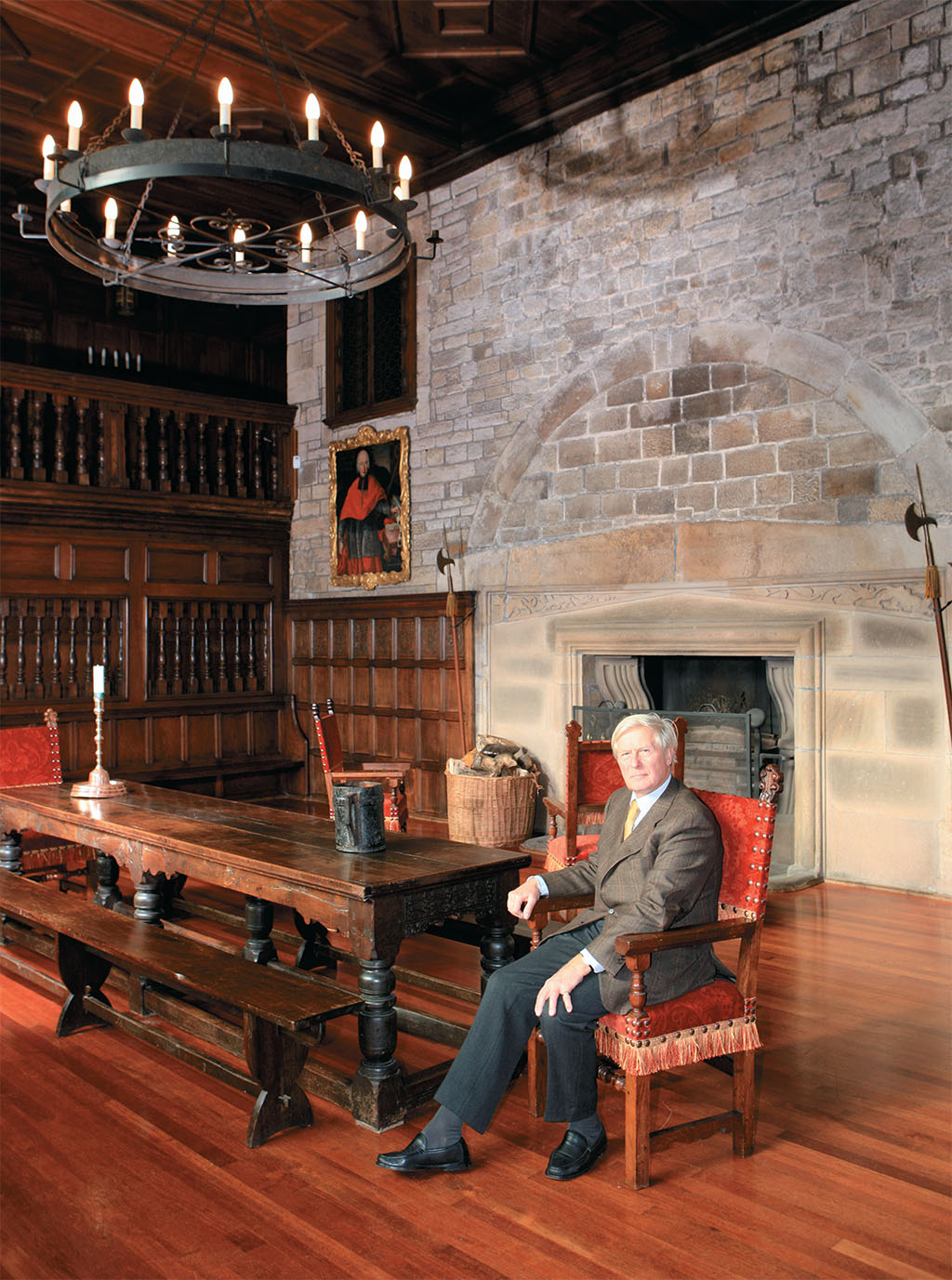

Sir Bernard, 14th Baronet, and Hoghton Tower

[caption id="SittingTightSincetheNormanConquest_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1018"]

PAUL FELIX

“It’s absolutely riveting,” declares Sir Bernard de Hoghton, 14th Baronet. He has settled himself comfortably at his large desk in his private study at Hoghton Tower, near Preston, Lancashire. He is silhouetted against a wall covered with bookshelves. “Shakespeare came here when he was 15 in 1579 and lived with the family until 1581. Alexander de Hoghton was his first patron,” he enthuses.

Gaps in Shakespeare’s recorded life have always attracted conjecture, and the most popular tale of his postschool years has him working as a tutor in the country. But in Sir Bernard’s family another oral tradition has passed down the generations.

“Read Professor E.A.J. Honigmann’s Shakespeare: The ‘Lost Years’, Professor Richard Wilson’s Secret Shakespeare and Michael Wood’s In Search of Shakespeare,” Sir Bernard urges. Then he launches into two detailed scenarios that explain how a young lad from Stratford-upon-Avon could arrive at Hoghton Tower. One focuses on the connections of Shakespeare’s Lancastrian schoolmaster John Cottam. The other suggests that Shakespeare came under the aegis of the Jesuit Edmund Campion, who had returned to England to reassert the Catholic faith in Elizabeth I’s reign. Campion stayed with the Hoghtons in 1580-81, where he knew he could work in relative safety.

“While at Hoghton, Shakespeare fell under the influence of Alexander’s resident troupe of theatrical players,” Sir Bernard continues. “He learnt from master of the revels Fulke Gillam—one of the Gillams who were Chester’s equivalent of the Burbages in London. Our Banqueting Hall, with its Minstrels’ Gallery and 16th-century windows that illuminate two bays with their huge galaxy of colored glass, would have been Shakespeare’s first professional acting space.

“When Campion was racked and executed in 1581, it must have had a terrible effect on the obviously Catholic William Shakespeare. That’s why he is so careful in his plays about not revealing himself through his characters.”

[caption id="SittingTightSincetheNormanConquest_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

PAUL FELIX

[caption id="SittingTightSincetheNormanConquest_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

THOMAS DE HOGHTON

[caption id="SittingTightSincetheNormanConquest_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

THOMAS DE HOGHTON

Sir Bernard goes into minute detail on a dozen more familial and professional links to support the case, as well as Alexander de Hoghton’s famous will (he died in 1581) in which he urges a neighbor to take care of Fulke Gillam and “William Shakeshafte”—a variant spelling of Shakespeare. The theme will certainly make a provocative chapter in the book about his ancestors that Sir Bernard is currently planning.

Another family might content itself with this fascinating claim to fame. However, for the de Hoghtons, the Shakespeare years are just one among many colorful passages in their history. They have lived on the same land since the Norman Conquest, can trace their line to the Saxon-Normanised de Busli (Bussel) family and are descended directly from Walter Pincerna, a companion of William the Conqueror. “Through the female line we go back to a wonderful lady—whose genes must be very strong because I’m a fair-haired chap—called Godiva,” Sir Bernard chuckles.

The family name, de Hoghton, derives from the Saxon “Hocton,” meaning “high wooded hill”: an apt description of the spot where their home stands, on a summit 650 feet above sea level with panoramic views across the Lancashire countryside, north to the Lake District and south to Snowdonia. Sir Bernard often draws inspiration from gazing out of his study window. “One feels very close to the people who would have looked at the landscape a thou thousand years earlier,” he says. “And the house gives a feeling of continuity, which I think is terribly important: The idea of who you are and what your roots are.”

‘THE HOME STANDS ON A SUMMIT WITH PANORAMIC VIEWS ACROSS THE LANCASHIRE COUNTRYSIDE, NORTH TO THE LAKE DISTRICT’

Further exuberant discussion follows about the views from his study, segueing between historic events and modern-day threats to the integrity of the landscape. It’s all part of one and the same story, which Sir Bernard effortlessly punctuates with dates and names, slipping into reenactments of likely conversations his ancestors would have had as they played their part in England’s dramas.

The home you see today, a manor house with two courtyards, is reached by a steep, three-quarter-mile drive and dates from 1565. Thomas Hoghton “the re-builder” was a true Renaissance man; he was also a Catholic and went into voluntary exile “for blessed conscience sake” during the upheavals of the Reformation. “This beautiful Elizabethan house is his epitaph,” Sir Bernard says. It was Thomas’ brother, Alexander, who hosted Shakespeare.

“This family was very much at the forefront of religious controversy and there has always been a martial spirit,” Sir Bernard says. “After the horrors of the Reformation we espoused the cause of Nonconformism. John and Charles Wesley preached here. As Knights Banneret of England we were involved in the Wars of the Roses. We’ve been at the forefront of the arts, theater and writing, too. Ben Jonson and Inigo Jones were friends, and later, in the mid 1800s, J.M.W. Turner came and painted our northern industrial skies from the Ramparts Turret.”

Throughout their long history the de Hoghtons made their way as courtiers, politicians, soldiers and country gents. Sir Bernard plucks a couple more scenes to savor. The first, in 1617, gave the family a story to dine out on for centuries. This time the host at Hoghton Tower was Sir Richard, who had been a page at Elizabeth I’s court, served in Ireland, been knighted and was a Baronet of the first creation. His guest was King James I of England/VI of Scotland.

The Merchant of Hoghton

The tale of Sir Loin provides a light-hearted impetus to Sir Bernard’s support of present-day British beef and produce. Every third Sunday in the month, the Tower hosts the Merchant (market) of Hoghton, with some 40 stands showcasing quality cheeses, meats, juices and other goodies from Lancashire and surrounds. “My wife Rosanna tells me I always buy far too much!” Sir Bernard chuckles, without a hint of remorse.

[caption id="SittingTightSincetheNormanConquest_img4" align="aligncenter" width="528"]

KATHY YEULET/123RF

[caption id="SittingTightSincetheNormanConquest_img5" align="alignright" width="1024"]

PAUL FELIX

In the Banqueting Hall a copy of the “Notes, Of the Diet, At Hoghton, At the King’s coming there, 1617” reveals Bluff Dick’s gargantuan largesse, from “boyld capon,” “beefe roste” and “curlew pye could” to “quailes 6 for the king” and “peare tarte.”

“Dick was a jolly good host. He could put six bottles of Rhenish wine under his silken doublet and still be on his feet,” Sir Bernard says.

The king was so pleased with the beef that he was eager for second helpings next day. And making a witty play on the French-derived surloin, it’s claimed he “knighted” the joint of beef Sir Loin, giving Britain one of its traditional dishes. You can still see the Great Beef Table where the meat was “ennobled,” or drop by the oak-panelled King’s Ante Chamber to see where he held court.

“Beef in those days was only just coming onto the tables; it really was a dish fit for a king,” Sir Bernard adds. Sir Richard had a good supply of horned, black-pointed white cattle in the forest, a breed commemorated in the white bulls of Hoghton on the family crest.

Some 25 years after King James’ merry jape, Parliamentarian forces came calling during the English Civil War. The central tower at Hoghton was blown up, killing 200 souls. “I think it was an accident,” Sir Bernard says. “I believe one or other of the Cromwellian soldiers lit his pipe and tapped some hot ash on what he believed to be wine butts but were actually black powder kegs. Boom!”

Like many families, the Hoghtons were split between allegiances to Royalist and Parliamentarian causes, leading to several family battlefield deaths. As in religious matters, they were never shy of pinning their colors to a standard.

Unsurprisingly, Sir Bernard’s home boasts a full complement of ghosts: The 16th-century Lady in Green bases herself in the Minstrels’ Gallery overlooking the Banqueting Hall and will helpfully advise any woman engaged in needlework; 17th-century priests including a Father Johnson; a 19th-century lady and child who appear in the Ballroom, quite at home amid the late Victorian decoration.

“They are not nasty presences,” Sir Bernard says. “Personally, I’ve only had one encounter. Let me put it like this: I would be much more worried by nasty encounters of the 21st century with living people than ones with people of another age.

“We have a very successful winter tourist system when people can book and visit on certain nights from November to February,” he adds. “We go through the spooky underground passages and outside, where some of the apparitions have been seen.”

As Sir Bernard’s comments suggest, life at Hoghton Tower in the modern age has brought as many challenges as did earlier times, if different in nature. When Charles Dickens visited in the mid-19th century, he found a home beset by romantic decay, which he described in George Silverman’s Explanation. Henry, Charles and Sir Bernard’s grandfather James, 9th, 10th and 11th Baronets, devoted themselves to restoration 1862-1901.

However, Sir Bernard recalls that when he succeeded as 14th Baronet in 1978, “I wasn’t quite sure, because of how my late brother Anthony had left things, whether there would still be an estate. He had spent a lot of time abroad. My lifetime on the estate since 1978 has been really to put things right.”

So how do the landed gentry get by these days? Gone are the retainers, replaced by a small number of employees and “very helpful friends and volunteers.” Pragmatism and commercial savvy are married to old-world, hereditary eccentricity. Sir Bernard has devoted himself to a second restoration, dealing with, among other things, a huge outbreak of dry rot. He set up Hoghton Tower Preservation Trust to channel proceeds from visitors and special events (the Tower opened to the public as early as 1946) into maintaining the house.

Nowadays, couples can celebrate their wedding day with canapés in the Inner Courtyard listening to a musical quartet, followed by a wedding breakfast in the Banqueting Hall. Businesses can hire rooms for corporate activities—as soon as we finish speaking, Sir Bernard dashes off to finish preparations for a symposium catering for 112 delegates: his enthusiasm for Shakespeare and Sir Loin transformed into double-checking seating and eating arrangements.

The wider estate has also presented huge challenges, largely influenced by modern changes in agriculture. “The estate around the house is now down to the size it was in the time of King Henry IV—we lost our Liverpool possessions on the turn of a card in the early 1800s,” Sir Bernard says with remarkable nonchalance. “From the outset I wanted to leave every Hoghton farming family on the farm—some 22 of them—so long as they could manage it and pay the rent. But many of the farmers are coming up to retirement and aren’t being followed by their children. The number of working farms has now reduced to seven.”

Visiting Hoghton Tower

Open to day visitors July-September: Sun 1 p.m.-5 p.m., Mon-Thurs 11 a.m.-4 p.m. Also Bank Holidays except Good Friday, Christmas Day and New Year’s Day.

Private tours for prebooked groups of 20 or more are available throughout the year. Prebooked winter evening visits November-February.

The Tower is midway between Preston and Blackburn on the A675 (six miles east of Preston). Nearest main railway station: Preston.

Hoghton Tower, Hoghton, near Preston, Lancashire Tel. 01254 852986; www.hoghtontower.co.uk email [email protected]

[caption id="SittingTightSincetheNormanConquest_img6" align="aligncenter" width="953"]

THOMAS DE HOGHTON

‘SIR BERNARD’S HOME BOASTS A FULL COMPLEMENT OF GHOSTS: THE 16TH-CENTURY LADY IN GREEN BASES HERSELF IN THE MINSTRAL GALLERY’

He is encouraging the remainder, without forcing them, to consider much bigger units, and also different crops. Among those farms that have been sold, he speaks of one now owned by a family that had been on the estate for 400 years. “They still consider themselves part of it, which is rather wonderful,” he says.

Fishing clubs, a shooting syndicate and the Holcombe Hunt also make the most of de Hoghton land. And Sir Bernard has plans to develop agro-tourism: Bringing groups of 30-60 people to Hoghton Tower on boats via the Leeds-Liverpool Canal, outside the main tourism season. Another idea is to rent out a tower or cottages on the estate.

“The de Hoghton family has always been very outward looking. We’ve never tended to look in at all,” he continues, citing the number of Baronets, including himself, who have wed non-English brides; his wife, Rosanna, hails from Florence.

This outward looking has also led to special ties with America. Suddenly, we’re again romping back through earlier centuries as Sir Bernard brings to life another succession of family members: One who sailed with Captain John Smith to North America in the 17th century; Ralph and John who settled in Massachusetts, where Ralph de Hoghton’s house can still be viewed. “On the outside it’s beautiful, on the inside it’s a fortress, precisely as an Englishman would have built his house in the ‘Wilderness Years’ of the colonies,” Sir Bernard says.

During the American Civil War, Sir Henry de Hoghton, 9th Baronet, and his American wife embraced the cause of the Confederacy, working on the English side of the Atlantic to send support. They lost £300,000 in the process. “That’s around £33 million today!” Sir Bernard exclaims.

“In more recent times, my father was honored in 1956 by the American Beef Council, for representing a family that had done so much for the meat industry, particularly the beef industry, following King James’ knighting of the joint of beef,” Sir Bernard says.

He himself has fond memories of studying history at McGill University, Montreal, and renewing friendships with overseas Hoghtons during many transatlantic visits. About five years ago, he set up the Hoghton American Association to strengthen familial ties, and recently a separate branch, the Hoghton Canadian Association, was established.

Time has whizzed by, conversation has flowed and Sir Bernard glances once more out the window. “I feel very strongly the sense of continuity, of guardianship and tenancy of a piece of land and this house,” he reiterates. Then he has vanished, off sorting out 21st-century concerns, with maybe an ancestor or two watching over his shoulder.

Comments