[caption id="SportsmanLadyKillerRenaissancePrince_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="567"]

On the 500th anniversary of the accession of Henry VIII, the vestiges of England’s famous Tudor king abound

When Henry VIII came to the throne of England in 1509, a Venetian observer remarked with rare foresight, “for the future, the whole world will talk of him.”

Now, 500 years after Bluff King Hal’s accession, commemorative events have dominated the English landscape—celebrating the handsome Renaissance prince, the “Father of the English Navy,” the sovereign who helped transform England from medieval kingdom to modern state.

He was the gilded youth who morphed into the bloated colossus staring from portraits in such stately venues as Hever Castle in Kent; the faithful Roman Catholic who broke with Rome, destroyed England’s monasteries and became head of a new Church of England; the ruthless dynast who married and murdered in baleful pursuit of a legitimate male heir. It’s easy to roll such contradictory images into a caricature of some magnificent monster.

Truth is, Henry is arguably England’s most important ruler because of the increased status and power he brought to the monarchy and the kingdom.

He was the first English king to adopt the salutation “Your Majesty” in place of the more customary “Your Highness” or ”Your Grace.” Perhaps the pursuit of majesty is the key to unlocking the enigma of his character and his legacies. It certainly opens the doors to some of the country’s most impressive heritage.

Young Hal was originally groomed for Church rather than the Crown, but when his elder brother Arthur died of consumption in 1502, 10-year-old Henry became heir apparent. He inherited the throne shortly before his 18th birthday. His father, Henry VII, had brought the Tudors to power by right of conquest at Bosworth in 1485 and had worked hard to unite England after the dynastic strife of the Wars of the Roses. He successfully left his son a largely unified country with strong finances.

So everything began well for Henry VIII. He followed his father’s dying wish and married Arthur’s widow, Katherine of Aragon, to keep alive the alliance by marriage with Spain—Katherine assured the world her marriage with Arthur had never been consummated. Nature was on Henry’s side, too: Tall, handsome, athletic, affable, he was accomplished in languages, music, theology and humanist learning, and fascinated by new technologies, architecture and astronomy. He seemed the very ideal of a Renaissance prince.

[caption id="SportsmanLadyKillerRenaissancePrince_img1" align="aligncenter" width="940"]

CASTLE HOWARD, UK/THE BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY INTERNATIONAL

‘TALL, HANDSOME, ATHLETIC, HENRY WAS ACCOMPLISHED IN LANGUAGES, MUSIC, THEOLOGY AND HUMANIST LEARNING’

Where Henry VII had been reserved, diligent and parsimonious, Henry VIII was fun loving. In the early years of his reign he left affairs of state to ministers, preferring to sport with his clique of dashing young companions, the “minions.” You can still wander in some of his favorite hunting venues—he established London’s Hyde Park and St James’ Park. Courtly jousts, at which he excelled, became the talk of Europe, and his resplendent annual progresses endeared him to his countrymen. Under the Tudors, pageantry and ceremony reached new heights, a peacock endorsement of their authority. Henry walked the walk, dressed to impress and amassed more jewelry than any other English king. Here was majesty—grandeur, dignity and power—in full youthful vigor; tangible proofs of sovereign right and might, by birth not battle.

To get an idea of the sumptuous levels of Henry’s entertainment (he spent around a third of the royal income on court expenses and swiftly emptied his father’s coffers), pay a visit to the cavernous Tudor Kitchens at Hampton Court Palace, the most extensive surviving 16th-century kitchens in Europe. Henry enlarged them in 1529 to occupy over 50 rooms, which, in their heyday, were staffed by 200 people providing meals for 800 members of court. Much has vanished, but monthly live Tudor cookery sessions will give you a feel for the feasts Henry served to dazzle visitors.

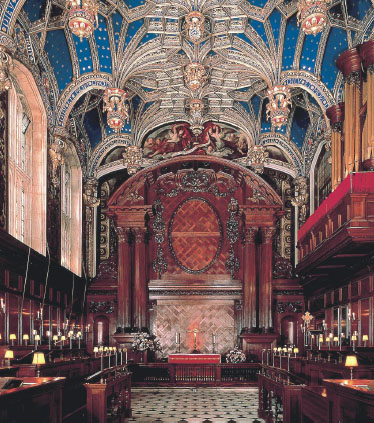

The king had coveted—and duly received—Hampton Court Palace from his lord chancellor, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, in 1528 and spent £62,000 (well over £18 million today) on rebuilding and improvements. His lavish private rooms were demolished in the early 18th century, but the two most magnificent public rooms, the Great Hall and Chapel Royal with Henry’s superb vaulted ceiling, still trumpet his grandeur. At Hampton Court you’ll also find some of the most important examples of his renowned tapestry collection.

Henry inherited, acquired and built more than 70 residences—another record for an English sovereign—to provide the glorious stage for his majesty. Nonsuch Palace in Surrey, the most stunning example of his architectural propaganda, is sadly long vanished, but elsewhere there’s plenty to admire: He built redbrick St. James’s Palace, London, added the Maiden’s Tower and banqueting hall to Leeds Castle near Maidstone, and St. George’s Chapel was completed under his auspices at Windsor Castle. He furnished in style and was essentially the first English monarch to collect art in the modern sense: His paintings are at the core of today’s priceless Royal Collection. Little wonder that Henry twice devalued the coinage to finance his prodigious lifestyle as well as his international ambitions.

[caption id="SportsmanLadyKillerRenaissancePrince_img2" align="aligncenter" width="325"]

BRITAINONVIEW

The king took much greater interest in details of state as he matured, and he made shrewd administrative appointments: first Thomas Wolsey, then Thomas Cromwell. He hankered to play a central role on the European stage, alternating diplomacy with martial exploits, though little of lasting effect was achieved. Having joined the Holy League against England’s old enemy, France, he led victories against the French at Thérouanne, Tournai and the Battle of the Spurs in 1513, the same year English forces under Thomas Howard beat off an invasion by the Scots at the Battle of Flodden.

Seven years later, Henry the diplomat met King Francis of France for a summit near Calais, known as the Field of the Cloth of Gold for its breathtaking displays of extravagance. Francis beat Henry at a friendly game of arm wrestling; Henry beat Francis at archery. The resulting peace treaty was short-lived.

[caption id="SportsmanLadyKillerRenaissancePrince_img3" align="aligncenter" width="780"]

BRITAINONVIEW

[caption id="SportsmanLadyKillerRenaissancePrince_img4" align="aligncenter" width="374"]

HISTORIC ROYAL PALACES/NEWSTREAM.CO.UK

[caption id="SportsmanLadyKillerRenaissancePrince_img5" align="aligncenter" width="372"]

HISTORIC ROYAL PALACES/NEWSTREAM.CO.UK

‘WITHOUT A LEGITIMATE MALE HEIR,HENRY’S MAJESTY WAS A BRIGHT BUT HOLLOW CARAPACE, A DYNASTY GOING NOWHERE’

[caption id="SportsmanLadyKillerRenaissancePrince_img6" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

BRITAINONVIEW

Henry was a conscientious Roman Catholic, so when Martin Luther launched his series of attacks on the papacy and Catholic Church, the king replied with his Defence of the Seven Sacraments. It became a bestseller throughout Europe, and the Pope rewarded him in 1521 with the title Fidei Defensor, Defender of the Faith. Events would soon prove the lofty title a singularly inappropriate accolade.

For there was one aspect of Henry’s kingly brief that remained unfulfilled: a legitimate male heir. Without that, the glorious projection of his majesty was a bright but hollow carapace, the mark of a dynasty that was going nowhere. Queen Katherine had borne a son, Henry, in 1511, but the child had died after seven weeks. Only a daughter, Mary, survived from half a dozen births, and a female succession was unthinkable.

By 1526, when Katherine had turned 40, Henry knew prospects were bleak. The fact that he began to groom as his heir his illegitimate son Henry Fitzroy, born to Elizabeth Blount in 1519, gives a measure of his desperation. (Fitzroy later died, probably of tuberculosis, in 1536.)

Personal, political and wider theological forces all got sucked into the vortex of the King’s “Great Matter.” Increasingly convinced that marriage to his brother’s wife had been wrong (why else was there no male heir?) Henry sought in vain for a papal annulment. The reforming zeal of Lutheranism that the king had so recently opposed suddenly seemed more in tune with his own resentments against Rome. Moreover, he had fallen passionately in love with one of his wife’s maids of honor, Anne Boleyn.

Encouraged by his adviser Thomas Cromwell, Henry set in motion stage by stage the country’s break with Rome. The Act of Supremacy in 1534 enshrined in law the sovereign’s status as supreme head of a separate Church of England. In fact, Henry had already appointed his own archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, who had obligingly annulled his first marriage, and he had wed Anne Boleyn. Majesty had taken on another dimension.

Henry’s Reformation in England brought many casualties, including Sir Thomas More and Bishop John Fisher, executed for refusing to acknowledge the king’s new ecclesiastical authority. Royal investigations into the country’s monasteries—and the ferocity of their dissolution from 1536 on—smacked of political motive and greed. Visit the haunting ruins—from Rievaulx Abbey in Yorkshire to Tintern Abbey in Wales—and the picture of a Renaissance prince turned cultural vandal sends a shudder through the bones.

[caption id="SportsmanLadyKillerRenaissancePrince_img7" align="aligncenter" width="460"]

BILL BISHOP/MARY ROSE TRUST

[caption id="SportsmanLadyKillerRenaissancePrince_img8" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

THE MARY ROSE TRUST

[caption id="SportsmanLadyKillerRenaissancePrince_img9" align="aligncenter" width="192"]

Some religious houses morphed into gentrified residences, and Henry did found cathedrals that saved the monastic churches like Bristol, Gloucester and Westminster. But the Dissolution showed him at his worst.

Anne Boleyn, of course, failed to produce a male heir, lost her head at the Tower of London and was replaced by Jane Seymour. Seymour at least proved dependable, bearing a prince, Edward, in 1537; though she died in the process. That same year, ever attuned to the importance of propaganda, Henry had commissioned a mural of the Tudor dynasty from Hans Holbein the Younger, the King’s Painter. The vast work was unfortunately lost when fire destroyed Whitehall Palace in 1698, but it has been hailed as the first English state portrait. Henry had set another enduring trend.

The king’s marital merry-go-round continued apace, with the 1540 political match to Anne of Cleves that was annulled after six months because Henry disliked the “Flanders Mare.” (Cromwell, who had been instrumental in arranging the liaison, lost his head.) Young Katherine Howard cuckolded the king and was executed in 1542 after little more than 18 months of marriage. Then from 1543 Katherine Parr provided the companionship that would fill the final years of Henry’s life.

Throughout this time Henry had continued to play the international scene and, following his break with Rome, invasion from Catholic Europe by France and Spain was a real threat. Driven by a passion for naval technology and ships, Henry established dockyards at Woolwich and Deptford, and the naval base at Chatham began to develop. During his reign he would build 46 warships and 13 galleys, buy 26 vessels and capture 13 more. His was the world’s best navy.

For the most tangible link with Henry’s fleet, visit Portsmouth, where his favorite warship, Mary Rose, was built from 1509 to 1511. One of a new breed of warships, it carried heavy guns below deck and fired broadsides. But its successful battle career came to an abrupt end July 19, 1545, when it sank in an accident while it was engaged against the French fleet off Portsmouth as Henry watched horrified from Southsea.

The English won the skirmish, but Mary Rose remained buried in the silt of the Solent until 1982, when it was raised and its wreck deposited at Portsmouth’s Historic Dockyard for all to view. In the museum you can pore over many of the 20,000-plus artifacts that have been recovered: Arrows, longbows, navigational equipment and Henrician cast bronze guns; tableware, clothes and a gruesome barber-surgeon’s chest—all attest to Tudor life at sea.

Also take a tour of the chain of coastal fortresses Henry hastily built from 1539 to fend off invasion, from Pendennis and St. Mawes in Cornwall to Walmer and Deal in Kent. They were at the cutting edge of military architecture.

‘THE LEGACIES OF HENRY’S REIGN AND THE PURSUIT OF MAJESTY THAT THREADED THEM TOGETHER ARE DAZZLING’

[caption id="SportsmanLadyKillerRenaissancePrince_img10" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

BRITAINONVIEW

At Deal, for example, squat multiple bastions cluster around a keep, their low walls minimizing the target available to artillery. The tiered design allowed for 66 guns to be mounted and for close-quarter defense that made the castle virtually impregnable.

Although the fortresses weren’t tested in Henry’s time, they stood the country in good defensive stead in years to come. So, too, his navy left the country poised for the Elizabethan age of exploration and laid the foundations for future naval dominance.

Henry’s latter years were overshadowed by financially draining wars with France and skirmishes with Scotland; his health was failing, too. As early as 1528, he had begun to suffer recurrent headaches—possibly caused by jousting injuries—and painful leg sores thought to have been osteomyelitis. In middle age he became obese, with a bursting waistline of 54 inches. And with Wolsey, More and Cromwell gone, he trusted nobody and retreated into increasing personal isolation. He was growing to be like his father.

Who knows what fears, disappointments and betrayals weighed on his conscience as, aged 55, he lay on his deathbed in the early hours of January 28, 1547. Entreated by Archbishop Cranmer to give a sign that he died in the faith of Christ, Henry, a Catholic despite the momentous changes he had unleashed, “did wring his hand in his as hard as he could.” He was laid to rest in St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, with Jane Seymour.

There’s no doubt that bodies and wreckage lay strewn in the aftermath of Henry’s reign, from the corpses of Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard at the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula, Tower of London, to the accusing skeletons of the monasteries. Some of his deeds are unpardonable. Yet the legacies of his reign and the pursuit of majesty that threaded them together are undeniably dazzling.

He embraced Renaissance culture and ensured that England wasn’t consigned to a backwater. He brought a new sense of national consciousness and, steering a singular course through the choppy waters of the Reformation, created a kingdom that owed no allegiance to any outside authority. Through the 1536 Act of Union, he officially annexed Wales to England, and in 1542 he declared himself king rather than lord of Ireland. He punched above his weight on the international stage and left the country in financial debt, but he raised the monarchy to new heights. He could rule as a despot, yet, rarely, he wielded that power without destroying himself.

Tudor Times Still Live!

- Coastal castles Tour Henry VIII’s coastal defenses at Deal and Walmer Castles in Kent, as well as Pendennis and St. Mawes Castles in Cornwall. www.english-heritage.org.uk

-

Hampton Court Palace, East Molesey, Surrey Celebrations of the 500th anniversary of Henry’s accession to the throne include the re-creation of a heraldic Tudor garden in Chapel Court, inspired by his 16th-century Privy Gardens.

www.hrp.org.uk/HamptonCourtPalace - Hever Castle, Edenbridge, Kent The childhood home of Anne Boleyn boasts many intriguing Tudor artifacts. A summer of jousting tournaments and Tudor revelries mark Henry’s anniversary. www.hever-castle.co.uk

-

Leeds Castle, near Maidstone, Kent Henry inherited Leeds Castle on his accession. Its ownership in the 15th century by Catherine de Valois, widow of Henry V, also provides a piquant tie: Catherine’s subsequent marriage to Owen Tudor is at the root of the Tudor dynasty; their son Edmund fathered Henry VII.

www.leeds-castle.com -

Mary Rose, Portsmouth Historic Dockyard, Hampshire

Raised remains of Mary Rose, plus an unrivaled trove of Tudor maritime artifacts. www.maryrose.org - Tower of London Find tombs of many of Henry’s illustrious victims in the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula. An exhibition in the White Tower, “Henry VIII: Dressed to Kill” (to October 31), explores the themes Henry the King, Henry the Warrior and Henry the Sportsman. www.hrp.org.uk/toweroflondon

[caption id="SportsmanLadyKillerRenaissancePrince_img11" align="alignright" width="164"]

[caption id="SportsmanLadyKillerRenaissancePrince_img12" align="aligncenter" width="353"]

123RF/STEPHEN FINN

Comments