Holborn and Sir John Soane’s Museum

[caption id="StreetlightsofLondon_img1" align="aligncenter" width="80"]

[caption id="StreetlightsofLondon_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

MASSIMO LISTRI/CORBIS

CHARLES DICKENS knew the London neighborhood of Holborn well, often using its streets as a setting in his classic novels. For visitors today in this part of London, the neighborhood’s centuriesold diminutive shops, quaint narrow streets and illustrious gardens and squares continue to hold their places among the rather ordinary new buildings.

Holborn, is a principal central London thoroughfare. It is home to Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London’s largest formal public square, a 12-acre site laid out by the famous architect Inigo Jones (see story, P. 26) in the 17th century. With its strong association to the legal profession, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, once the most fashionable square in London, lies across Kingsway, just beyond the theaters and restaurants of Covent Garden. The neighborhood has traditionally been home to the Inns of Court, ancient law centers that for centuries have symbolized the role of law as mediator in the power battle between the City and Westminster. Many of the buildings in the area survived the Great Fire of 1666, including the beautiful black-and-white timber-framed facade of the Staple Inn, farther along on High Holborn.

[caption id="StreetlightsofLondon_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

NEIL SETCHFIELD/ALAMY

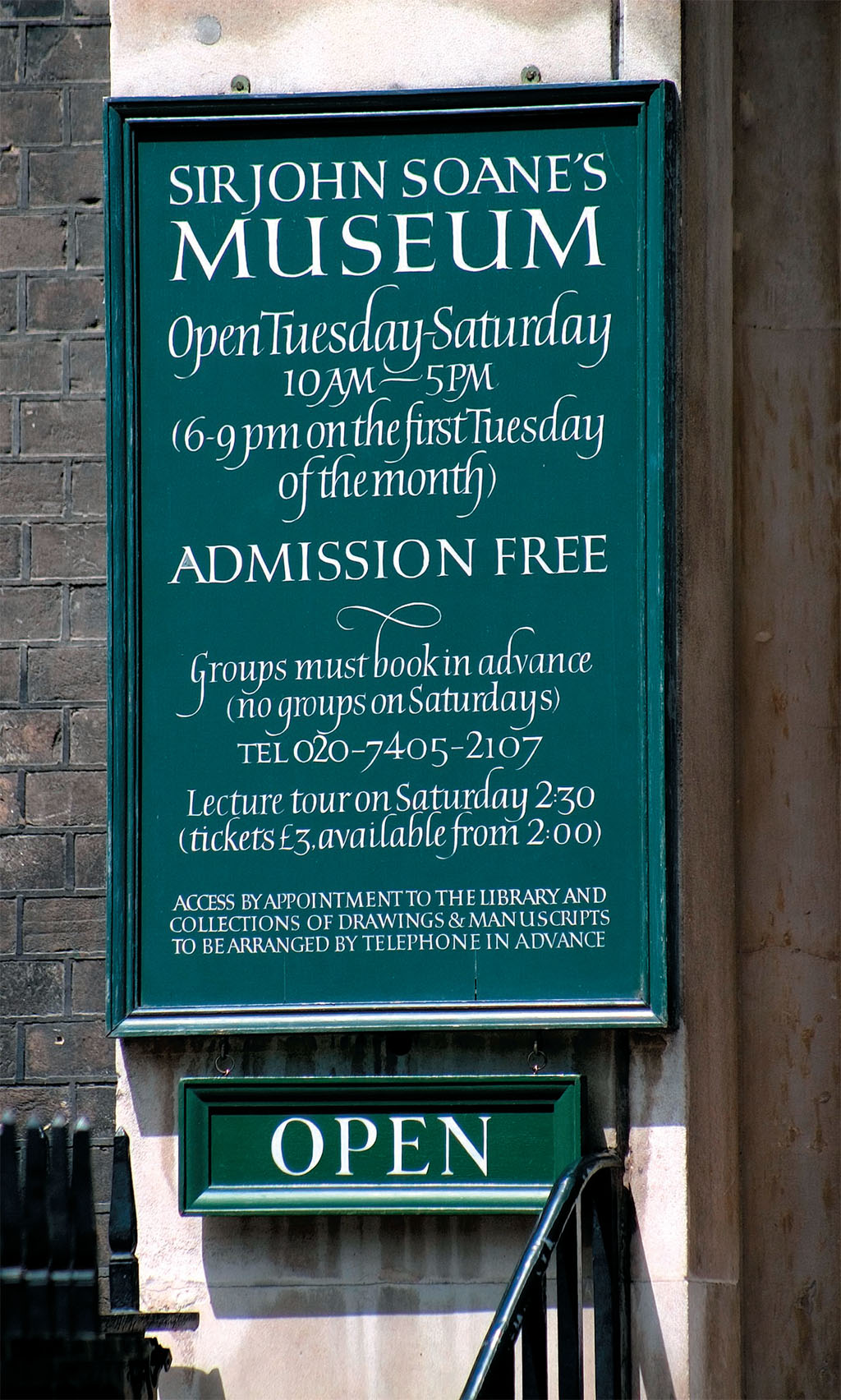

Overlooking Lincoln’s Inn Fields on the north side is Sir John Soane’s Museum. Sir John was one of England’s greatest architects, responsible for the Bank of England and the Dulwich Picture Gallery. Four years before he died in 1837, he established, his home at No. 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields as a museum that would be open to the public, with the stipulation that it be kept “as nearly as possible in the state in which he shall leave it.”

The first rooms entered in the museum, according to the plan Sir John wanted visitors to follow, are the dining room and library. These are painted in a Pompeian red, probably because of wall plasters he observed when visiting excavation sites in Pompeii. Many of Soane’s 7,000 books are on the shelves here. In Soane’s small study and dressing room, a collection of antique marble fragments that he acquired in 1816. A window looks out into the Monument Court to a vast collection of sculptures and antiquities. The breakfast room contains a mirrored vaulted ceiling, and the table is set with pieces from Mrs. Soane’s tea service.

The many grand staircases and rooms graced by avenues of light add to the house’s aura. Throughout the house, Soane used mirrors above bookcases and behind works of art to create the illusion of more space.

Some of the most notable items in the Soane collection are the first three folio editions of Shakespeare, printed in 1623. At the curve of the staircase leading to the first floor is the Shakespeare Recess, where there is a cast of an original bust of Shakespeare as well as paintings illustrating scenes from his plays.

The museum’s extensive collection of paintings also includes works by many well-known artists such as Reynolds, Turner and Canaletto. The high-ceilinged picture room, lit from above, features 12 William Hogarth paintings and engravings, each projecting a moral lesson. From 1733 to 1735, Hogarth completed the eight works that make up The Rake’s Progress, about the rise and fall of one Tom Rakewell, and in 1754 he finished the museum’s four large works of political satire known as The Election.

From Lincoln’s Inn Fields, High Holborn leads to Gray’s Inn and its gardens, known as the Walks. At the far end of the Walks is Jockeys Fields and Bedford Row, lined with well-preserved 18th-century houses. Nestled just off Theobald’s Road is Red Lion Square, where the visitor will find stately old trees, an outdoor café.

Tucked away at one of the far corners of Red Lion Square is historic Conway Hall, named after Moncure Daniel Conway (1832-1907), an American antislavery advocate, and biographer of Thomas Paine. Conway Hall is the home of the London Chamber Music Society, which hosts concerts on Sunday evenings. These concerts, the world’s longest-running continuous series of chamber music performances, began in 1879 in Whitechapel in London’s East End and then relocated to the South Place Chapel near Finsbury Park. When Conway Hall opened in 1929, the concerts found a permanent home in a hall that was built especially for chamber music.

Certainly Sir John Soane’s Museum is sufficient reason to visit Holborn. When the museum was opened in Soane’s lifetime, visitors were not admitted in “wet or dirty weather,” though that is not the case today.

On the surface, Holborn does not, nor did it ever, offer the main attractions linked with the capital city, but it does yield glimpses of how a neighborhood lives with its evolving history. Wrote Charles Dickens Jr. in Dickens’s Dictionary of London in 1879: “Until the last few years, the row of houses…formed one of the most curious bits of old London remaining. The line of houses, however, still remaining at this point…are still well worth seeing, as being by far the most perfect specimens of old street architecture, with its wooden beams and projecting upper storeys, remaining in London.”

Comments