London’s hidden melting pot gets a makeover

[caption id="SpitalfieldsRevival_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

ANNA WATSON/19 PRINCELET STREET

“It was hardcore stuff,” says Oliver Leigh-Wood, recalling the dark days in 1977 when he and a small group of determined architecture enthusiasts squatted in a derelict Georgian town house to prevent the demolition men from moving in. “We had people there day and night, in pretty grim conditions.”

During the 1970s, big property developers saw the potential for expansion in what had been the largest fruit market in the world. Just a stone’s throw from the old City of London walls, Big Business was looking to expand east into Spitalfields. They cared not a button for the fine architecture and mouldings, which had sat for two centuries virtually untouched by the successions of immigrants too poor to notice their surroundings, and prepared to flatten the lot.

In the nick of time, a small group of concerned architecture-lovers decided to try to save the area—a unique group of unaltered buildings with a curious and exotic history—by putting themselves physically between the first house, 5-7 Elder Street, and the wrecking ball. In the time the eviction process took to go through the courts, the group played its secret ace—inviting that heavyweight champion of architecture preservation, Sir John Betjeman, to tea. Through him the eyes of the country were opened to the fragile beauty of Spitalfields.

Legal delays enabled the group to negotiate the sale of the house to the newly formed not-for-profit Spitalfields Trust, and gently restore it for sale to sympathetic new owners. Over the next 30 years more than 70 extraordinary houses were saved in a few small streets, and this tiny jewel box of an area has gone from being a bunch of worn-down warehouses to a highly desirable location.

Spitalfields has always been just outside old London’s ancient city walls, a place of refuge for the poor and dispossessed. In the grounds of the long-lost medieval hospital of St. Mary Spital, an ever-changing succession of immigrants settled, got back on their feet and moved on. It is still one of the most cosmopolitan areas of an already cosmopolitan city.

[caption id="SpitalfieldsRevival_img1" align="aligncenter" width="603"]

SANDRA LAWRENCE

Spitalfields as it is now was really established by Protestant Huguenots seeking refuge from Catholic France in the 17th century. The refugees brought with them nothing but their skills, but those skills, which included exquisite silk-weaving, were in great demand. They swiftly became wealthy and started to build elegant, fashionable, beautiful houses for themselves. Unlike the fabulous homes of the gentry in the West End, these are definitely the dwellings of self-made men. An office or shop might be included on the ground floor, and a glance up at the rooflines, even today, shows the bright, finely glazed garrets of the weaving lofts where the real work went on.

The merchants did not stop at building houses, however. They were building a community. Their chapel (on the corner of Brick Lane and Fournier Street) was so magnificent that Church of England authorities started to get worried—so worried, in fact, that they commissioned Nicholas Hawksmoor to build the even grander Christ Church opposite the market, to put the locals in their place.

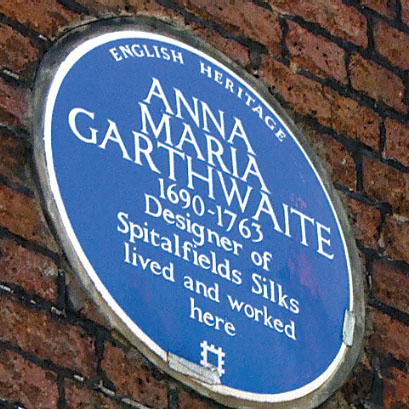

The silk trade died as wars with France came and went, and the once-wealthy merchants became poor themselves. Local pensioner Stan Rondeau is a direct descendant of one of these wealthy merchants, Jean Rondeau, and his family’s fate is typical of the turbulent Huguenots. Rondeau has traced his family back to 1556, and from their fighting for Bonnie Prince Charlie to languishing in debtors’ prison. He learned that his ancestors went from living in the largest house in Wilkes Street and employing the exceptional silk designer Anna Maria Garthwaite (whose fabrics are preserved in the Victoria & Albert) to being flung into debtors’ prison, with one finally forced to seek work as a sexton at Christ Church. “Tracing my family tree helps to bring me in contact with the history of Spitalfields,” he says, breaking from some friendly banter with an American visitor whose ancestor is buried in the crypt and who jokingly swears Rondeau’s ancestor stole the plaque. “You never know who might be able to help you with your search,” he continues.

Following the dispersal of the Huguenots, waves of other immigrants each added layers of their own to the fabric of the area. Irish, Jewish and, most recently, Bengali people have all lived here, but something curious has happened. Or rather, not happened. The magnificent houses built by the weavers remain virtually unchanged, whereas many West-End mansions have been either demolished or altered beyond recognition.

“One of the greatest preservers of architecture is poverty,” explains Leigh-Wood. “These people couldn’t afford to decorate or put in new kitchens or bathrooms. They just got on with sinks and tin baths, put up temporary partitions and nailed hardboard over the fireplaces. As soon as they made money they moved away.”

When the Spitalfields Trust moved in, the area was probably at its nadir. Close to a major station terminus and the hub of a huge 24-hour wholesale market, its streets, once the haunt of Jack the Ripper, were rife with drugs, alcoholism and prostitution. Violent crime, overcrowding and infestation kept fashionable people away. The Spitalfields Trust was able to buy those first few houses cheaply.

The trust follows a plan of conservation rather than restoration, so that both interiors and exteriors are stabilized and loved rather than restored to their original condition. So nail holes around a fireplace where a lump of hardboard was attached—or the gaps where a partition wall was inserted to accommodate yet another family—are treated with as much respect as the fabulous mouldings and carvings. To the Spitalfields Trust, it is all part of history.

Today the fruit and veg market has left town for the M25 motorway. The original market building remains, albeit somewhat overshadowed by a massive glass and concrete office block—but even this has its surprises. Look down to see a glass pavement, under which a medieval charnel house, found when the building’s foundations were dug, can be glimpsed.

The area is one of constant change—a melting pot of ideas and cultures, reflected in the uses to which buildings were put. Nowhere is this starker than in the old Huguenot chapel. Starting life as Calvinist, it was taken over by the Methodists, then the Jews—who turned it into a synagogue. “When the Jews left they wouldn’t sell it to be anything other than a place of worship,” says Leigh-Wood. “So it has become a Muslim mosque. Sadly they don’t have the same love for the building. They’ve ripped out all the internal decorations, including the historic wooden balcony.”

Luckily the Spitalfields Trust happened to be around at the time when all the interiors, including that balcony, were being stripped out. They climbed into the builders’ skips and recovered the pieces, which now wait in storage for a time when the building will have an owner that chooses to restore it. Trust members do a lot of skip-diving. “We save everything we can,” Leigh-Wood affirms. “With our own properties, we act more as an adviser than a police force, though we do pass on houses with covenants to ensure they are properly looked after.”

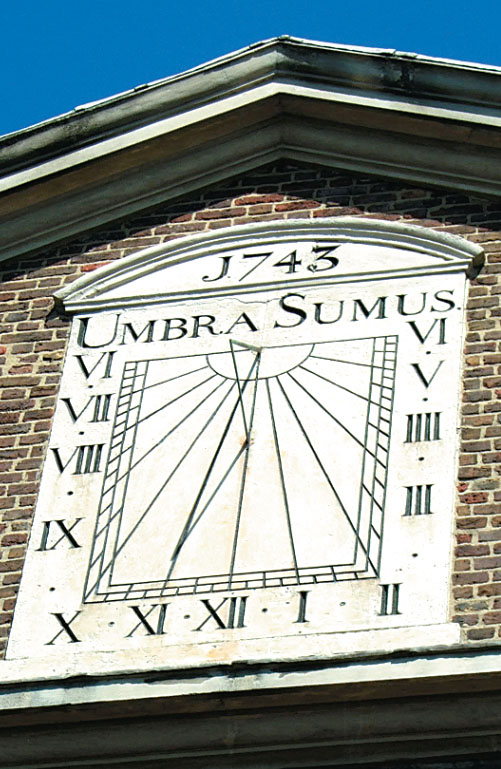

[caption id="SpitalfieldsRevival_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

REBECCA MILLER

The other major church, Hawksmoor’s Christ Church, has seen its share of trauma, too. By 1957 it had fallen into dereliction and was slated for demolition. It was just about saved and turned into a center for alcoholics. Then in an amazing about-face, the very active Friends group raised enough money to restore the exterior. The massive interior—the height of Exeter Cathedral and half the volume of St. Paul’s nave—has just reopened after a multimillion-pound restoration thanks to a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund. The church is once again active in the community. An exquisite building, returned to the way it might have looked in Hawksmoor’s time, it’s well worth a stroll around or, even better, a visit to one of its many concerts.

It’s unlikely the properties won’t be looked after. The dynamics of the area have changed. The City has encroached upon this little area once just outside its walls, and a new atmosphere has emerged. The people moving in now know exactly what they are getting—and are prepared to pay for it. “Not so long ago, you could buy a house for £15,000. Now they go for a million—over 2 million if restored,” says Leigh-Wood.

The colorful and eccentric Dennis Severs has left London with its most curious house. In the 1960s, Severs, originally hailing from Southern California, decided he no longer wanted to live in the 20th century—“a fascinating place to visit,” he famously quipped, “but surely nobody would want to live in it?”

Severs bought 18 Folgate Street, removed the electricity and the plumbing, and started work to re-create the 18th century. He invented himself a Huguenot family and built them not only a house, but also an entire history. Haunting flea markets and antique shops, Severs decorated the house—and lived in it—so that it became part period home, part art-installation, all theater. Every room is set up as though its inhabitants have just left it and are about to return any minute. Clean it is not—the sheets are rumpled from a night’s sleep and there is fresh piss in the pot. In the attic the cobwebs are nearly as persistent as the drip from a distant gutter. Half-eaten lunch lies on a plate; an elaborate tray of jellies waits to be tucked into. Some rooms are so dark it’s necessary to stand in them for several minutes to grow accustomed to the light from a single lanthorn. Children’s toys litter the stairs, and visitors need to mind their heads and keep their elbows in as they go round in tiny, silent groups. But few leave unaffected by this cabinet of curiosities, the closest thing to owning a time machine.

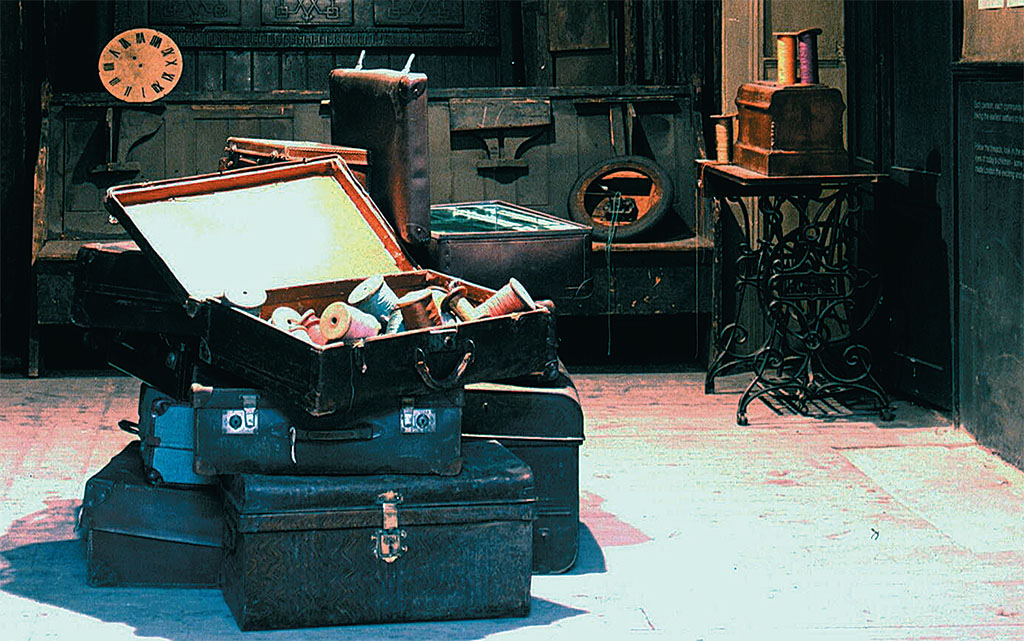

[caption id="SpitalfieldsRevival_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JOEL PIKE/19 PRINCELET STREET

Exploring Spitalfields

- WALKING TOUR: www.cityoflondon.gov.uk. Site search: “On Your Feet” and “Spitalfields Walk”

- DENNIS SEVERS HOUSE: www.dennissevershouse.co.uk

- CHRIST CHURCH: Open on Tuesdays, when Stan Rondeau is often to be found. www.christchurchspitalfields.org

- 19 PRINCELET STREET: www.19princeletstreet.org.uk

[caption id="SpitalfieldsRevival_img4" align="aligncenter" width="409"]

[caption id="SpitalfieldsRevival_img5" align="aligncenter" width="407"]

[caption id="SpitalfieldsRevival_img6" align="aligncenter" width="501"]

SANDRA LAWRENCE

The Spitalfields Trust can’t do much more in the area with house prices now way beyond its reach. It is, in many ways, a victim of its own success. All it can do is lobby for listed status on the more modest Georgian buildings that even now remain unprotected, and to fight a never-ending battle against City encroachment.

It’s just possible, though, that all the area’s secrets have not been revealed. Some years ago another amazing discovery was made at No. 19 Princelet Street. A seemingly ordinary 1719 weaver’s housefront opened out at the back to a dusty, cobwebby secret place—an entire Jewish synagogue, built quietly in the back garden in 1869. The synagogue, complete with slender barley-sugar columns supporting a gallery and memorials to worshippers, still had its original chandeliers and some of its furniture; the door had just been locked behind it and the place forgotten. Eerily lit by a stained-glass roof, and containing a small, thoughtful exhibition exploring immigration, as a piece of architecture it is remarkable. As a piece of human history it is exceptional. It tells the poignant story of human suffering brought by generations of being displaced. The place is desperate for funds and run by volunteers; thus is only rarely open, but it is worth checking the Web site and making a special effort to see this beautiful, fragile and deeply affecting museum.

The only way to really experience Spitalfields’ uniqueness is to walk around, breathing in the last gasps of Huguenot splendor saved from the brink by people who care. The area is tight; the streets narrow and cobbled, which makes walking easy. Remembering to look both up at the rows of weavers’ garrets and down into gloomy basements is as important as the shabby delights of shuttered windows, elaborate door gables and faded writing announcing the professions of generations of inhabitants. Some of the tiniest alleys, lit by ancient streetlamps, are pedestrian-only, now full of smart boutiques and dinky lunchtime retreats—darkened wine bars, historic pubs and sandwich bars. There are also plenty of eateries around Spitalfields market, plus unusual shops selling everything from corsetry to home wares, antiques to modern art.

Unfortunately, a walk through Spitalfields is sometimes confused with hideous tourist-trap Jack the Ripper tours conducted by spotty students in top hats and cloaks, milking the gory side of the area’s history. Although there are some excellent “proper” guided tours, Gareth Harris, one of the trustees of the Spitalfields Trust, wrote an excellent self-guided walking tour some years ago for the City of London, which takes in the major sights and sounds of the area. The Web site is unwieldy, but it offers a wonderful tour titled “On Your Feet.” Spitalfields is finally back on the map.

Comments