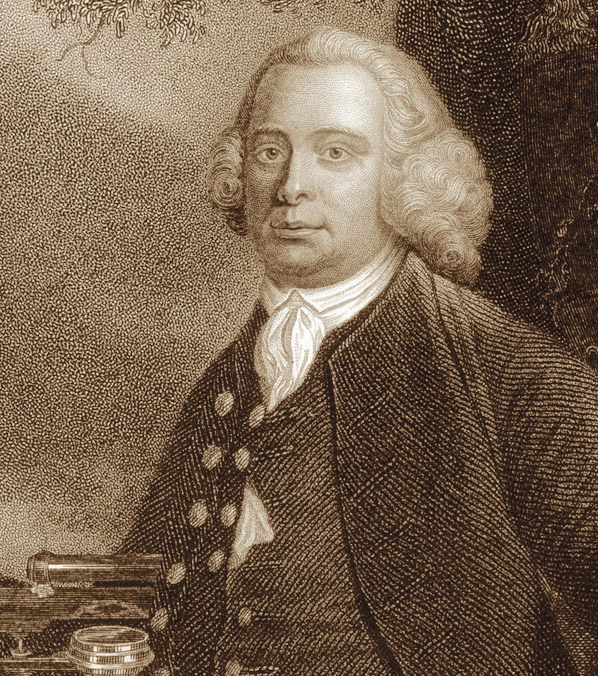

[caption id="TheBrindleyWaterMill_img1" align="aligncenter" width="781"]

COURTESY OF BRINDLEY MILL PRESERVATION TRUST

WHEN MILLWRIGHT Abraham Bennett asked his apprentice where he had gained his impressive knowledge of millwork, James Brindley replied, “It comes naturally.” The youth wasn’t bragging, just stating a simple truth.

Brindley began his apprenticeship in 1733 at Gurnett, near Macclesfield in Cheshire, where at first his fellow apprentices and Bennett derided Brindley as a “fool” and “blundering blockhead” for his tendency to try unorthodox methods that often failed.

That ability to think outside the box, however, helped make Brindley one of the leading engineers of his day, responsible for initiating Britain’s canal era, which in turn gave momentum to the Industrial Revolution.

James Brindley was born in 1716 at his parents’ small farm in the parish of Wormhill, Derbyshire. He was the eldest of James and Susanna Brindley’s seven children. When the young James was 10 years old, the family moved to Lowe Hill Farm at Leek, Staffordshire, where he showed an early interest and aptitude in mechanical things.

Brindley would often visit nearby mills and study the mechanisms used to harness wind and water to grind corn. Based on those ideas, he went on to construct model water mills to test in small millstreams that he had created for the miniatures.

At age 17 Brindley entered his apprenticeship with Bennett. Two years later, Bennett was hired to repair a Maccles-field mill that had been ravaged by fire. The mill’s superintendent, James Milner, supervised Brindley as he removed the damaged machinery. While Brindley worked, he gave his opinion on what had started the fire and how it could be prevented in the future.

Impressed with the 19-year-old’s insight, Milner requested Brindley’s help with the mill’s repair work. Bennett reluctantly gave his permission, but he closely watched the young apprentice as he rebuilt the damaged mill.

An older Brindley would remember the “delight which I felt when my work was fixed and fitted complete; and I could not understand why my master and the other workmen, instead of being pleased, seemed to be dissatisfied with the insertion of every fresh part in its proper place.”

[caption id="TheBrindleyWaterMill_img2" align="aligncenter" width="676"]

MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARY

When the mill project was completed, the men went to a local tavern, where Brindley’s efforts were derided by his coworkers. Milner quashed their ridicule by saying, “I will wager a gallon of the best ale in the house, that before the lad’s apprenticeship is out he will be a cleverer workman than any here, whether master or man.” Milner’s words proved prophetic, and Brindley’s reputation grew as a result of his work at the Macclesfield mill. When millers needed their machinery repaired, they requested “the young man Brindley,” often in preference to Bennett.

The innovative Brindley was talented, but he also grew into a man of tremendous integrity. In fact, his standards were so high that Bennett once chided him, “If thou persist in this foolish way of working, there will be very little trade left to be done when thou comes out of thy time: thou knaws firmness of wark’s th’ruin o’trade.”

Bennett found cause to be grateful for Brindley’s work ethic, however, when in 1737 the millwright undertook a commission to craft machinery for a new paper mill at the River Dane at Wild-boarclough. When he needed more information for the project, Brindley walked 25 miles to a nearby mill to inspect the machinery himself. He spent the next day—Sunday, his day off—making notes, then walked back.

On Monday morning he was at Bennett’s mill sorting out corrections to what had already been built. Bennett handed the entire project over to Brindley, who successfully finished the work by the contracted time.

In 1742 Brindley set up his own business as a millwright in Leek, Staffordshire. Ten years later he built the Leek mill and workshop, which is now the Brindley Water Mill. That same year, Brindley designed and built an engine for draining coal pits at Clifton, Lancashire, and in 1755 he constructed a machine for a silk mill at Congleton.

His reputation brought him to the attention of Francis Egerton, third Duke of Bridgewater, who needed to transport coal the 10-mile distance from his quarry at Worsley to Manchester. The duke hired Brindley in 1759 to build a canal. The result was a major technical marvel, the first British canal of the modern era.

The Bridgewater Canal opened in 1761. It was a huge financial success for the duke and a major career achievement for Brindley.

The most impressive aspect of the canal was the Barton Aqueduct, which carried the canal 39 feet in the air for 200 yards over the River Irwell. A contemporary engineer observed the aqueduct and commented, “I have often heard of castles in the air, but never before saw where one was erected.” The Barton Aqueduct drew tourists and continued to operate until 1894, when it was demolished and replaced with the Manchester Ship Canal.

Brindley extended the Bridgewater Canal to Runcorn and connected it to his next big endeavor, the Trent and Mersey Canal. Construction on that project began in 1766. Eleven years later, the waterway was open for business, complete with more than 70 locks and five tunnels.

[caption id="TheBrindleyWaterMill_img3" align="aligncenter" width="587"]

COURTESY OF BRINDLEY MILL PRESERVATION TRUST

One of the tunnels, the Harecastle Tunnel, was 2,880 yards long. The passage proved a tight fit for barges, which grew in size over the years, and men had to “leg” them along the enclosed waterway by lying on their backs on top of the vessels and pushing against the canal roof. The process was long and arduous, and consequently a second, wider tunnel was opened in 1827.

Demand for James Brindley’s expertise and ingenuity continued to grow. He was so much sought after, in fact, that his friend Josiah Wedgewood observed in 1767: “I am afraid Mr. Brindley will do much and leave us before his vast designs are over. He is so incessantly harassed on all sides, that he hath no rest for his mind or body.”

All told, the gifted engineer contributed to the building of some 360 miles of canals, including the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal, the Coventry Canal and the Oxford Canal. During its heyday, the Oxford Canal was one of the most important and profitable waterways in the nation.

In the midst of his busy schedule, Brindley took time to marry Anne Henshall in 1765. The couple had seven years together before Brindley died of complications from diabetes on September 27, 1772. He was buried in the churchyard at Newchapel.

Brindley’s mill in Leek remained in operation until it was abandoned in 1940. Eight years later a portion of the building was demolished to make way for improvements to the Macclesfield Road. The mill languished until a charitable fund was established in 1970 to purchase and restore the landmark building. Brindley’s mill was returned to working order and opened to the public in 1974; the museum portion was completed six years later.

Visitors to the museum are exposed to a multisensory experience. Guided tours meander through the restored mill’s meal floor, the stone floor and the garner floor to observe the old-fashioned way of grinding corn. The centuries-old sounds of sloshing water in the water wheel and grinding corn, combined with the smell of old timbers and freshly milled corn, waft through the building, taking visitors back in time.

The museum houses archives with detailed information about Brindley and the mill’s history. Artifacts on display include such highlights as Brindley’s level (now called a theodolite), which he used to survey his canals, and a notebook containing notes the engineer made during survey excursions.

Dr. Erasmus Darwin, grandfather to Charles Darwin and friend to James Brindley, lamented the engineer’s death in a poem that pays tribute to his skill:

So with strong arm immortal Brindley leads

His long canals and parts the velvet meads;

Winding in lucid lines, the watery mass

Minds the firm rock, or loads the deep morass;

While rising locks a thousand hills alarm,

Flings o’er a thousand streams its silver arm;

Feeds the long vales, the nodding woodland laves,

And plenty, arts and commerce freight

the waves….

A later line cites “mechanic Genius”—an apt and well-deserved honor to invoke for Brindley.

MUSEUM NOTES

The Brindley Water Mill

Mill Street

Leek, Staffordshire, ST13 8HA

Telephone: 01538 381446

Web: www.brindleymill.net

E-mail: [email protected]

Admission: Adults £2, children

and seniors £1

Hours: 2-5 p.m. on Saturdays, Sundays and Bank Holidays from Easter Saturday to the end of September. Also open 2-5 p.m. Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday from the third Monday in July through August

Comments