Pottering about in The Potteries.

“There’s a slight wobble on it, but don’t worry—you never sell a pot while it’s spinning.” Pragmatism mingled with faint praise in potter Simon’s voice as he guided my first attempt at throwing a vase. I was aiming for something tall and slender, but settled for portly and squat, and felt unjustifiably proud.

If you visit the North Staffordshire city of Stoke-on-Trent, you simply have to get creative with clay in some way. The Potteries, as the area is affectionately known, is home to 350 ceramics-based businesses, including world-famous brands such as Wedgwood, Royal Doulton, Moorcroft, and Aynsley. Many venues offer the opportunity to try your skills, and I rolled up my sleeves at the Gladstone Pottery Museum. The vase-cum-tub now sits resplendent on my mantelpiece.

Right in the heart of England, Stoke is easy to reach by road and rail—the M6 slides by to the west, and train journeys from London Euston take less than 90 minutes. You could get about town by public transport, but car is far more practical, and the city’s website has handy maps that pinpoint attractions scattered around an 11-mile, north-south axis.

The centrally located Potteries Museum & Art Gallery is the first port of call for an overview of the area’s history and a glittering introduction to its pottery heritage. You’ll certainly want to view the Staffordshire Hoard of Anglo-Saxon warrior gear unearthed on farmland near Lichfield in 2009. You’ll also find displays on local heroes Arnold Bennett, who based his tales of Victorian working life in The Potteries, and Reginald Mitchell, designer of the Spitfire—there’s even one on view!

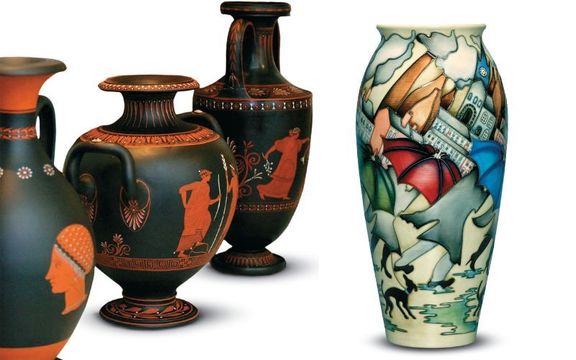

The ceramics gallery of 5,000-plus items is superb. Pottery has been made in the area since Roman times, but it wasn’t until the late 17th century that North Staffordshire became particularly noted for the craft. The ready availability of the key ingredients—clay, coal, and water—enabled cottage pot works to thrive, with one early specialty being the production of earthenware butter pots for farmers.

The six towns, Tunstall, Burslem, Hanley, Stoke, Fenton, and Longton, grew up close to the outcrops of coal and in the 18th century became the biggest center of pottery production in the world. The cutting of the Trent & Mersey Canal in 1777 revolutionized the transport of raw materials and finished wares and also secured supplies of coveted whiter clays from Cornwall, Devon, and Dorset. Pioneers like Josiah Wedgwood, Josiah Spode, and Sir Henry Doulton drove the industry onward, introducing new products, styles, and technology.

But there was a cost to all this splendor. The smoke-belching bottle ovens—there were 2,000 in their heyday—coated Stoke with grime and produced industrial squalor. It was an image that hung over the city well after the Clean Air Act of 1956 led to the termination of coal-firing. The recent “greening for growth” initiative has done much to enhance the city’s modern reputation—it now has over 3,400 acres of parks and open spaces.

In the latter 20th century, the industry also had to battle hard against cheap imported wares. In some instances, brands have joined forces or been taken over. However, all the potteries I toured were in good spirits, even noting an upturn in business; it seems some folks, at least, put their cash into products of substance in times of economic uncertainty!

Each individual pottery has its own unique character, and tough decisions have to be made about which to visit. I focused on two clusters of interest, around Longton and the south of the city, and Burslem to the north.

The Wedgwood Museum and Wedgwood Visitor Centre, at Barlaston to the south, are a must, to find out about the “Father of English Potters” Josiah Wedgwood (1730-1795). Born in the town of Burslem, the youngest of 12 children in a family of potters, he inevitably joined the business and later built a modern factory at Etruria, as well as a complete village for his workers. Pioneer, scientist (his grandson was Charles Darwin), workaholic, and shrewd commercial operator, he invented the iconic goods we know to this day: Cream-colored Queen’s Ware (1762), so named after Queen Charlotte chose it for a tea and coffee service, Black Basalt stoneware (1768) and the classically inspired bas-relief ware, Jasper introduced in 1774.

THE TRENTHAM ESTATE

Then, next door, the Wedgwood Visitor Centre adds insights into modern-day production, which moved from Etruria to Barlaston in the 1940s. These days tableware is outsourced, but Jasper and Prestige ware are produced exclusively on-site. When I visited, factory tours were not available (they may be revived), but I browsed the exhibition and craft skills demonstration area and watched Mary making bone china flowers, as she has done for 50 years: Deftly imprinting patterns with ordinary hair combs—a traditional technique—and wire meshing.

In the shop, I perused modern designs by Jasper Conran and Vera Wang and shamelessly eavesdropped as a Japanese gentleman parted with £350 for souvenirs. General manager Carole Hammersley later confided, “Wedgwood is a top luxury brand in Japan. They love our Wild Strawberry tea sets, launched in the 1980s.”

‘EACH POTTERY HAS ITS OWN CHARACTER,AND TOUGH DECISIONS HAVE TO BE MADE ABOUT WHICH TOVISIT’

IMAGES COURTESY OF THE WEDG-WOOD MUSEUM, STAFFORDSHIRE

Next up, Gladstone Pottery Museum where I threw my fabled pot was a thought-provoking step back in time. Also in the south of the city, at Longton, is the country’s last complete Victorian pottery factory, and what a compelling vision it gives of 19th-century Stoke as you trot through the maze of workshops and Engine House, past giant brick bottle ovens and across cobbled yard. This was once an ordinary, midmarket factory producing affordable bone chinaware, a follower not a leader. Whole families worked here, and it was a hazardous life: Potters’ rot (lung disease caused by clay and flint dust) was just one ghastly complaint I learned about in the Doctor’s House.

Gladstone’s ovens fired for the last time in 1960, and they looked set for demolition, but the site was saved in 1971 with the support of many local pottery companies. Its very “ordinariness” is now unique. A colorful Tile Gallery also illustrates the changing beauty and styles of ceramic walls and flooring, while the Flushed with Pride gallery “lifts the lid” on the history of the WC and the part potters played in its development.

There’s another tale of rescue at the 750-acre Trentham Estate, whose history spans from Domesday to the home of the Dukes of Sutherland in the 19th century. By the early 1990s, for various reasons, it was in terrible disrepair, until St. Modwen Properties Plc and German investor Willi Reitz purchased it in 1996.

The undoubted highlight is the re-creation and enhancement of the Italian Gardens designed by Charles Barry in 1842. Manager Michael Walker aptly commented as we stepped from the prosaic visitor entrance across the bridge over the River Trent, “This takes you through to Narnia. It’s like walking through Woolworths and finding Versailles.”

Lancelot “Capability” Brown’s mile-long lake immediately catches the eye, and around it the Italian Gardens have been infused with colorful new life thanks to perennial plantings by designer Tom Stuart-Smith. Piet Oudolf has created two 120-meter borders featuring salvias, echinacea and phlox, as well as ornamental grasses. There’s statuary, fountains and a 100-meter rose border plus a Trellis Walk exuding floral scents in summer. I nursed a refreshing cuppa in the Italian Garden Tearoom and drank in the glorious views.

Today the company sells more designs across the world than in its previous 1920s heyday. The key to Moorcroft’s success is the utter devotion to creativity and craftsmanship—Moorcroft’s four designers are given free rein, though their work is scrutinised by a committee. Swirling, dreamlike flowers, foliage and landscapes feature, all hallmarked by deep, vibrant color.

After viewing the museum of previous decades’ pottery, I took a factory tour. Casting, hand-turning, and decorating are carried out as they were a century ago, and I watched Alison tubelining—piping liquid clay along design outlines, a little like icing a cake: It’s Moor-test here 23 years ago, “floated in” colors within the raised design lines. Magic! Then and only then is a piece fired, with a second firing after glazing to attain those lustrous colors. When you see the time and craftsmanship that each handmade pot, lampshade or vase takes, you really appreciate the pricetag of quality.

‘GLADSTONE POTTERY MUSEUM IS THE LAST VICTORIAN POTTERY FACTORY’

Also in Burslem—it’s known as the Mother Town of the Potteries— are the contrasting worlds of the Moorland Pottery factory shop and Burleigh. Moorland may have a traditional setting of a cobbled courtyard and bottle kiln, but its small team is renowned for its humorous modern Stokie Ware. “Stokie” refers both to people from Stoke-on-Trent and their dialect. How about a hearty mug emblazoned with the iconic “Cost kick a bo agen a wo anyed it till it bost”? (Trans: Can you kick a ball against a wall and head it until it bursts?) It’s a soccer-mad area, with partisan fervor split between two teams, Stoke City and Port Vale.

At canalside Burleigh, I plunged back into the Victorian era. The firm built its reputation from 1851 and specialises in handmade blue-and-white crockery, with diversions as fashion dictates—red and black are the latest additions. I moseyed around the shop (like a huge country kitchen piled high with tableware), then head of production Paul Deighton whisked me off on a tour.

Up and down wooden stairs we went, past clay mixing, cup handling (Lynne has been adding handles to cups for 20 years), casting, fettling and all manner of 19th-century artisan techniques. I glimpsed a commission awaiting dispatch to Prince Charles—including egg cups and butter dishes depicting Highgrove hens.

Burleigh’s “jewel in the crown” is the now-rare underglaze transfer printing process, by which thin tissue paper printed from a hand-engraved copper roller is hand-wrapped—without wrinkles—around teapots and other such tricky-shaped items that have been previously fired to “biscuit.” Brushing, soft-soaping and then removal of the paper leaves behind a pattern. Further firing, glazing and firing produce the final piece. “People will always buy quality,” Paul said.

While in Burslem, I popped into Hamil’s on Hamil Road for traditional oatcakes cooking on a giant hotplate—they’re like bubbly textured, oat-flavored crepes, eaten with a variety of fillings. Recipes differ, and when you buy a business, you buy the secret recipe. “It cost me more than the building,” owner-cook Gary told me.

Across the road, I wandered around Victorian Burslem Park, where the gardeners interrupted their tea break to tell me about the multimillion-pound restoration. It’s a brutal truth that visitors don’t come to Stoke for its cityscapes—like many an industrial town that thrived in the Victorian era, it suffered postboom. But there’s plenty of ongoing regeneration including the enhancement of parks, while old rail lines have been claimed as greenways for cycling and walking, and the two canals that feed through the city, The Caldon and the Trent & Mersey, are popular leisure routes. It all takes resources.

What you do find, in addition to the visitor attractions, is friendly people, and there are some atmospheric old pubs. I rounded off my explorations of the north of the city with one further gem I would recommend. Ford Green Hall is a charming 17th-century timber-framed farmhouse, the home of wealthy yeoman farmers for nearly 200 years and furnished with the sort of ceramics and beautiful textiles they would have enjoyed. Slightly hidden in a dip from Ford Green Road, incongruously set opposite a modern carwash, it suddenly pops up and is full of historic allure. Characteristic of The Potteries, really.

A pick of The Potteries

Stoke-on-Trent’s website has good information on attractions, accommodation, food and drink, as well as useful downloadable maps of the towns, www.visitstoke.co.uk.

Words to the wise: Check for VAT reclaim facilities when purchasing your ceramics. Most factory shops offer an overseas delivery service, and factory seconds and discontinued ranges can be found at discounted prices.

Burleigh, Port Street, Burslem

www.burleigh.co.uk.

Moorcroft Heritage Visitor Centre, Sandbach Road, Burslem

www.moorcroft.com.

Trentham Estate, Trentham

www.trentham.co.uk.

The Wedgwood Visitor Centre, Barlaston

www.wedgwoodvisitorcentre.com.

* Originally published in 2016. Updated in 2023.

Comments