[caption id="Saltaire_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

www.britainonview.com, unless otherwise noted

THERE IS A SAYING IN THE NORTH OF ENGLAND that “where there’s muck there’s money,” and the Victorian mill towns of Yorkshire certainly saw plenty of both. On the high moors, the hill farms provided the raw materials for a thriving woolen industry nestled in the peaceful valleys below. The combination of natural resources, rapidly improving technology and free trade created a boom time for enterprising entrepreneurs as a new breed of innovative, rich and powerful men made their fortunes in the years between 1799 and 1850. In just a few years, the Industrial Revolution turned the production of textiles from a centuries-old cottage craft to a multimillion-pound industry employing thousands. The area around Bradford turned to the production of worsted, a fine woolen cloth, and the city and its surrounding towns quickly earned itself the nickname “Worstedopolis.”

[caption id="Saltaire_img1" align="aligncenter" width="598"]

www.britainonview.com

The newly rich mill owners displayed their wealth in their homes and workplaces. In 1840 James Marshall, the son of a draper in the city of Leeds, paid for the building of Temple Mill—a vast, single-story building with an exterior designed by the architect Joseph Bonomi as a copy of the Temple of Horus at Edfu in Egypt. Nearby mills were equally elaborate, with Moorish minarets standing alongside Florentine towers, while at the enormous Lister’s Mill, the 240-foot-high chimney was said to be large enough to allow a horse and carriage to be driven around its top. Even in death, families vied with each other, creating elaborate monuments to themselves like those still to be found in Bradford’s Undercliffe cemetery. Here, the Illingworth family mausoleum, with its Egyptian frontage complete with sphinx, stands alongside obelisks, Celtic crosses and Classical temples marking the last resting places of more than 123,000 Bradfordians.

If it was a boom time for some, for others life was very, very different. The populations of several towns doubled or even trebled in the space of one generation, especially after disastrous famines in Ireland brought a flood of refugees seeking work. Soon Worstedopolis became swamped by the tide of immigrants, and conditions rapidly deteriorated. In nearby Keighley, the authorities reported that a single outdoor toilet was shared by 29 households in one area of the town. Elsewhere, six privies served 90 overcrowded households. Raw sewage ran in the streets, flowing into cellars and basements where families slept. At times, roads became “almost impassable from excrement,” and disease was rife. Life expectancy dropped to a mere 18 years, and half of all children died before reaching their sixth birthday. One Keighley woman, Rebecca Town, achieved a terrible fame when she died in her 44th year having borne 30 children, none of whom survived infancy.

[caption id="Saltaire_img2" align="aligncenter" width="372"]

www.britainonview.com

For those children who did survive, life was harsh. The Factory Act of 1819 set a maximum working day for 9-year-olds at 12 hours, but it applied only to the cotton industry and was rarely enforced in the woolen mills. In 1825 a half-day’s holiday on Saturdays (only nine hours’ work!) was introduced for children, but workers could expect only three full-day holidays per year. It was difficult, dangerous work, with children crawling about under the moving weaving looms where a moment’s lapse of concentration at the end of a 12-hour shift could easily cost a finger, an arm or even a life—and often did.

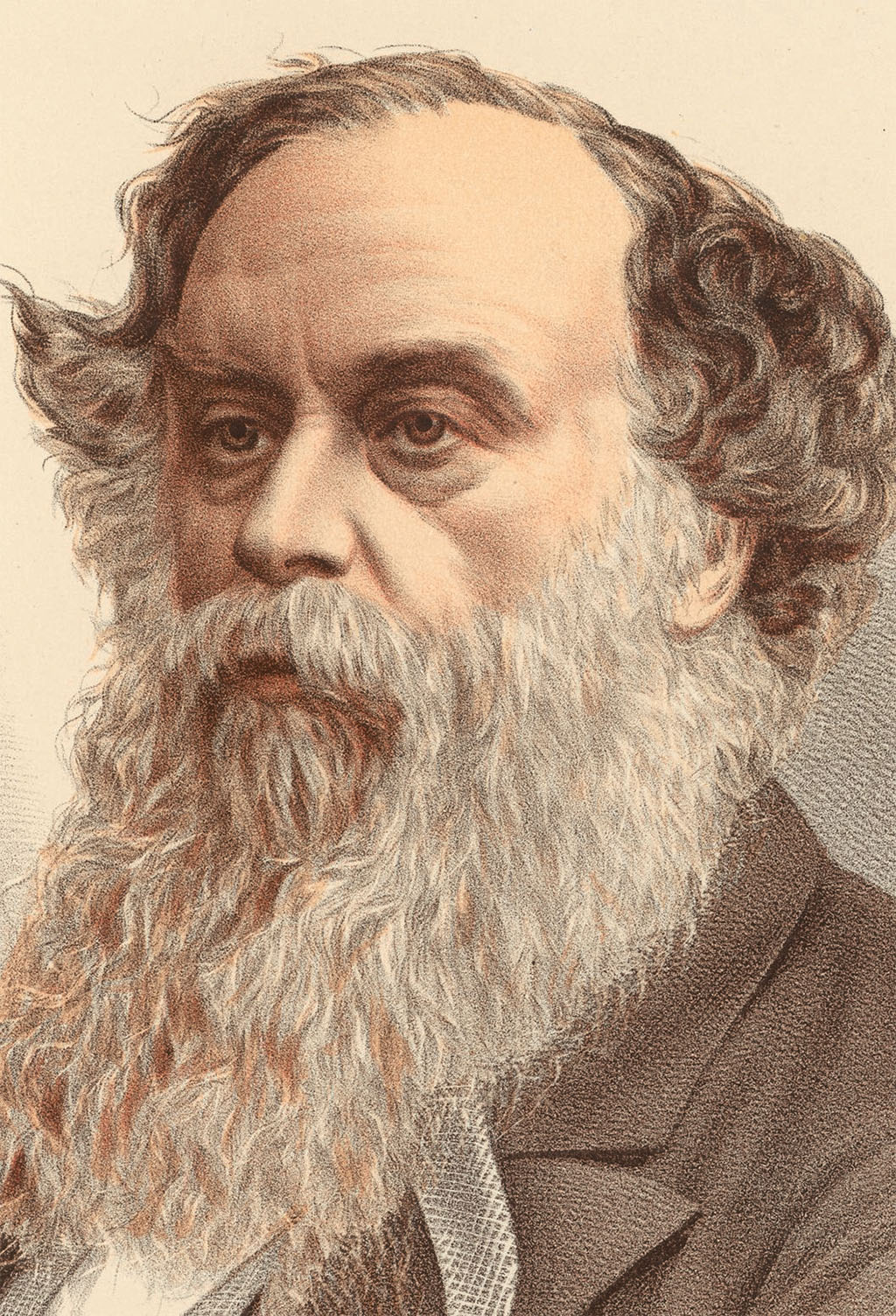

It was against this background that Titus Salt emerged as the world’s leading manufacturer of a new type of cloth. Born in 1803 to a farmer turned wool merchant in Bradford, Salt began working as a wool buyer at the age of 19. On a visit to Liverpool, he bought a quantity of cheap, evil-smelling alpaca wool and took it home to experiment. Eventually, by mixing it with silk, he developed first a fine, glossy yarn and then the techniques and machinery to turn it into cloth. He began producing Alpaca Orleans, a cloth so fine that Queen Victoria herself kept two alpaca llamas at Windsor and sent their fleeces to Salt to be turned into cloth. It would make Salt’s fortune.

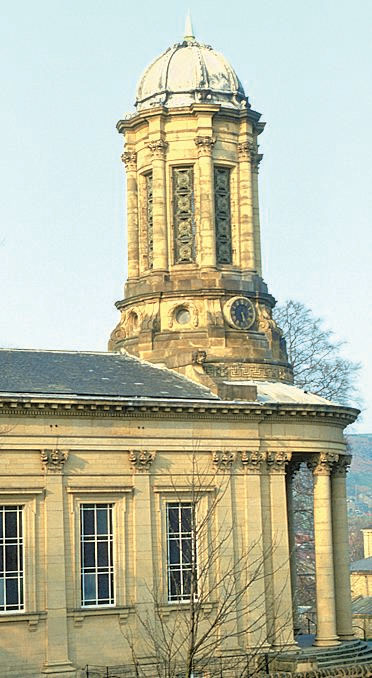

Salt was one of the emerging breed of philanthropic tycoons who saw the running of his business and care for his staff as part of the same task. As mayor of Bradford in 1849, he instigated a program of reducing pollution by improving drainage, cutting emissions from factory chimneys and providing parks and leisure facilities for employees. The following year, he set about an ambitious project that would ensure him lasting fame. Closing down his existing five factories, he began work on the building of Salts Mill three miles outside Bradford’s city limits. A palatial Italian-style factory with a chimney modeled on the campanile of the church of St. Maria Gloriosa Dei Frari in Venice and its noisy machinery sited underground, it was a showplace capable of processing raw fleece into finished cloth on its 1,200 looms and employing 3,500 local people.

[caption id="Saltaire_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Getty Images

Over the next 20 years, Salt added 850 houses for his workforce in streets named for his own children and for Queen Victoria. Alongside these, he paid for a hospital, a library, a church with seating for 600, cricket pitches, a boathouse, public baths and parks. There were no pubs, police stations or pawn shops in his model community; it was, quite simply, intended to be “a paradise on the sylvan banks of the River Aire, far from the stench and vice of the industrial city.” It is a mark of his achievements that when Sir Titus died in 1876, every mill for miles around closed in respect as 120,000 people attended the funeral of a local hero.

By the end of the 19th century, more than 350 mills were operating in Bradford alone, but already the industry was beginning to decline as new, man-made textiles replaced wool and cotton. A century after Sir Titus died, the industry that he had led also passed into history. For local communities it was a devastating blow. “You grew up thinking a job at the mill was your birthright,” recalled one worker who had started work in the 1930s at the age of 14. “When you entered the mill it just swallowed you up, it was your whole life.” But it was a way of life slowly coming to an end.

One of the last surviving mills, Salts Mill closed in 1986 and stood empty—seemingly doomed to fall derelict like so many others had—until a local businessman, Jonathan Silver, bought the 17-acre site in 1987 with the intention of turning it into a center for art and commerce. With the help of his longtime friend, Bradfordborn artist David Hockney, Silver created galleries and exhibition space where the looms once rumbled. Since Silver’s death in 1997, his family has continued to develop his vision. Their work was rewarded in 2001 when the whole village of Saltaire was declared a United Nations World Heritage Site, returning the community’s sense of pride in its unique home created by Sir Titus’ vision.

Today, Saltaire attracts thousands of visitors each year to roam its honey-colored streets and, with the help of the Saltaire Living History Project, to learn what life was like in the days when a whole town could be built on one man’s dreams.

-Tim Lynch

[caption id="Saltaire_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Getty Images

Comments