The Playhouse is the Ting…

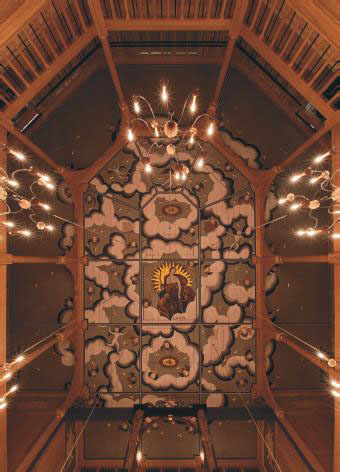

[caption id="SamWanamakerPlayhouseBringsJacobeanTheater_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

PETE LE MAY

[caption id="SamWanamakerPlayhouseBringsJacobeanTheater_img2" align="aligncenter" width="340"]

PETE LE MAY

IT SPARKLES! IT TWINKLES! It glows! It gleams! The phrase being bandied about is “jewel-box” and that, frankly, is the best word to describe the exquisite new Sam Wanamaker Playhouse. As a small bunch of journalists were taken on a pre-opening tour of the miniature Jacobean gem, there was a palpable feeling of awe from us normally-jaded journos.

It’s hard now to imagine a time when no one was convinced Shakespeare’s Globe Theater would work. Actor Sam Wanamaker found it almost impossible to raise enough cash to build what the snootier members of the arts world thought would be a horrible Disney-esque pastiche and the tourist executives thought would be too highbrow to tempt the hordes. Both were wrong, of course, and the Globe is one of London’s most respected theaters, attracting visitors and serious art lovers alike.

It is to Wanamaker’s credit that when he built the Globe, despite the nay-sayers, he also made provision for a second indoor theater to present some of the more intimate plays of the period. He couldn’t afford to complete it, so just built the shell, which was temporarily used as a rehearsal room. Now 16 years later, the Globe is a phenomenon with a turnover of £20m a year. They have raised enough money to complete Wanamaker’s vision, and the new Jacobean theater opened in January with a performance of The Duchess of Malfi.

There are no Jacobean theaters left, and virtually no designs for any, so the new playhouse had to be assembled like a gigantic 3D jigsaw puzzle from scraps and accounts in the libraries of the world. It is principally based on some rather sketchy plans discovered in Worcester College, Oxford, in the 1960s. The result is an archetypal playhouse of Jacobean times, rather than, like the Globe itself, a reconstruction of any particular place.

[caption id="SamWanamakerPlayhouseBringsJacobeanTheater_img3" align="aligncenter" width="703"]

MARK DOUET

The first thing that hits you as you walk into the minute space is the candlelight. Yes, naked-flame, actual candlelight: Dozens of real candles, on chandeliers above your head, in little niches and on sconces around the walls. The flames dance and twinkle, kicking out a surprising amount of light. Heaven knows what hoops they had to jump through to get permission, though I’m told the glorious central ceiling panel with a painting of the goddess Luna opens up to create a safety-chimney in the event of emergency and the place can evacuate in two minutes.

The second thing that hits is the smell—freshly-turned oak, melding with the wax to create a cocooning softness. The third thing is just how bloomin’ close you are to everything. The actors are almost at touching distance. Admittedly, “every seat is a trade-off,” according to Dominic Dromgoole, artistic director, when I asked him about sightlines. But what you can’t see from one seat, you’ll feel; what you don’t hear in another you’ll see.

That fire-provision Luna’s concealing under her dress isn’t the only thing the exquisitely painted ceiling hides. Although there is no actual electric lighting in the theater, there is provision for some, should a production require something a little brighter in the future. There are also hidden cameras so productions can be filmed, a silent air-con system specially designed so the candles don’t “wick” and clever under-seat lighting for emergency exits, (shut off under normal circumstances so that the experience is 21st-century-free). Another safety-feature-made-virtue is the series of windows onto a corridor so that, like original 17th-century playgoers, audiences can enjoy matinees with “daylight.”

It will be an odd experience for those audiences, used to sitting in the dark, a long way from actors, distanced from the stage both physically and emotionally. The most expensive seats will be the Gentlemen’s Boxes on either side of the stage, a hand’s touch from the action. These seats were traditionally bought by people more so they could be seen than to watch the action, and they are still very up-front. There are other intriguing viewing points from the minstrel’s gallery above the stage (where there is also a permanent harpsichord) and 30 “stander” positions up in the gods for anyone who enjoys the £5 groundling positions at the Globe—though these will be a tenner due to their rarity.

I’m hugely excited about this project. The building is truly beautiful, but what they intend to do with it—a program of Jacobean drama, including a resident troop of child actors to perform some of the plays and masques originally written for boys, early opera, candlelit concerts and some intriguing new writing—can only make London’s theater scene even more visceral.

– Sandra Lawrence

Book

Everything I Ever Needed to Know About ------—∗ I Learned from Monty Python: ∗History, Art, Poetry, Communism, Philosophy, the Media, Birth, Death, Religion, Literature, Latin, Transvestites, Botany, the French, Class Systems, Mythology, Fish Slapping and Many More!

By Brian Cogan and Jeff Massey, Thomas Dunne Books, New York, 304 pages, hardcover, $25.99

The comedy of deconstruction

THIS IS A BOOK for serious Monty Python fans. No, seriously. If you were part of the Monty Python legion back in your salad days, and you remember fondly the Spanish Inquisition, the Ministry of Silly Walks and the Philosopher’s Football Match, not to mention the Knights Who Say Ni, then this book will be a smile of recognition and a laugh down memory lane. Otherwise, it’s time for something completely different.

[caption id="SamWanamakerPlayhouseBringsJacobeanTheater_img4" align="aligncenter" width="257"]

Brian Cogan and Jeff Massey exhaustively deconstruct Monty Python (and its Flying Circus), the great deconstructers of modern comedy. With no subject too sacred and no artistic convention respected, the Pythons raved hilariously against authority of every kind—social, political, religious and intellectual. Erudite and well-educated in the liberal arts, the Oxbridge Python’s reveled in deflating literature, history, philosophy and the church. In a sense they were in the right place at the right time. Drawing their fans principally from college students and college-educated 20-somethings in the late 1960s and early ’70s, Monty Python tapped into the Zeitgeist. After all, questioning authority and long-held conventions were all the rage.

Cogan and Massey unpack Monty Python, the Flying Circus and its films in great detail. In truth, they go overboard attempting to be cute in a Pythonesque fashion, but for fans, that’s forgivable—and no one else out there will be interested anyway.

With the reunion of Monty Python this summer in sellout shows at the O2, a video version is inevitable. There will be a lot of revived Python buzz in our circles. If you’re an old fan and want to brush up on your Monty Python lore, Everything I Every Needed to Know is unquestionably the way. Unless, of course, it isn’t.

Comments