Hiking across history on the Hadrian’s Wall Path

[caption id="RomanLegacy_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

SEAN MCLACHLAN

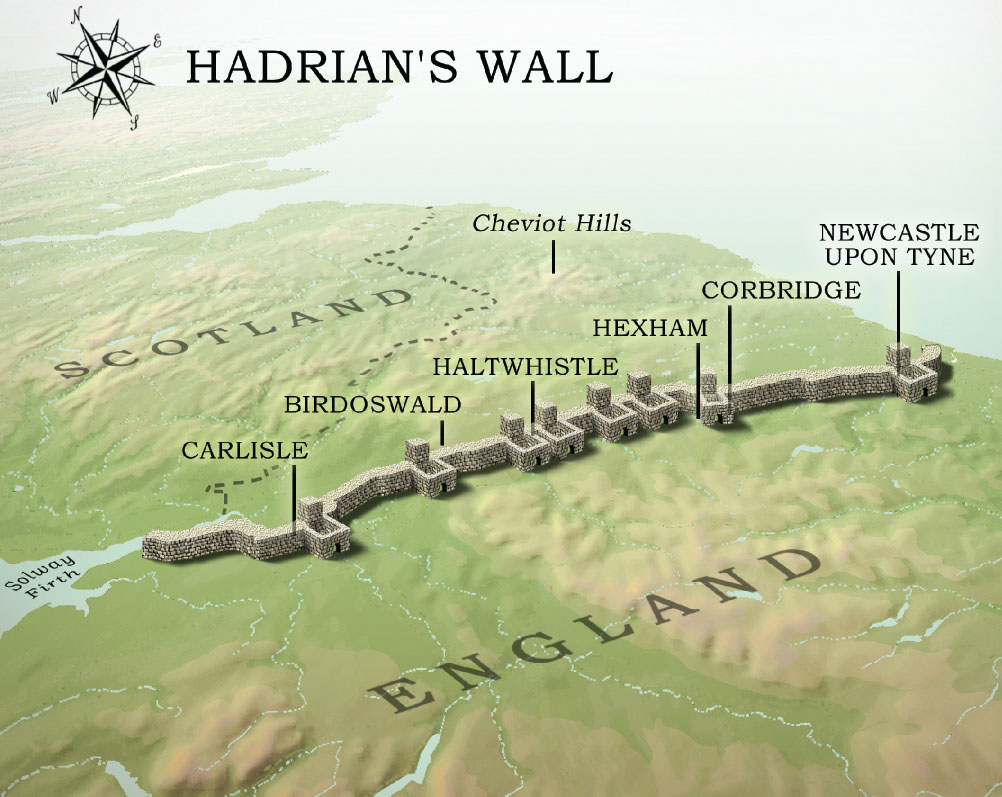

It has stood there for almost 2,000 years, guarding the border between England and Scotland. Hadrian’s Wall is a monument to the Roman Empire’s military power and technical ability, but it did more than protect the empire’s northernmost frontier. It left a cultural legacy still felt in the borderlands.

Roman Britain had constant trouble with the Picts and other northern tribes. As protection against their depredations, in AD 122 the Emperor Hadrian ordered that a wall be built from what is now Newcastle-upon-Tyne near the mouth of the Tyne River on the east coast to Bowness-on-Solway along the Solway Firth on the west coast. The distance was 74 miles. Fortified gates called Milecastles marked every Roman mile along the route. Between them stood lookout towers. Several large forts housed the legions and strengthened the defences. A trench was dug in front of the wall to the north, and a trench and a double set of earthworks called the Vellum was constructed behind it. The Romans not only wanted to keep hostile tribes at bay, but to monitor and tax any traffic headed in either direction. The Wall became a place for trade, and towns soon grew up around the forts.

In 2003 the government created the Hadrian’s Wall Path National Trail, allowing walkers to make a fascinating and relatively easy hike across northern England, where they can examine the preserved sections of the Wall and pass through several types of terrain—and 2,000 years of history.

[caption id="RomanLegacy_img1" align="aligncenter" width="846"]

SEAN MCLACHLAN

The Wall has gone through a great number of changes over the centuries. One of the biggest came after Bonnie Prince Charlie took Carlisle in 1745. The English army at Newcastle couldn’t save it because there was no road between the two cities that could carry artillery. To solve this problem the English built a military road in 1754. Now paved and designated the B6318, it follows the Wall for its entire length, sometimes irritatingly close, sometimes at a comfortable distance, sometimes right over it. Miles of Roman stone were used for the new road, causing a level of destruction the Picts couldn’t even dream of, yet it helped preserve what remained. Antiquarians were appalled and took a greater interest in studying the wall. In 1801, William Hutton walked the entire length of the Wall twice and railed against its wholesale dismantling. Other antiquarians conducted excavations and reconstructed portions of it. What remains today is largely thanks to these early visionaries.

The Path starts in the appropriately named neighborhood of Wallsend in eastern Newcastle. Here the Roman fort of Segedunum and the outlines of all its buildings are visible from a tall observation tower, which also gives a sweeping view of the modern docks, river and city. The Path begins at the western end of the fort. This section of the walk, despite passing through the heart of an industrial northern town, is surprisingly relaxing. The river is a constant companion to the left, and in spots bushes and wildflowers screen the view of the offices and industrial developments. An echo of the ancient past comes in the form of the 19th-century Swing Bridge, which sits on the site of a 13th-century bridge that itself was a replacement for a bridge Hadrian put up. A nearby medieval keep stands upon Roman foundations.

After about 12 miles westward the buildings begin to disappear and are replaced by patches of fields and forest. The city is soon left behind entirely, and a long slog up a hill leads to the first rest stop for the night, Heddon-on-the-Wall, a village barely outside Newcastle’s reach. Heddon-on-the-Wall is proud of its Roman past and the streets have names like Mithras Gardens and Trajan Walk.

This town is the first place outside Newcastle where part of the Wall is visible. A low section of stonework promises better things ahead. A medieval oven or kiln built into this part of the Wall tells its own story—the Roman fortification has been reused by later generations for their own purposes. In fact, the reuse of the Wall is as epic a story as its construction. It has even affected how modern farms are laid out. In many spots where Roman stone lies just below the surface, the land has been given over to grazing since no crops will grow there. Cows, horses and sheep wander amid crumbled walls and broken columns. Buried Milecastles make good field gates by providing a firm foundation for carts and tractors.

The Path continues through rolling farmland as the Wall and its earthworks become increasingly visible. Just before coming to the North Tyne, a tributary of the greater river, at a place called Planetrees, the Wall stands several courses high. When William Hutton visited this spot more than 200 years ago, he was horrified to find a local farmer dismantling the wall to build a new farmhouse. He begged the farmer to stop, and the fellow relented and spared this section.

[caption id="RomanLegacy_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

SEAN MCLACHLAN

West of the North Tyne the land gets increasingly rough and bleak, and for the next 28 miles the Wall bobs up and down over steep, windswept hills. In the center of this wild country, at the halfway point across England, is a series of rough crags with sheer northern cliffs. Farms are few and far between, and the Wall is much better preserved here than in the more populated lowlands. Several Milecastles and turrets stand as high as 8 feet. The northern fosse is a clear “V” cutting through the land, disappearing when the Wall is protected by a cliff but reappearing at each of the gaps between the crags. The Vallum to the south of the Wall is also well preserved, giving the visitor an idea of just how massive this earth-moving project must have been.

Between Milecastles 31 and 32 stand the ruins of a Mithraeum, a subterranean temple to the Eastern god Mithras. This deity was hugely popular in the Late Roman Empire, especially among soldiers, and for a time rivalled Christianity. The temple was built to resemble a cave, but is now open to the air. Replicas of the three altars stand at one end, and passers-by show their respect by placing flowers and coins on top of them just as the Romans did 2,000 years before.

[caption id="RomanLegacy_img3" align="aligncenter" width="995"]

SEAN MCLACHLAN

According to local belief, the ancient gardens the Romans planted survived in a wild state. A 17th-century account mentions that Scottish physicians went along the Wall every spring to gather the medicinal herbs that grew there. They believed the plants were descendants of those planted by Roman physicians.

Because of their impressive appearance and ancient monuments, the crags have generated a rich body of folklore. In one tale, King Arthur, Guinevere and their courtiers sit enchanted in a hidden cave, asleep until a bugle lying on a table before them is blown, and Arthur’s sword Excalibur is used to cut a garter lying next to it. Nobody found the secret cave until some local yokel knitting at the ruins of Sewingshields Castle (now disappeared but once in the vicinity of Milecastle 35) dropped his ball of yarn, and it rolled into the dark recesses of the stonework. Following the trail of yarn, he discovered the secret cave and Arthur’s court in all its glory. The scene was lit by a fire that needed no fuel to burn, illuminating the lords and ladies in all their finery. The farmer saw the fabled table with the bugle, sword and garter set upon it. Nervously he stepped forward and drew the sword. The eyes of the nobility began to open. Gaining courage, the farmer cut the garter and put Excalibur back in its sheath. The lords and ladies sank back in their chairs and closed their eyes. Just before King Arthur faded back into a centuries-long sleep, he exclaimed,

O woe betide that evil day

On which this witless wight was born,

Who drew this sword—the garter cut,

But never blew the bugle-horn.

[caption id="RomanLegacy_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1002"]

GREGORY PROCH

[caption id="RomanLegacy_img5" align="aligncenter" width="1002"]

SEAN MCLACHLAN

The witless wight fled in terror and could never find the magic cave again.

A mile to the south stands the fort of Vindolanda, where archaeologists uncovered a cache of letters now on display at the British Museum. They tell of all sorts of important and mundane matters, from a soldier’s request for leave to an invitation to a birthday party. The hypocaust from the fort’s bath started a local legend. The farmers of Victorian times didn’t know the burnt brick pillars that once supported the floor of the bathhouse provided space for a fire that heated the building above. They assumed they had found the kitchen of the faerie folk.

After another steep crag the Path arrives at Housesteads Fort, ancient Vercovicium, where prehistoric terraces to the south show that the Romans weren’t the first to settle here. During excavations of the east gate in the 19th century, marks from chariot wheels were found, showing the wheels were 4 feet, 8 and a half inches apart, the same distance as similar wheel marks in Pompeii and the same distance used in British railway gauges.

Antiquarian interest and talk of the Wee Folk didn’t dissuade people from reusing Roman stone. The well-hewn blocks helped build Anglo-Saxon forts, medieval castles and modern farmhouses. Some remains have managed to stay where they had been originally placed. In a pasture on the site of Aesica fort near Milecastle 43, a Roman altar sits exposed to the elements as sheep nibble the grass around it. On one side a jug is carved in low relief, still clear after almost 2,000 years of weathering. The altar sits at one corner of the field near the old Roman gatehouse, now the modern farm gate. Perhaps it’s always been there, a place to make an offering before crossing the border. A heap of coins on top of the altar shows today’s walkers carry on the tradition. At another spot, an old Roman milestone, a cylinder about 3 feet high, has been used as a gatepost. Its size and shape are perfect, and considering its weight, it’s probably not far from the spot where Roman engineers first set it down.

The borderland between England and Scotland was dangerous for much of its history, and Roman blocks made handy building material for fortifications. Anglo-Saxon roundhouses and Norman keeps both used stone from the Wall, and in later times local lords used it to construct pele towers to protect themselves from the Border Reivers, fierce clans that enriched themselves by plundering their neighbors. Pele towers dot the landscape along this border region, especially in the west where the crags give way to rolling lowlands.

[caption id="RomanLegacy_img6" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

SEAN MCLACHLAN

Birdoswald fort, just west of Milecastle 49, is a good example of how Roman remains found enduring use by later generations. Excavations revealed that the Anglo-Saxons built a hall within the old protective walls. In the late Middle Ages, a pele tower was erected using stone from the fort, and later a fortified farm was added. In the more peaceful 19th century, a decorative residential tower was put up. Now the site is a museum. This strategic spot was never abandoned for long.

After a few miles the Path descends into gentle terrain. Farms are once again common, and the Wall fades away into the stonework of pele towers and Victorian farms. Soon the Path leads to Carlisle. On Castle Street stands the Tullie House, a 17th-century home that preserves a Roman shrine.

The Path is interrupted by urbanism for only a few miles before heading out onto flat lowlands to the west. Only the barest traces of the Wall remain along the 15 miles between Carlisle and the Solway Firth; it’s a pleasant ramble nonetheless, made more pleasant by the occasional archaeological curiosity.

Another pele tower stands in the middle of Aballava fort in Burgh-by-Sands, almost at the western end of the Wall. In the 12th century, St. Michael’s church was built right in the middle of the fort with reused stone, and in the 14th century, Edward I added a stout church tower that doubled as a pele tower. Passing through the tower’s only entrance, a heavy iron gate inside the church, one enters a cramped interior lit by several arrow slits. People gathered in the fortified church at a moment’s notice and readied their bows to fend off any attack. As the farmers huddled inside, waiting for the brigands to go away, perhaps they took comfort from being in a house of God. And perhaps some of the more old-fashioned took comfort from the stone head of a pagan god set into the chancel wall.

Near Milecastle 76 stands Drumburgh Castle, a fortified manor house with narrow windows and a single doorway on an upper story. Roman altars decorate the garden, and the house is, of course, made with stones from the Wall. At this point the Path runs along the southern edge of the Solway Firth. Across the gray expanse of water, the Scottish hills appear out of the mist. The wetlands here are home to numerous birds and the walk is a quiet one except for their cries. The Path, which started in an industrial town under the shadow of huge steel cranes, ends at the village of Bowness-on-Solway under the shadow of trees.

[caption id="RomanLegacy_img7" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

SEAN MCLACHLAN

Walking the Wall

THE HADRIAN’S WALL PATH is 84 miles long, being slightly less direct than the Wall itself. Except for the crags, it’s easy going the entire way. For those who want to walk the entire length, the best publication is the official National Trail Guide, Hadrian’s Wall Path by Anthony Burton. It includes Ordnance Survey maps showing points of interest on and close to the Wall, and the text gives a lot of background on the area. Like most guidebooks to the Path, it takes the reader from east to west. While this puts the prevailing wind in your face, it means you leave the industrialism of Newcastle behind after the first day and head into an increasingly rural landscape.

Many people walk the Path in six days, averaging 14 miles a day plus side trips. A reasonably fit adult will have no trouble with this pace. William Hutton was 78 when he walked the length of the Wall, and when he got to the end, he turned around and walked right back again. Because there are numerous places to stay along the Path, it’s quite easy go slower and see more. Any walk of fewer than six days will mean missing much of interest. Those with limited time might want to go directly to the crags, as this is where the Wall is best preserved and the landscape is at its most dramatic.

Two websites are essential. The official National Trail website (www.nationaltrail.co.uk/hadrianswall/) gives an overview with much useful information, while Hadrian’s Wall Country (www.hadrians-wall.org/) provides a listing of accommodation along the Path, from comfortable B&Bs to basic campgrounds. National Trails publishes a pamphlet titled Where to Stay for Walkers, available at Tourist Information Centers in Newcastle, Carlisle and through the post.

[caption id="RomanLegacy_img8" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

SEAN MCLACHLAN

Comments