[caption id="StreetlightsofLondon_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

[caption id="StreetlightsofLondon_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

BRITAINONVIEW/PAWEL LIBERA

St. Paul’s and the Museum of London

ST. PAUL’S CATHEDRAL, in the London neighborhood known as “the City,” remains the linchpin of this area where it has stood for centuries. One of the best views of the cathedral reaches out to visitors as they walk toward it over the Millennium Bridge from Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre and the Tate Modern Museum. Though construction in recent decades has interfered with its full view from various locations, Christopher Wren’s magnificent structure with its familiar dome, which took 35 years to complete, still peeks out from streets and corners when one least expects it.

Successful plans were recently implemented to open up the piazza around St. Paul’s Cathedral so that the space is more in keeping with how it looked in 1697, when the first service was held at the new cathedral, built to replace the one that was destroyed by fire some three decades earlier. The result is the new Paternoster Courtyard with its brilliant white stone that gleams on a sunny day and surrounds the north facade of the cathedral.

A massive stone arch leads into the courtyard, which is adorned with a huge sun clock showing the position of the sun throughout the months of the year. In the middle of the space, an obelisk soars upward, and several large sculptures are scattered around the area. Various restaurants and cafes are located in the Paternoster Courtyard, and it has once again become a meeting place for people.

In the shadow of St. Paul’s are three grand townhouses designed by Wren that are now the homes of the canons of the cathedral. The houses are at Nos. 1, 2 and 3 Amen Court, which is tucked behind the Old Bailey, the still active criminal courthouse that was erected in 1907 on the site of the infamous Newgate Prison demolished in 1902.

Across the road from the Old Bailey is the Magpie and Stumps, a pub with decent food that continues to serve customers though it has discontinued the “execution breakfasts” it served until 1868, when public hangings ceased outside the prison.

The newspaper industry used to dominate this part of London. Fleet Street, just outside St. Paul’s west steps, was equated with reporters and ink. All the papers have since relocated to the renovated Docklands to the east. Also, this area has long had connections with business and finance, and the Royal Stock Exchange and Bank of England are within walking distance. While the enclosed protective borders of this neighborhood no longer exist, just beyond St. Paul’s Cathedral names like Aldersgate, Cripple-gate and Moorgate remain as reminders of its past.

[caption id="StreetlightsofLondon_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

©MARTYN VICKERY/ALAMY

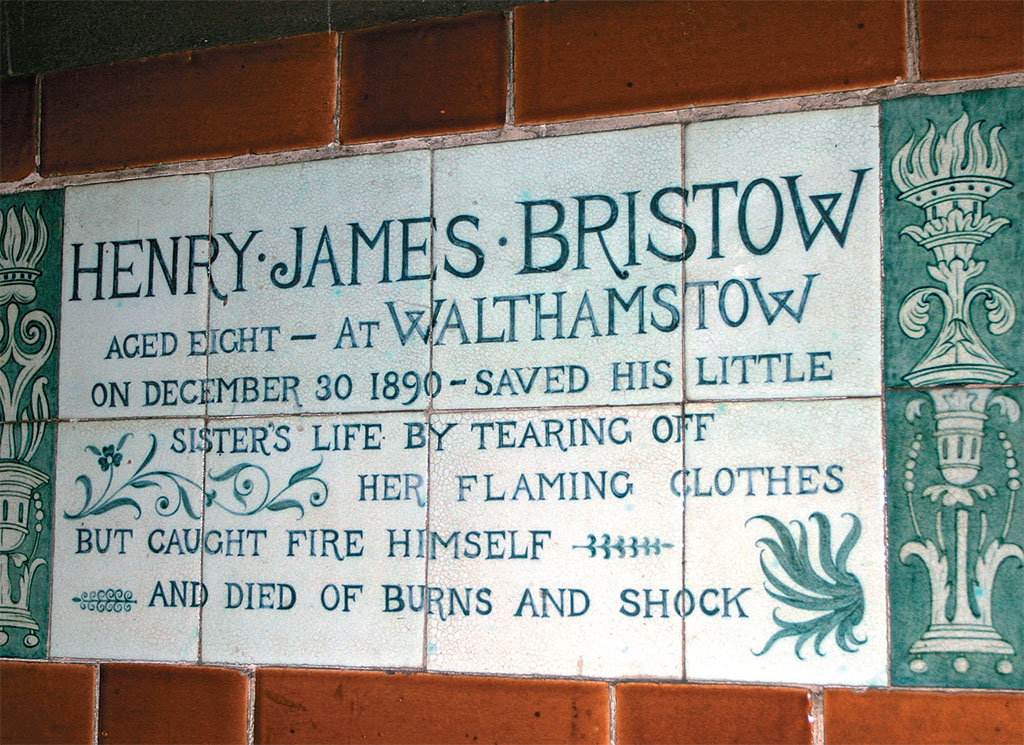

A little-known retreat is Postman’s Park, a green space with a fountain and benches situated between King Edward Street and Angel Street, just up the road from the cathedral. The park acquired its name because of its popularity with workers from the now defunct General Post Office nearby. G.F. Watts (1817-1904), a Victorian painter and philanthropist, created the park with his own money in 1887 to honor the “heroic men and women” who had given their lives to save others. Numerous glazed tiles mounted along the park’s enclosed walls pay touching tribute to individual acts of bravery, making it a unique oasis in a busy part of town.

A hop and a skip from St. Paul’s Cathedral is the Barbican Center, built in the early 1970s. The Barbican is constructed like a fortress above the busy streets on multiple levels. There are pedestrian walkways throughout the complex, connecting its many residential buildings and an arts center that contains a multiscreen cinema, two theaters and a concert hall—home to the London Symphony Orchestra.

The short walk from the cathedral to the Barbican Center is a well-preserved step back in time. St. Bartholomew’s Hospital and St. Bartholomew’s the Greater Church, dating to medieval times, exist side by side, while the beautifully ornate buildings of Smithfield are just across the square on Charterhouse Street. Meat has been bought and sold here for more than 800 years, making it one of the oldest markets in London.

Among the newer buildings in this ancient neighborhood is the Museum of London, created at the same time as the Barbican Center and opened to the public in 1976. This fascinating place details the history of the great city from the Paleolithic Age to the present day and is the largest urban history museum in the world. It consists of a series of galleries depicting London’s history in chronological order. The objects on display there include such diverse items as archaeological finds, photographs, shop fronts, archival film and video, jewelry, clothing and bus tickets, with some of the oldest items dating back more than half a million years. It covers the social and economic history of the city and charts its urban development.

Currently the museum, which is open free of charge, is undergoing a long-term program to overhaul its collections, and it has installed contemporary interactive exhibitions. The lower galleries will be closed in February 2007 for a period of time. The upper galleries, which have already been updated and include the prehistoric exhibit known as “London Before London,” remain open. These upper galleries have many interesting displays, including prehistoric weapons found in the Thames that young visitors seem to especially enjoy.

The Victorian Walk is one of the most popular parts of the Museum of London. Its multitude of shop fronts include a grocer, stationer, tailor, tobacconist and barber, and is a vivid reminder of a time that has all but vanished. Also on display is the Lord Mayor of London’s ornate state coach used on ceremonial occasions and dating back a number of centuries. In another part of the museum, an audio/video display reveals the eyewitness account by the diarist Samuel Pepys of the Great Fire of 1666 that swooped through and destroyed so much of this area.

The Museum of London overlooks the remains of the Roman city wall just outside its door. The ancient wall still stands as a reminder of what was once the border for the old part of London long known as the City. How fitting that a museum that walks visitors through time and presents the everyday lives of ordinary Londoners against the story of the City itself has this piece of history without to welcome those within.

Many of the Wren churches have lunchtime concerts on weekdays, so classical music at St. Anne and St. Agnes, St. Vedast or St. Stephen Walbrook is always close by. Like other London neighborhoods, this area, one of the oldest in London, is undergoing change while still retaining a number of historic buildings. It offers exceptionally intimate and intriguing glimpses of quiet lanes and hidden alleys that represent a visual time capsule, with layer after layer revealing itself as visitors explore it on foot. Once again, London’s history can be felt by walking its streets.

Comments