[caption id="" align="alignleft" width="368"] COURTESY OF LINCOLN CATHEDRAL

How the charter King John was forced to seal 800 years ago turned out great

Anyone who knows the story of Robin Hood knows that King John was a bad lot. This was the evil Prince John, who persecuted the humble Saxon peasants and schemed to steal the throne from his older brother, the good King Richard the Lionheart. Despite a failed rebellion while Richard was in the Holy Land on the Third Crusade, when King Richard I died in France in 1199, his brother John inherited the throne of England quite naturally.

DANA HUNTLEY

With Richard having spent only six months of a 10 year reign in his English kingdom, though, John had become something of a surrogate ruler anyway. He may not have had the sheer villainy of the Robin Hood tales, but King John came to the crown with a firm grasp on his royal authority, surrounded by a schooled cadre of henchmen.

The Plantagenet monarchy, founded by his father, Henry II, and the strong-willed Eleanor of Aquitaine, was built for war and the exhibition of power. Any medieval monarch was only as strong as his armed force. At war with France, in 1204 King John lost most of his Anjevin inheritance on the Continent. The beleaguered monarch spent the rest of his reign—until his death in 1216—trying to live down the shame and regain his empire.

Known to be petty, cruel and spiteful, the King did not find it hard to alienate his barons with heavy taxation and heavy-handed treatment. During a failed French campaign to retake Normandy in 1214, a number of King John’s barons back in England began to organize rebellion against his authoritarian rule and excessive demands.

By the spring of 1215, nobles largely from the north and east of England had taken Exeter, Lincoln and most importantly London, and were determined to force the King’s hand. For a time, it appeared England would descend into civil war, and John’s ability to hold the kingdom was seriously in doubt.

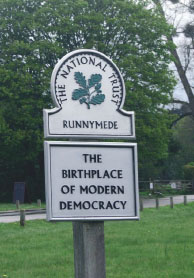

A peace was brokered between the King and the barons by Stephen Langton, the Archbishop of Canterbury. The parties met in June at the broad meadow of Runnymede beside the River Thames, between Windsor Castle and the barons’ encampment at nearby Staines. After the barons made their demands of King John, Langton spent 10 days mediating between them and drawing up the provisions of what was ultimately a treaty.

What became known as Magna Carta—the Great Charter—has been recognized throughout history (not only by the British, but all the English-speaking settler nations) as a seminal document in the development of constitutional, representative government. The charter King John was forced to seal under duress at Runnymede did not create any judicial rights for the vast majority of the King’s subjects. What it did, however, was acknowledge that the monarch was subject to the law and not above it—or worse still, that the King could make or change law by personal fiat. The protections of rights that the barons—the kingdom’s feudal tenants-in-chief—insisted upon codifying were their own.

[caption id="PeaceTreatyatRunnymede_img4" align="alignright" width="194"]

WORLD HISTORY ARCHIVE/ALAMY

Among its provisions, however, the treaty prohibited imprisonment without charge and provided for swift adjudication—the basis of habeas corpus. It bound the King not to take any extra-judicial action against persons or property, or to tax the barons without their consent. It also provided independence for the Church, and a measure of protection to cities, boroughs and ports, denying the King’s authority to curtail their liberties.

Following the ceremonies at Runnymede in June 2015 many copies of Magna Carta were made and officially sealed. They were sent to the shires, one to every English county to be proclaimed and recorded as law of the land. The provisions of the Great Charter were to be guaranteed by a council of 25 nobles, who promptly gathered and took their role seriously.

Both king and barons reneged on the agreement made at Runnymede within months, however, and the First Barons War erupted. Fortunately enough, King John died the next year. His heir was a boy-king, 9-year-old King Henry III, whose regents reaffirmed the Great Charter to placate the wary barons. Some 40 years later, an older King Henry III was challenged over his own authoritarianism by Simon de Montfort (see “Evesham’s Battle” a few pages on). Henry’s son Prince Edward defeated that rebellion, the Second Barons War, but unfettered royal rule was lost by the monarchy forever.

One by one, over the next two centuries each Plantagenet king reissued or affirmed Magna Carta. Over time, it became generally accepted as the root of England’s Common Law. As the Lords and House of Commons developed into a true parliament, many specific clauses of Magna Carta became codified into English law.

[caption id="PeaceTreatyatRunnymede_img5" align="aligncenter" width="762"]

DEANA HUNTLEY

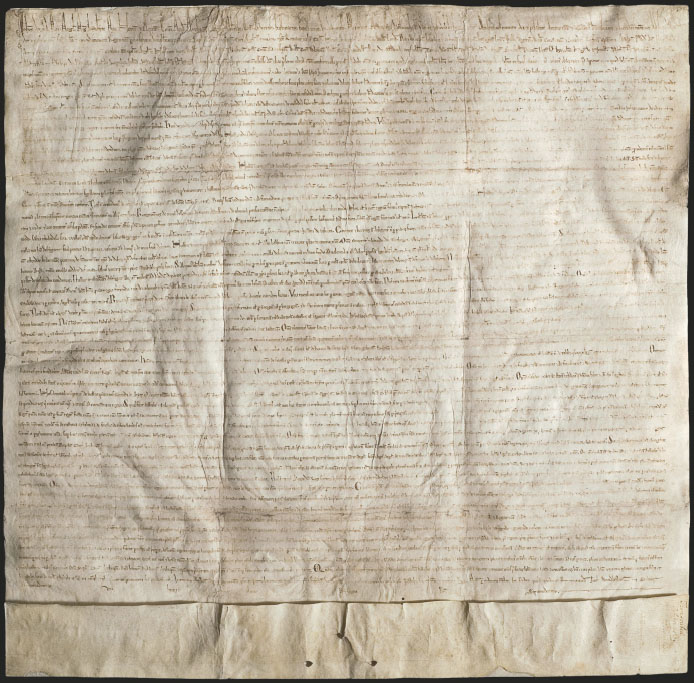

Over eight centuries, the vicissitudes of time have claimed the original 13th-century transcriptions of Magna Carta. Today, only four copies remain. Two of them belong to the British Library, one copy virtually illegible from damage by fire in 1731. The better copy is on public display in the Treasures Gallery at the library near London St. Pancras (www.bl.uk). A third copy belongs to 13th-century Salisbury Cathedral. It is on permanent display in Salisbury’s cathedral Chapter House.

The fourth surviving 1215 Magna Carta belongs to Lincoln Cathedral. Their copy has toured the world, lent out a number of times to highlight exhibitions on its historic threads. Most recently, it was on display from November to January this year at the Library of Congress in Washington, as the centerpiece of an exhibition to mark its hallmark anniversary and recognize its significance in our own political history.

The Charter returned to England this spring and to a new home in Lincoln Castle. British Heritage readers have followed the rebuilding of Lincoln Castle over the past couple of years (see May 2013, p. 34). This April, the completion of that mammoth project includes the opening of a new building just inside the castle grounds dedicated to the presentation and explication of Magna Carta. It sits just across the square from Lincoln Cathedral.

Today, the meadow at Runnymede is peaceful and public, next to the River Thames on the A303 just a couple of miles east of Royal Windsor and Windsor Castle (see “On the Road,” p. 12). Rather than contentious nobles and their banners, you’re more apt to see local folks running their dogs in the field. Park in the pay-and-display lot at the National Trust tea rooms (designed by Edwin Lutyens) and stroll the meadow.

The monument to Magna Carta lies in a hillside glen behind the meadow. Its classical, domed plinth was raised in 1957—by the American Bar Association. Its central pillar is inscribed “To commemorate Magna Carta, symbol of Freedom Under Law.”

Next to Magna Carta’s memorial stands an acre of American land: A copse and monument given to the United States in memory of President John F. Kennedy. On the ridge above the Runnymede meadow, and clearly sign-posted, the dramatic Air Forces Memorial stands in salute to thousands of Commonwealth airmen who died in World War II. Their presence reminds us just how far the roots of Magna Carta, confirmed there 800 years ago, have stretched across the centuries.

DANA HUNTLEY

Comments