[caption id="ReViewingTheNationalTheatre_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

PAUL GREENLEAF

AGAINST THE NIGHT SKY, giant colorful computer screens outside the Royal National Theatre on the South Bank announce the evening’s productions. This year, the National Theatre celebrates its 50th anniversary, and it was a long time in the planning. After many decades of calls for a national theater, an act of Parliament was finally passed in 1948 and a site on the South Bank was designated for the building. It wasn’t until 1962, however, that construction plans were approved and work commenced. While waiting for its permanent new home to be built, from 1963 to 1976 the newly created National Theatre performed under the artistic leadership of Laurence Olivier at the Old Vic, just a short walk from the South Bank.

Today’s National Theatre pulsates with activity. Throughout the day there are talks and interviews about theater, backstage tours, a well-stocked bookshop, exhibitions and places to eat and drink. One doesn’t have to attend a play to enjoy the premises, but, of course, the plays are the main draw. Since the National Theatre presents plays in repertory, there is always something to see on its three stages—the Olivier, the slightly smaller Lyttelton and the intimate Cottesloe (soon to be completely renovated and renamed the Dorfman Theatre).

[caption id="ReViewingTheNationalTheatre_img2" align="aligncenter" width="661"]

MANUEL HARLAN

For the last 10 years Nicholas Hytner, brilliant stage and film director, has led the National Theatre, while raising its profile all over the world. While Britain’s Arts Council contributes some money, the National Theatre also depends on box office sales and traditional fundraising to meet its budget needs.

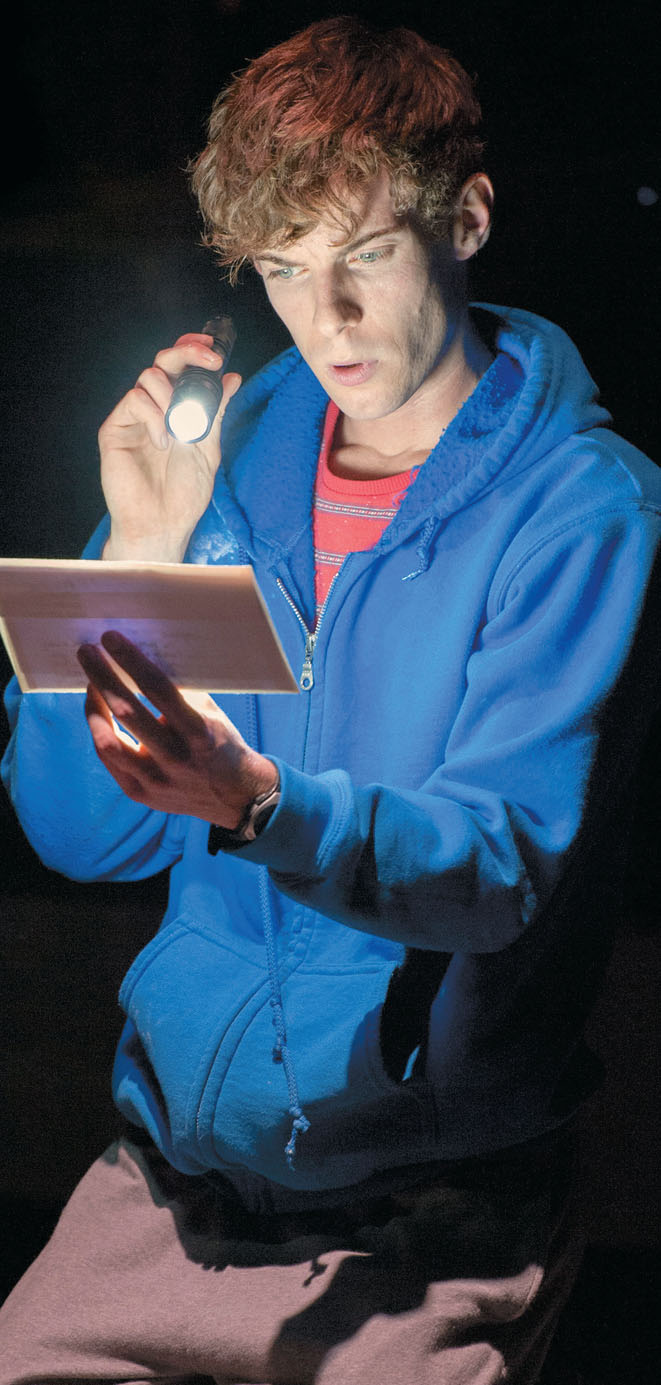

Hytner’s passion for the National Theatre is clear: “It’s commonplace to say that British theater is the best in the world; what makes it unique is that it’s still driven by the same spirit in which Shakespeare’s plays were mounted on the South Bank 400 years ago—vibrantly popular, public theater which goes all out to attract audiences with wildly different tastes. Last year’s Jubilee and Olympic summer, when the eyes of the world were on London, perfectly demonstrated how theater can vigorously explore the world around us. Our three theaters were as full of plays from the past which shed fresh light on the present, such as Shakespeare’s rarely done Timon of Athens, as they were for new plays like our adaptation of Mark Haddon’s book The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time.”

[caption id="ReViewingTheNationalTheatre_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JOHAN PERSSON

Looking ahead, a major redevelopment plan called NT Future will make the National Theatre more visible and accessible to everyone. While a new riverside cafe and public garden are to be developed as well as a new main entrance, it will be the plays, the stories that the National Theatre portrays on its stages that will keep it relevant for the next 50 years and beyond.

Hytner is excited for the challenge: “The National has become the busiest theater in the world and our global profile is higher than it’s ever been, with international tours and transfers of shows like War Horse and our National Theatre Live program of cinema broadcasts, which bring what we do at the National to a much greater number of people than we would ever be able to reach otherwise. We are restless to achieve more, however, whether for digital or live audiences here in the UK or abroad.”

—By Jennifer Dorn

For more information go to www.nationaltheatre.org.uk

The Origins of Parliamentary Government

[caption id="ReViewingTheNationalTheatre_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

©MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARY/ALAMY

BOOK

The First English Revolution: Simon de Montfort, Henry III and the Barons’ War by Adrian Jobson, Bloomsbury Publishing, New York, 239 pages, hardcover, $39.99.

BACK IN THE 13TH CENTURY, the king was the Big Boss. His word went in most matters; he was the law-giver, the lawbreaker and the supreme judge. Of course, no matter how indirectly, the king couldn’t hope to know and supervise every aspect of society across medieval England (let alone such French possessions as the kingdom included at any given time)—particularly given the nature and speed of medieval travel and communications.

In practice, England was both governed and ruled by an oligarchy—a few hundred tenants-in-chief, principal landowners and knights of the shires who exercised varying degrees of local control and political influence, largely based on the size of their holdings and the amount of military muscle they could bring to the battlefield. The king might have been the Big Boss, but he was never the sole source of practical governance, armed power or control of the public purse.

[caption id="ReViewingTheNationalTheatre_img5" align="aligncenter" width="444"]

In 1258, the barons coerced Henry III into formally sharing governance rather than ineptly attempting personal rule. The instrument was the Provisions of Oxford, which established a cabinet of 15 nobles and ecclesiastical officers to control ministerial appointments and legal administration. Henry bided his time, fuming at his lost authority and exploiting every opportunity to divide the already fracturing solidarity of the barons. In 1261, he had enough strength to formally revoke his assent to the provisions and assume personal rule.

Enter Simon de Montfort, the 6th Earl of Leicester (and the king’s brother-in-law). De Montfort had been among the leaders of the barons pushing for the Provisions of Oxford and the reform of Henry’s shoddy administration. His name had been first on the new council. When Henry took over again in 1261, de Montfort fled to France.

In 1263 the restive barons encouraged de Montfort to return and assume leadership of armed revolt to restore the government ordained by the Oxford provisions. At the Battle of Lewes, de Montfort and his allies triumphed, with the king and his son, Prince Edward, falling into the barons’ hands. The government fell to de Montfort.

While de Montfort’s scheme for reforming government was flawed, it was historic. He summoned a Parliament with two representatives from the counties and principal boroughs. Parliaments had certainly been held before. For the first time in European history, however, delegates were to be elected. Ultimately, as historians have noted for centuries, representative parliamentary assembly descends from de Montfort’s elected Parliament where freehold citizens had a right to vote for their representatives.

It all fell apart, of course. Prince Edward escaped and, in a world of private armies, soon had at his command enough force to reengage the battle for unfettered royal control. De Montfort was killed at the decisive Battle of Evesham in August 1265. What became known as the Barons’ War was over, and de Montfort is now remembered as the father of modern democracy.

That’s the nickel version, of course. In The First English Revolution Adrian Jobson has done a great job telling the whole story. Be warned. This is not atmospheric narrative, but densely written history. Jobson’s prose is clear and efficient, not decorative. It’s a “Just-the-facts-Ma’am” style that is refreshing, but challenging. There’s a lot of material covering a decade of oligarchic machinations in what is a relatively brief book. For providing a good introduction to the taproots of representative government, not to mention medieval politics, however, The First English Revolution does the job admirably.

Comments