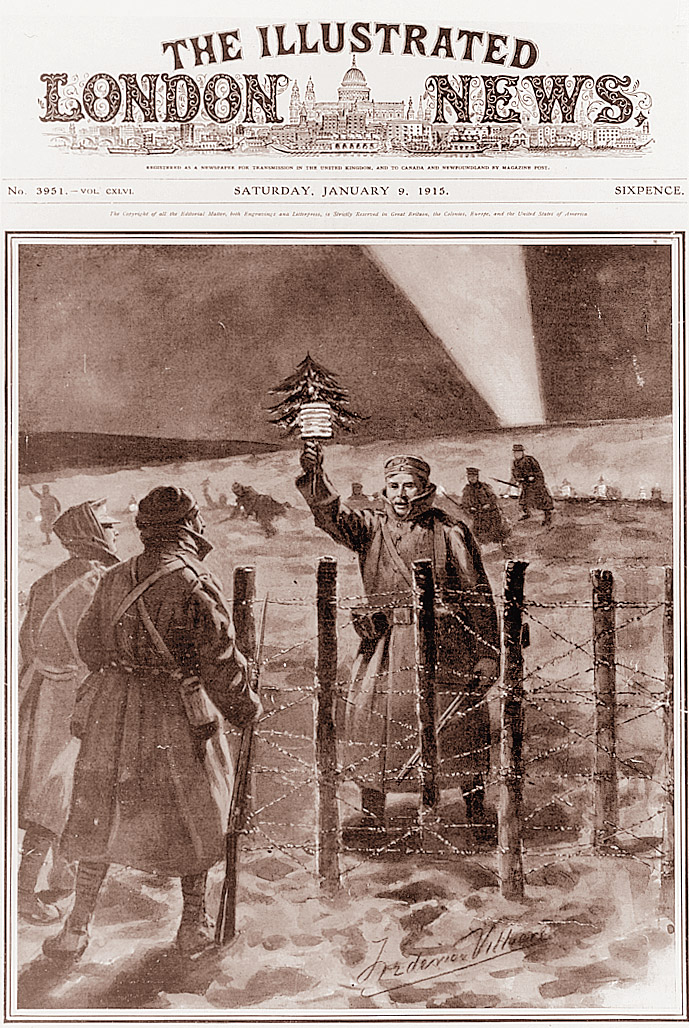

THE EVENTS THAT transpired on the Western Front during Christmas 1914 were so unlikely that many have since questioned whether they truly happened. Most British, French and German generals who passed the holiday season in relative comfort, far from the cold and despair that permeated the front lines, believed it would have been much better if, in fact, it hadn’t happened. But the facts are undeniable.

While 90 intervening years have provided ample time for some fanciful embellishments to creep into accounts of the first Christmas of the Great War, private letters written within hours of the events they describe leave no doubt that on December 24, 1914, something unique and unexpected happened—something that left a lifelong impression on many of those involved.

It’s impossible to say what prompted the frontline soldiers in what some see as history’s most horrendous conflict to briefly lay down their arms to celebrate their common holiday. Maybe the pope deserves the bulk of the credit. Only a few weeks into WWI, Benedict XV had called for a Christmas cease-fire. Or maybe this short peace was inspired in America, where the Senate had debated a resolution calling on the belligerent nations to observe a Christmas truce.

Almost certainly, however, the 1914 Christmas truce began at the very bottom—in the partially flooded trenches of Flanders, where bone-weary soldiers looked across the shattered landscape of no man’s land and saw men very much like themselves in the opposing trenches.

[caption id="PeaceforaMomentBreaksOutAlongtheWesternFront_img1" align="aligncenter" width="689"]

PRIMEDIA ARCHIVE

Spontaneous holiday celebrations began at sunset on Christmas Eve. In most sectors of the front, the German soldiers initiated the cease-fire. As darkness fell, the troops from the homeland of the tannenbaum began lighting tiny Christmas trees and placing them atop their parapets. Curious British troops, as well as Belgians and French, began poking their heads above their own trenches to catch a glimpse of the unusual spectacle—an act that would likely have been instantly fatal just a few hours earlier. Before long, shouts of “We won’t shoot if you don’t” received agreeable replies and, all hopes of the high command notwithstanding, the truce had begun.

Among those who experienced that remarkable Christmas Eve was Lieutenant Charles Bruce Bairnsfather, a reservist in the 1st Warwickshire Regiment who would later become famous for his cartoons based on life on the Western Front: “I came out of my dugout and sloshed along the trench to a dry lump, stood on it and gazed at all the scene around: the stillness, the stars and now the dark blue sky….From where I stood I could see our long line of zigzagging trenches and those of the Germans as well. Songs began to float up from various parts of our line.” Bairnsfather wistfully noted, “It was just the sort of day for peace to be declared.”

No one brought word of an armistice, but the next 24 hours saw little or no fighting along the length of the front. Rather than exchanging gunfire, Tommies and Jerries met in the midst of no man’s land to exchange makeshift gifts—cigarettes for beer, or bully beef for jam.

Souvenirs traded hands as well. The British troops most prized the odd spiked helmets worn by the German soldiers. They used belt buckles, buttons and other accouterments as the necessary currency with which to purchase such treasured keepsakes. Bairnsfather took part in the exchange of souvenirs. Spotting some fancy buttons on the uniform of a German lieutenant, he brought out his wire-clippers “and with a few deft snips, removed a couple of his buttons….I gave him two of mine in exchange.”

More grim than the sharing of gifts but perhaps even more conducive to creating strong bonds of comradeship, the opposing troops cooperated in burying each other’s dead, some of whom had lain for weeks in the previously inaccessible reaches of no man’s land.

The spirit of friendship among the combatants was not universal, however. An English private, Henry Williamson, later remembered one Austrian corporal who refused to join in the fraternization, or any of the Christmas festivities. One of the companions of the young corporal remembered that Adolf Hitler had said, “Such a thing should not happen in wartime. Have you no German sense of honor left at all?”

On the whole, though, the troops of both sides were of one mind. A gentleman’s agreement even arose among the enemies to prevent an accident or a single die-hard like Corporal Hitler from ending the truce prematurely: “If by any mischance a single shot was fired, it was not to be taken as an act of war, and that an apology would be accepted; also, that firing would not be opened without due warning on both sides.”

As midnight approached and Christmas Eve passed into Christmas Day, shooting was far from the minds of most of the soldiers. From time to time an angry officer ordered his troops to get back into their trenches and fire upon the enemy, but by an unspoken agreement such shots were always aimed well over the heads of their new friends.

Christmas Day began as no other day of the war had. War had taken a back seat to sport. All along the Western Front the nonbelligerent soldiers converted no man’s land into makeshift football pitches. “The English brought a soccer ball from their trenches,” noted Lieutenant Kurt Zehmisch of the German 134th Saxon Regiment, “and pretty soon a lively game ensued. How marvelously wonderful, yet how strange it was. The English felt the same way about it. Thus Christmas, the celebration of Love, managed to bring mortal enemies together as friends for a time.”

It’s unlikely that Corporal Hitler joined in, but for many others of all nationalities the football matches proved so friendly that even keeping score seemed like a needlessly provocative gesture. For Zehmisch’s opponents on the football pitch, soccer seemed like an antidote for war, and a practice worth continuing. “Towards evening the officers inquired as to whether a big football match could take place between our two positions tomorrow,” the German lieutenant remembered. Sadly, though, the 134th Saxons were being rotated out of the line on the 26th, and a new regiment would take their place. “We could not make any promise,” Zehmisch lamented, “since, as we told them, there would be another captain here tomorrow.

Zehmisch’s regiment had been scheduled to go into reserve even before the truce, but in other cases generals worried that such strong friendships had been formed on Christmas Day that the troops could no longer be counted on to attack their old enemies. In one German regiment, “the difficulty began on the 26th, when the order to fire was given, for the men struck,” Zehmisch noted. The officers “stormed up and down, and got, as the only result, the answer, ‘We can’t—they are good fellows and we can’t.’

Commanders on both sides rotated some of their regiments out of the line and replaced them with units that had not been present on Christmas Day. Bairnsfather had been realistic enough to keep his expectations low: “The respective soldiers having been sorted out, and put back into their proper slots in the ground, the war went on again. Bullets whizzed around that one-time meeting-place, and sundry participants in that social gathering were laid stiff on the parapets, awaiting burial.”

The British ministry, in fact, seemed embarrassed by the truce, and the official British history of the war brushed it off as an unimportant aberration: “During Christmas Day there was an informal suspension of arms during daylight hours on a few parts of the front, and a certain amount of fraternization. Where there had been recent fighting both sides took the opportunity of burying their dead lying in No Man’s Land, and in some places there was an exchange of small gifts and a little talk, the Germans expressing themselves confident of early victory. Before returning to their trenches both parties sang Christmas carols and soldier songs, each in its own language…. There was to be an attempt to repeat this custom of old time warfare at Christmas 1915, but it was a small and isolated one, and the fraternization of 1914 was never repeated.”

To those who had been there, though, like Albert Moren, it remained one of the most affecting memories of their lives.

Comments