The Criterion Theatre, Piccadilly Circus, W1

[caption id="The39Steps_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

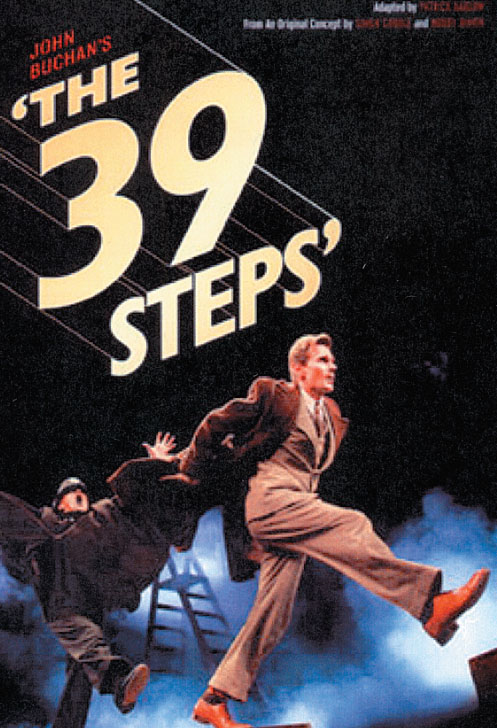

THE CLASSIC ALFRED HITCHCOCK FILM of John Buchan’s thriller is a creepy affair indeed, catapulting an innocent 1930s theatergoer into a web of intrigue which sees him escaping across the roof of a moving train, crossing a deserted moor and finally clinging to the Forth Bridge for his very life.

That a theater presentation could not only turn this into broad comedy, including all the stunts (more or less) from the film—the biplane crash is a particular favorite—and a cameo from The Man Himself, but also do it with a cast of four, marks this particular production as a truly British comedy setpiece. From humble beginnings at The Tricycle Theatre in Kilburn, North London, this production has not only transferred to one of the most beautiful theaters in the West End, but also has just won the Olivier Award for Best New Comedy.

Writer Patrick Barlow has been familiar to British audiences as the guiding light of The National Theatre of Brent for the past 27 years. He has never fought shy of the epic form. Zulu, The Charge of the Light Brigade and Wagner’s Ring Cycle are just a handful of the productions that did not allow mere lack of space, sets, cast or cash to prevent creation of truly extraordinary theatrical experiences, often with a cast of as little as two managing to tell the entire history of the French Revolution or to re-create the Black Hole of Calcutta.

[caption id="The39Steps_img2" align="aligncenter" width="497"]

By comparison, The 39 Steps is positively lavish, with a gigantic cast of four portraying merely 150 rather than the usual thousands of characters fielded by the company. Buchan’s Ordinary Joe-hero, Richard Hannay, is portrayed by one of the four, a fabulously dapper Charles Edwards, his performance so perfectly 1930s that it’s almost impossible to imagine the actor offstage in the modern world. He plays Hannay totally straight, in a crisp, charming and all-at-sea manner that only a certain kind of upper-class chap caught in a spot of bother can have. An island of puzzled serenity amid the chaos that is the rest of the cast trying to play everyone else, Edwards gives away only an occasional raised eyebrow when his calm is ruffled at moments of high tension.

The two mysterious, beautiful women who cross his path are played to perfection by Catherine McCormack, retaining that eerily erotic moment when Hannay and his mysterious blonde are handcuffed together for the night as an extraordinary combination of collar-heating steam and snicker-worthy, puerile farce.

That leaves the other 147 characters to be portrayed by two complete lunatics, Rupert Degas and Simon Gregor, whose jaw-dropping stunts at breakneck speed make them the real stars of the show. This exhausting pair give the double-act treatment to everyone from a cheery-chappie milkman, a crazed Scottish farmer, an eccentric elderly couple, a pair of policemen (played by one of them, talking to himself) a pair of Max-Miller-esque underwear salesmen, some truly memorable women (including a cockney charlady and a sinister Scottish housekeeper) and a remarkable election chairman whose mumbled speech is inspired.

The stunts use ingenuity rather than expensive props or modern technology. Basic items—stepladders, chairs and suitcases, recreating a moving train, a foggy moor, an old-fashioned car and The Forth Bridge—have a simplicity that frames the mayhem around them with an eloquence that fancy sets would lose.

There is nothing cutting-edge about this production of The 39 Steps, but also nothing arch or knowing. It is precisely that non-technological, old-fashioned style that allows its creators to both parody and relish a 1930s classic that they clearly adore.

Sandra Lawrence

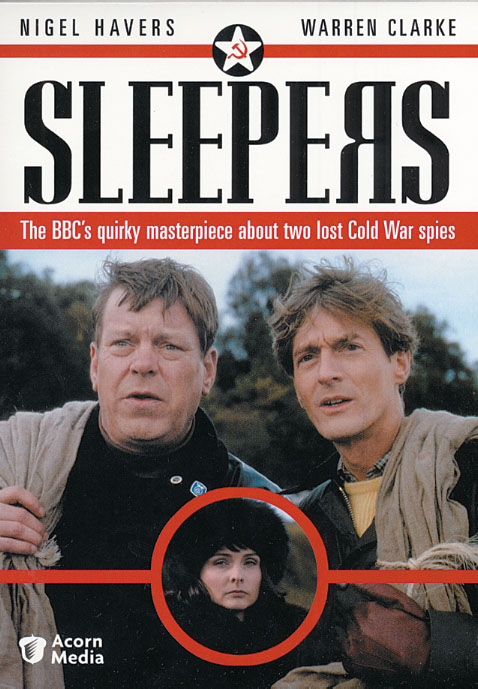

Sleepers, DVD 2-vol. boxed-set,Acorn Media, Silver Spring, Md., 211 minutes, $39.95.

AT THE HEIGHT OF THE COLD WAR in 1965, Soviet agents Sergei Rublev and Vladimir Zelenski are sent to England as a sleeper cell—and forgotten. As North Country brewery worker Albert Robinson and London financier Jeremy Coward, the two infiltrators adapt to their new life, becoming proverbially more English than the English. Twenty-five years later, the sleeping spies are aghast to find the KGB looking for them, and on the trail of the KGB are the MI5 and the CIA. Robinson and Coward are desperate not to be found, and the chase is on.

Nigel Havers and Warren Clarke star in this rollicking send-up of “Spy vs. Spy.” The four-episode series was originally aired on Masterpiece Theater and is described as “one of the best British exports of the 90s.” It may well deserve the accolade. This is more poignant human comedy than slapstick, more warm smiles than belly laughs. Its richness lies in the interplay between the working class Robinson and the wealthy man-about-town Coward, each of whom finds in his English life a personal happiness he fights hard to retain. Moscow’s a cold place even if the Cold War is long past.

This is a comedy, though, where the disordered world becomes ordered again, so all turns out right in the end. As with so many adventures, the joy lies in the journey, not the destination. This is a journey well worth taking, for the eponymous Sleepers and for those of us going along for the ride. After all, how often do we get to cheer for Russian spies?

[caption id="The39Steps_img3" align="aligncenter" width="478"]

A Visit to the Royal Opera, Covent Garden

YOU DON’T HAVE TO BE AN OPERA OR BALLET fan to have fun at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, which is home to both the Royal Opera Company and the Royal Ballet. Rich in history —it was built in 1732, suffered fires in 1808 and 1856—and now proudly flaunting a renovation that has restored it to all its glory, the Royal Opera House is a jewel that has something for everyone.

It occupies a 2 ½-acre site on the corner of Covent Garden and Bow Street. The grandly pillared main entrance is actually on Bow Street, but if you are visiting during the day, the box office entrance in Covent Garden is what you want. It’s tucked in at the end of a row of shops, and leads to a lobby whose streamlined decor belies the age of the venerable building.

You’ll soon become aware that there’s an array of desirable things to see and do. The best of them is to take a guided backstage tour. You’ll walk by mirrored classrooms where ballerinas are practicing, into design studios where designers are building intricate scale models of the staging for forthcoming productions and through workshops where seamstresses are stitching costumes and milliners are shaping hats and headdresses.

Eventually, you get behind and above the one-acre stage, where stage managers will be setting up for the night’s performance. If it’s to be an opera, the stage will be richly furnished with the sets and furniture that give Carmen the feel of gypsy life in Andalusia or make La Boheme look like it’s taking place in the low-rent district of 19th-century Paris. If an evening of ballet is in preparation, however, the vast stage will be almost bare, the backdrops doing all the work of evocation so the dancers have plenty of room to glide and twirl as skaters in Les Patineurs or metamorphose into rubies, emeralds and diamonds if Balanchine’s Jewels is being performed.

This stage is high-tech; indeed arguably the Royal Opera House is the most up-to-date theater in Europe, and with the ability to quickly change enormous and complex sets, many operas and ballets can be in repertoire at the same time.

[caption id="The39Steps_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

BRITIAINONVIEW.COM

Little, if any, of the modern wizardry is immediately evident when you step into the elegantly sumptuous auditorium. It’s a gem: a prototypical 19th-century horseshoe-shaped opera house with tiers of boxes providing excellent acoustics and seating for about 2,000 people. But here too the renovators have been at work, not only regilding the boxes and the lovely turquoise and gold ceiling, but adding such modern amenities as air conditioning.

In addition to displaying both the back and the front of the house, the tour takes you through the Amphitheatre Restaurant and onto its terrace where you can savor coffee or lunch overlooking the piazza and Covent Garden. Here it’s easy to imagine yourself back in the 18th century, when much of the surrounding area was built. Or you can picture it in the 19th century, when it was London’s main wholesale produce market, and flower girls such as Eliza Doolittle of My Fair Lady sold posies in the street. Today it still thrives as a market, though jewelry and cooking gadgets, toys and books, candles, clothes and more have replaced the vegetables and flowers of yesteryear. It’s certainly hard to envision this busy scene as the quiet garden of a medieval convent, even though its name derives from that origin.

‘In the evening, dinner is served on the elegant balconies, while a schedule of free Friday lunchtime jazz concerts attracts lots of visitors’

Another good place for lunch or a drink is the Floral Hall. The centerpiece here is a champagne bar, but more ordinary drinks and a menu of sandwiches are also available. In the evening, dinner is served on the elegant balconies, while a schedule of free Friday lunchtime jazz concerts attracts lots of visitors. Other free events include chamber music at Monday lunchtime, free televised performances that can be watched from outside the opera house in summer, and an autumn series of afternoon concerts by the Royal Opera Chorus, culminating at Christmas in a performance of A Ceremony of Carols. The monthly Tea Dances are also enormously popular, recalling, as they do, the 1920s and ’30s when elegant young couples flirted away the late afternoon in each other’s arms.

One reason why there are so many free programs is that in 1997 the Royal Opera House closed for two years for renovations. Much of the money came from public funds, including Britain’s Lottery, and it was deemed unfair that people who indirectly contributed would not be able to see a performance because of the high cost of tickets: £150 for many seats. Thus many tickets for the opera and ballet are sold affordably. These include seats called “the slips,” which are high in the theater, where the acoustics are good but sightlines are poor. Prices here range from £4 to £27. In addition, 100 of the best seats are sold at each performance for just £10. To get one of these tickets you put your name into a cyber “hat” at Travelex.royaloperahouse.org.uk three weeks ahead of time. If your name is selected, you will be notified by email. In addition, 67 tickets are held until the day of the performance, when they are sold to callers at the box office. Each person is allowed to buy just one ticket.

With such bargains to be had it is much easier to enjoy a performance at the Royal Opera House than it may first appear, and many of those who see the gold and turquoise auditorium while touring the building must find themselves longing to be there when the space is filled with the voices of the greatest singers of our age or the brightest ballerinas moving lissomely over its stage.

During the 2007-08 season, the operas being performed include both well-loved classics and modern masterworks: Iphigenie en Tauride, The Shops, Julie, L’Elisir D’Amore, La Cenerentola, The Magic Flute, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Salome, Eugene Onegin, Carmen, Punch and Judy, Tosca, Don Carlo, The Marriage of Figaro, The Rake’s Progress, La Boheme and Wagner’s Ring. Ballet lovers can delight in La Bayadère, Romeo and Juliet, Jewels, Pinochio, Les Patineurs, Tales of Beatrix Potter, Sylvia, The Rite of Spring, The Sleeping Beauty and a number of mixed programs. These performances, like the Royal Opera House itself, are among the best the world can offer. A visit is quite simply a don’t-miss experience.

Claire Hopley

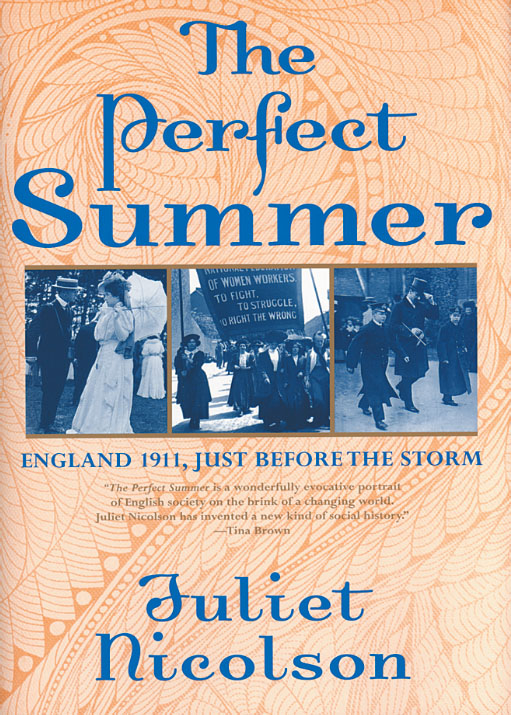

The Perfect Summer: England 1911—Just Before the Storm, by Juliet Nicolson, Grove Press, New York, 276 pages, hardcover, $25.

THE EDWARDIAN AGE WAS OVER. It was the summer of King George V’s coronation. The gilt-edged Upstairs, Downstairs world of British society basked in the sunshine of a long, hot summer. If few Brits saw the political storm clouds gathering over the skies of Europe, none could ignore the tremors shaking the established order at home.

[caption id="The39Steps_img5" align="aligncenter" width="511"]

Juliet Nicolson (granddaughter of Vita Sackville-West) has come up here with a new form of historiography, transporting the reader through the summer of 1911 in the stories of a juicily eclectic cross-section of society. We storm the streets with Ben Tillotson, leader of the dock worker’s union whose strikes paralyzed commerce in August; we dawdle away the languid hours with Lady Diana Manners through her debutant season; we attend the coronation and then devote days with George V on the upland moors eliminating wildlife; we flirt with Rupert Brooke and Virginia Stephens camping on Dartmoor; we build sandcastles at Broadstairs with the Home Secretary, a young Winston Churchill; we sneak behind the green door with butler extraordinaire Eric Horne.

The result is far from a perfect narrative, but it is great fun. What emerges is a wonderful social and political history of what was a watershed year for British society in many ways. Interweaving the accounts of two score people’s lives from early May through mid-September, the chronological narrative does not arrive at a conclusion. It ends with the summer. We are left instead with an impressionistic cyclorama of the age, rich and colorful, and a feeling of having peeked into the lives of a host of fascinating people. The Perfect Summer isn’t historical scholarship; it is an amusement park ride into the past.

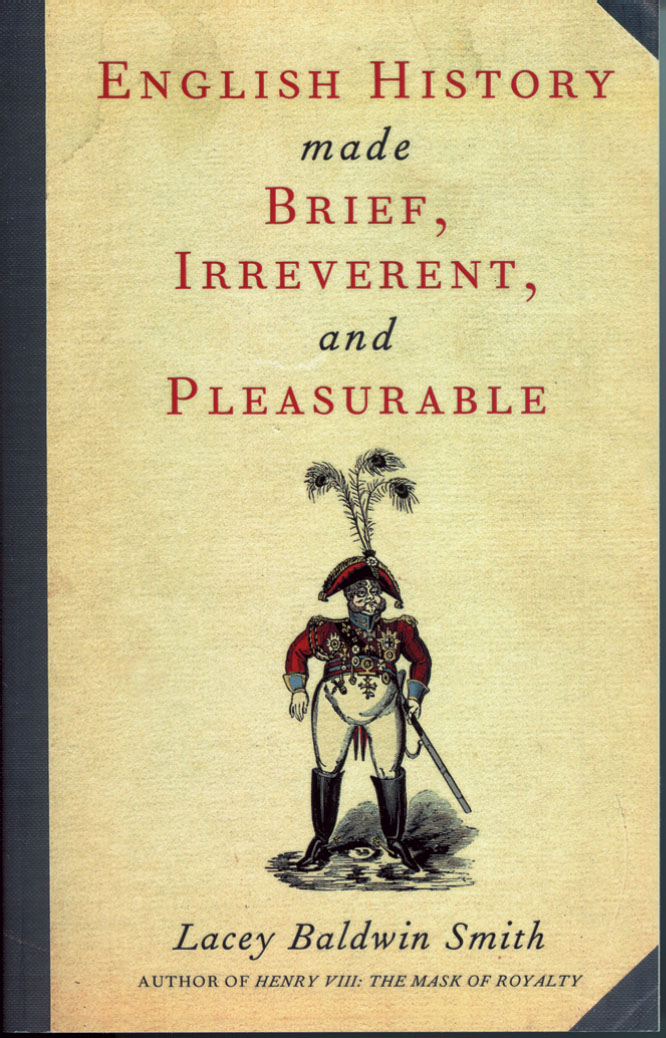

English History made Brief, Irreverent, and Pleasurable, by Lacey Baldwin Smith, Academy Chicago Publishers, Chicago, 264 pages, softcover, $17.95.

THE TITLE SAYS IT ALL. This quixotic narrative can hardly be compared to Churchill’s History of the English-Speaking Peoples, or to any of a handful of serious and competent one-volume histories of England or the island. Blessedly, it doesn’t attempt to be. But then in 264 large-print pages, there’s little room for such ambition. At that, Lacey Baldwin Smith manages to cover English history from the Celts to the Battle of Bosworth Field (1485) in 41 pages. Then, after taking us on a dizzying whirlwind ride up the present, Smith provides a 60-page chapter of thumbnail profiles of every monarch since William the Conqueror.

Whirlwind histories can be very helpful. Such treatments, however, are intinsically simplistic and carry the danger of reducing the men and women who shaped it to the broadest of caricatures.

For a light-reading overview of English history undertaken, say, before a holiday trip to our sceptered isle, the result is informative and great fun. As a serious introduction to English history, it’s not that serious (though fun, anyway). A liberal lacing of line-drawings and cartoons illustrates the book in an appropriately irreverent and pleasurable fashion.

[caption id="The39Steps_img6" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

[caption id="The39Steps_img7" align="aligncenter" width="733"]

‘Whirlwind histories can be very helpful. Such treatments, however, are intrinsically simplistic and carry the danger of reducing the men and women who shaped it to the broadest of caricatures’

[caption id="The39Steps_img8" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

[caption id="The39Steps_img9" align="aligncenter" width="666"]

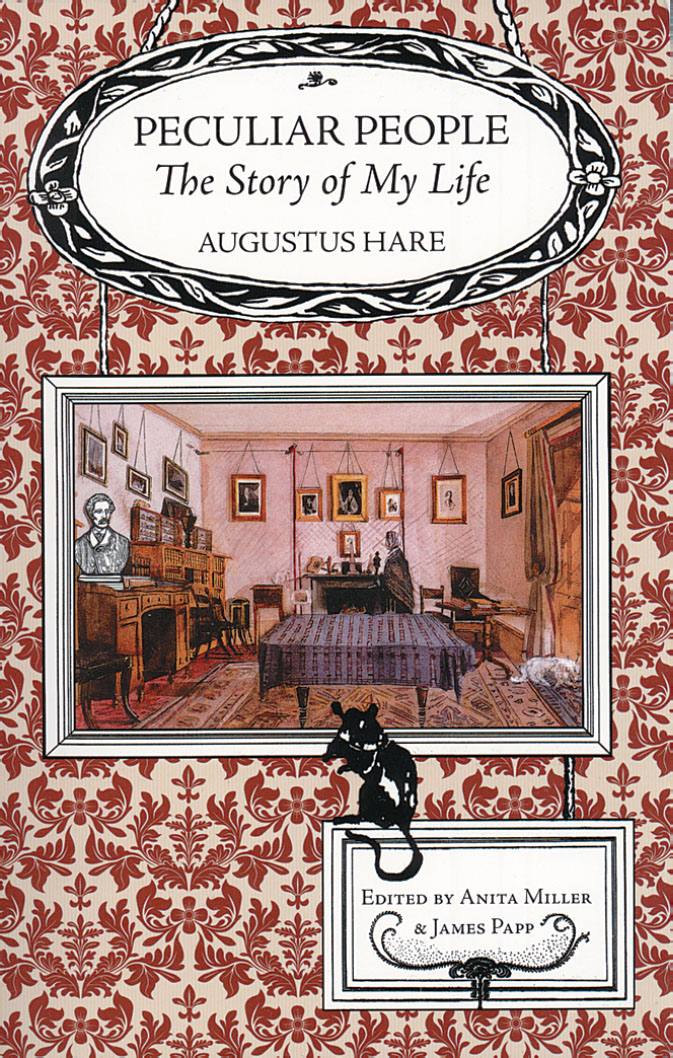

Peculiar People:The Story of My Life, by Augustus Hare, Academy Chicago Publishers, Chicago, 303 pages, softcover, $17.95.

ONLY THE VICTORIAN AGE could have produced a man and a narrative like this. Few people today have ever heard of Augustus John Cuthbert Hare (1834-1903). In his own time, however, Hare was a widely known travel writer, storyteller and memoirist. Through the latter decades of the 19th century, Hare wandered across Britain and the Continent rubbing shoulders with the odd upper classes of English society, collecting anecdotes and memories of the obscure and infamous. He wrote popular guidebooks on the English counties, Rome, Paris and Spain and kept copious journals of his adventures. Among his acquaintances were such luminaries as Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin, Robert Browning, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Mark Twain and Washington Irving.

Certainly Victorian England was pocked with characters we now call “Dickensian,” but every age and culture has its share of eccentric characters. It is Hare’s deft brush strokes of brief description that capture the personalities in the aspic of their times.

[caption id="The39Steps_img10" align="aligncenter" width="673"]

[caption id="The39Steps_img11" align="aligncenter" width="678"]

[caption id="The39Steps_img12" align="aligncenter" width="670"]

Between 1899 and his death in 1903, Hare published a six-volume autobiography (which he didn’t expect anyone save his friends, acquaintances and those mentioned to read). Unquestionably, Hare was as peculiar as those people he describes, but his memoirs offer a telling insight into his era and the eccentric folk who peopled it. In six volumes, Hare’s story would doubtless be a colossal bore. Ruthlessly edited into a single volume, however, the book is a delightful, fast-paced read that is impossible to put down.

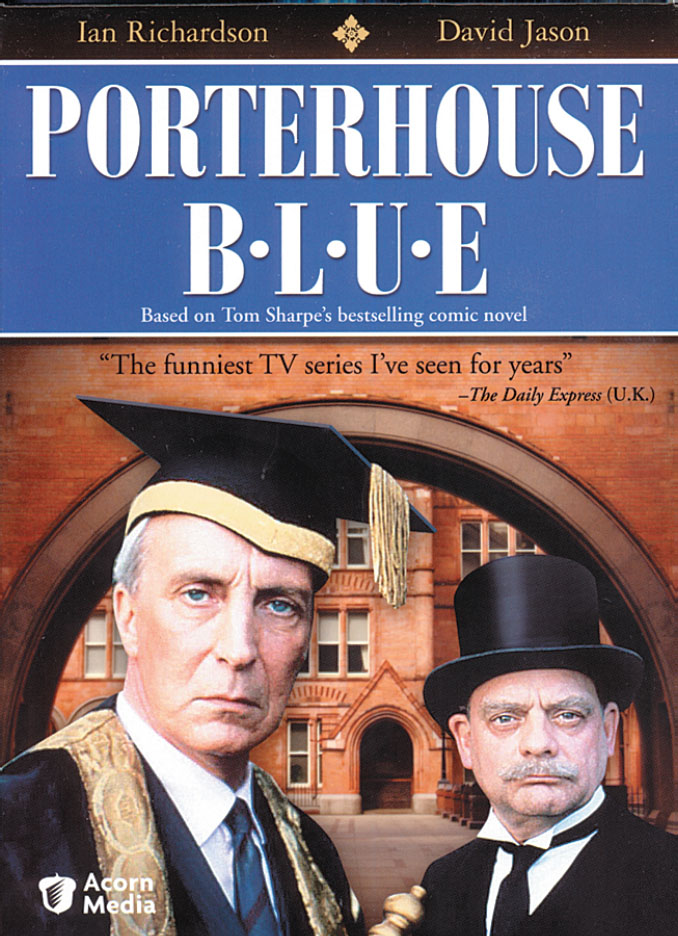

Porterhouse Blue, DVD 2-vol. boxed-set, Acorn Media, Silver Spring, Md., 200 minutes, $39.95.

PERHAPS THERE ARE NO BRITISH INSTITUTIONS as reverent of their own traditions as the colleges of Oxbridge. Enter Porterhouse College, where traditions of gentlemanly mediocrity, gastronomic excess, alcoholic haze and feudal custom go back for dusty centuries. A Porterhouse Blue is college slang for an apoplectic stroke brought on by years of overindulgence at High Table.

When new master Sir Godber Evans (Ian Richardson) enters the idyllic scene intent on radical reform (and prodded on by a Dickensian wife), the cushy and comfy, hidebound faculty and staff rise to defend the ancient ways and means of dear, old Porterhouse. ’Tis the crusty Head Porter, Skullion, who emerges as the greatest guerrilla warrior in a campaign of tricks and trumpery.

There is a fine line between satire and pastiche. Porterhouse Blue manages to wiggle along that line without disintegrating into the silly. After all, every stuffed shirt needs deflating from time to time, and in an Oxbridge College there are plenty of targets of opportunity.

Fans of David Jason from his great series, Darlin’ Buds of May and A Touch of Frost, will particularly relish his BAFTA-winning role as Skullion, both servant to all and master of all he surveys until the Porterhouse crisis emerges. Fans of P.G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster will find in this fourepisode series a shiver of delight as well. Dodgy dons and daffy aristocrats, undergraduate food fights and raging hormones: What could there possibly be to reform?

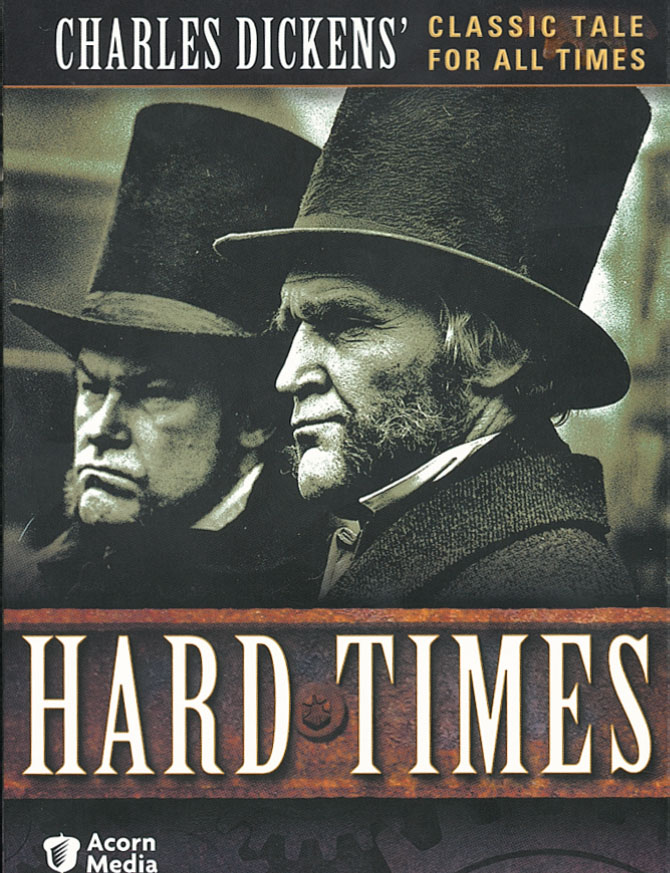

Hard Times, DVD 2-vol. boxed-set,Acorn Media, Silver Spring, Md., 203 minutes, $39.95.

IF THE DICKENS WE KNOW AND LOVE best lives in Mr. Pickwick, Tiny Tim, Pip and David Copperfield, it may be in Hard Times we find Dickens at his starkest as a caricaturist and social critic. Dickens unpacked for a genteel Victorian readership the industrial poverty and soulless mercantilism of England’s northern cities in perhaps his grimmest novel. Against a backdrop of the smokestacks and noisy, dangerous textile mills of Coketown (Manchester), Dickens tells a story of the head versus the heart.

Film or video is always at a loss to capture the deft subtleties of a writer like Charles Dickens. Nonetheless, this acclaimed four-episode adaptation of Hard Times grabs the essence: life is uncomfortable, dirty and brief for the trapped souls in the dark Satanic mills of Victorian England. Finding the nobility of the human spirit in such a state of life is a challenge indeed.

This BAFTA-winning production features Timothy West as Josiah Bounderby, Patrick Allen as Thomas Gradgrind and the suave Edward Fox as Captain Harthouse. Against such imposing and formidable men as husband, father and lover, Jacqueline Tong plays Louisa, whose force-fed worldview is challenged irrefutably by her heart.

This is not a light-and-bright-and-sparkling film. There was little color in the smog-choked streets of Coketown, or in the lives of its inhabitants. Dark interiors, dark clothes and dark views of human life were the order of the day. It is appropriately a visually somber film. The rays of light and the glimmers of the human spirit that shine through become all that much more important. You’ve got to be in the mood for something serious and reflective, but this is a well-done film, faithful to the spirit and theme of the classic novel.

Comments