AMY JOHNSON LANDED at the airfield in Darwin, Australia, on 24th May 1930 after piloting her plane 8,600 miles in 19½ days, becoming the first woman to fly solo from England to Australia. Her goal had been to beat the 1928 record set by Bert Hinkler, but she overshot it by four days. Though Amy felt like a failure, the British weren’t disappointed—the press called her the “queen of the air,” and the Daily Mail presented her with £10,000, “the largest amount ever paid for a feat of daring.” Overnight, Amy Johnson became the nation’s darling.

Born in Hull, Yorkshire, to John and Amy Johnson on 1st July 1903, Amy was the oldest of three girls. She enrolled at the University of Sheffield in 1922, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in economics, then moved to London in 1927 and worked in a solicitor’s office as a secretary. The next year Amy took up flying at the London Aeroplane Club, earning her license in July 1929. Five months later she qualified as a ground engineer, the first British woman to do so.

With a mere 75 hours of flying time, Amy determined to become the first woman to fly solo from England to Australia, and do it in record time. Lord Wakefield, of Wakefield Castor Oil, agreed to provide financial backing for the trip and shared with her father the £600 cost of the plane. The two-year-old de Havilland Moth arrived just two weeks prior to her departure, and Amy christened it jason, after her family’s fish business.

She departed London on 5th May 1930 and’ began a harrowing journey, fraught with several crash landings, monsoons, sweltering heat, sandstorms, and many delays—once she was even reported missing. Amy finally reached Darwin on 24th May, and while touring the country in the weeks following, she met British flyer Jim Mollison. They married the next year.

[caption id="TheAmyJohnsonRoomSewerbyHall_img1" align="aligncenter" width="212"]

COURTESY OF EAST RIDDING OF YORKSHIRE COUNCIL

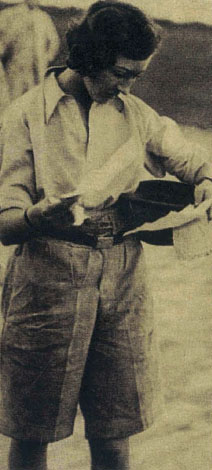

[caption id="TheAmyJohnsonRoomSewerbyHall_img2" align="aligncenter" width="142"]

COURTESY OF EAST RIDDING OF YORKSHIRE COUNCIL

[caption id="TheAmyJohnsonRoomSewerbyHall_img3" align="aligncenter" width="268"]

COURTESY OF EAST RIDDING OF YORKSHIRE COUNCIL

[caption id="TheAmyJohnsonRoomSewerbyHall_img4" align="aligncenter" width="101"]

COURTESY OF EAST RIDDING OF YORKSHIRE COUNCIL

AMY WENT ON TO MAKE many noteworthy long-distance flights from England to Europe and Asia. She became the first pilot to fly the 1,760 miles from London to Moscow in under 24 hours. In a trip from London to Cape Town, South Africa, in 1932, she beat by 11 hours the record held by her husband. Amy repeated the trip four years later, again breaking the standing record. She also endured some failures, including a 1933 flight with Mollison that landed them both in hospital with minor injuries. (In 1938 Amy and Mollison divorced, and she resumed using her maiden name.)

MUSEUM NOTES

Sewerby Hall Museum and Art Gallery, Sewerby, East Yorkshire

Telephone: 01262 673769

Admission: &puond;3.10 for adults, &puond;2.30 for seniors, and &puond;1.00 for children

Hall hours: April-September: daily 10 am-5.30 pm

Hitler invaded Poland the following year, and Amy joined the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) in 1940. For a weekly salary of £6, she delivered military aircraft from factories to air bases—routine work for Amy, who was one of the ATA’s most experienced pilots.

On 5th January 1941, Amy took off from Blackpool airport in a thick fog to transport a twin-engine Airspeed Oxford to Kidlington Airbase in Oxfordshire, a 90-minute flight. Inexplicably, she was still in the air four and a half hours later. Then she presumably ran out of fuel and had to bail out over the Thames estuary, 100 miles off course. HMS Haslemere soon arrived on the scene, but never recovered Amy’s body.

Questions surrounding Amy’s death have led to speculation that she was flying a spy mission, was shot down by friendly or enemy fire, or staged her own death. But a BBC Inside Out interview conducted in 2000 offers another explanation. Derek Roberts, a wartime clerk at the RAF flight office at the port of Sheerness, claims he typed the report submitted by Corporal Bill Hall, who was on duty aboard the Haslemere on 5th January 1941. According to the report Roberts says he prepared, the sailors threw a rope to Amy, but she couldn’t reach it. “Then,” says Roberts, “someone dashed up to the bridge and threw the engines into reverse, as a result of which she was drawn into the propeller and chopped to pieces.”

AMY’S MYSTERIOUS DEATH only added to the public’s fascination with her exploits. In 1958 Amy’s father donated her memorabilia to Sewerby Hall Museum and Art Gallery in East Yorkshire, which put the items on display in the Amy Johnson Room. The exhibit now features more than 130 artefacts, including awards, trophies, and her leather flight bag recovered from the Thames estuary. This July marks the centenary of her bi9 h, and Sewerby Hall plans to celebrate the event with lectures, musical performances, and an evening dance on July 1, with participants dressed in period clothing.

Fifty acres of parkland surround Sewerby Hall, which sits cliff-top and offers spectacular views of Bridlington Bay. Additional attractions include the mansion’s art galleries and period rooms, the formal, walled gardens, and a children’s zoo. The gardens and zoo are open year round, while the hall opens seasonally.

AVIAT RIX

Read more about Amy Johnson at BritishHeritage.com/historyonline.htm.

Comments