[caption id="TheContinuingSearchforBritain_img1" align="aligncenter" width="261"]

BRITAINONVIEW

UNTIL RECENTLY, BEING BRITISH never needed defining. It was just there. After all, being British was something that evolved over the centuries, unlike in the States where our national identity was purpose-built. Great Britain’s defining institutions and traditions, from a cup of tea to the Church of England, a pint in the pub and the Royal Family, Guy Fawkes Night and a flutter on the Derby, simply existed as part of the fabric of everyone’s lives. To be sure, all these things were hard fought and hard won over the centuries. But they created a sense of common identity, and provided a sense of belonging that didn’t have to be thought about much.

Last issue, we toddled around Britain to visit in situ some of my personal favorite representative sites, themes and events that might be commemorated in a proposed new National Museum of British History—in search of that now smoky identity.

We left our chronological meander through the past with the tumultuous Tudors and all the upheaval that surrounded the English Reformation. That tumult still shook society through the 17th century when the clumsy Stuart kings took the throne. It shook the country into Civil War. The Commandery in Worcester that Sian Ellis writes about in this issue is the only museum in England devoted to the Civil War. My favorite visit detailing life through those times, however, is Llanchaiach Fawr near Nelson in South Wales. The living history museum brings the manor to life in the 1640s when King Charles came to visit.

‘Then came Victoria. The kingdom by the sea became an empire and the machine began to take over the world’

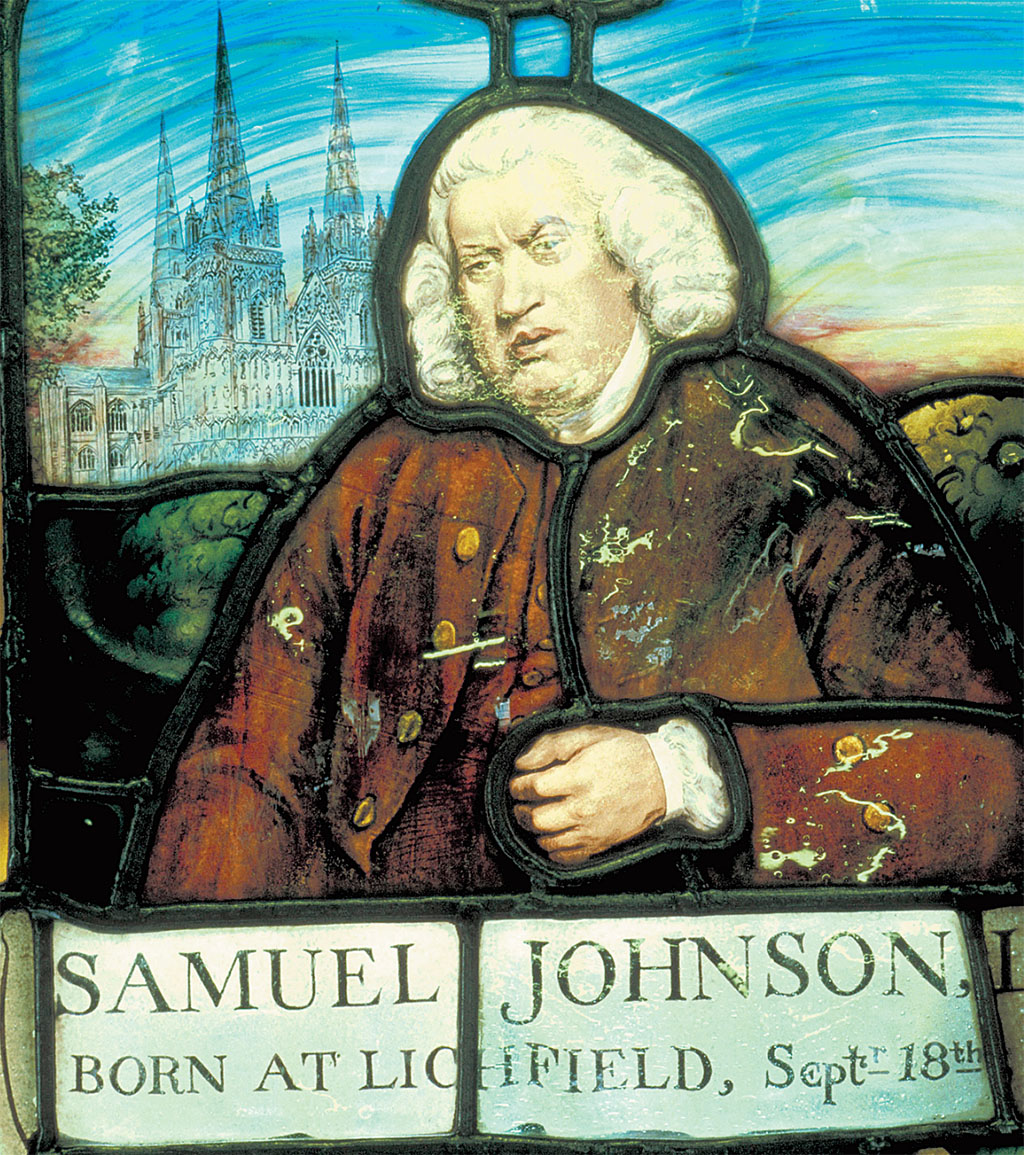

Georgian England saw a country on the move and the rise of London as the great metropolis it is today. No one embodies 18th-century London like the good Dr. Samuel Johnson. After all, it was the great Augustan Age of literature as well. Even those who aren’t of a literary bent ought to take a visit to Johnson’s House tucked off of Fleet Street in Gough Square.

The 18th century, too, was the time of Britain’s rise as a dominant sea power. At Chatham Dockyard, Britain’s ships-of-the-line were built for 200 years. The complex tells the story of Britain’s mighty warships, as does the Naval Museum in Portsmouth. By the end of the 1700s, Bath was all the rage, and retains its profusion of magnificent Palladian architecture.

The end of the Georges was in sight by the Regency of him who became the negligible George IV. The mighty symbol of his opulence and sense of himself is the Royal Pavilion in Brighton. It’s a magic carpet-ride of a visit—though few people know what to make of the Aladdinate pile. Part of the Regency’s legacy, however, is the great British tradition of the recreational seaside, and Brighton Pier still bubbles in the prime of life.

And then came Victoria. The kingdom by the sea became an empire, and the machine began to take over the world. Terrific Victorian visits abound. Portsmouth’s HMS Warrior, the mighty innovative 1860 battleship, patrolled the world to maintain the Pax Britannica. From Porstmouth, it’s a quick ferry ride over the Solent to the Isle of Wight for a visit to Osborne House. It was Queen Victoria’s real home, built for her by her beloved Prince Albert, and it shows everywhere.

Among the many places where you can see how machines defined life, perhaps the most memorable is the textile village at Quarry Bank Mill in Styal. And possibly no machine changed 19th-century life quite like the railroad. The National Railway Museum in York makes the story come alive. York’s Victorian train station itself, with its magnificent decorative wrought iron, was the largest in the world when it was built in 1877.

The brief but glamorous Edwardian years of the early 20th century ended abruptly with the not so Great War. Those were the years when fashionable long house parties bloomed in country manors and mansions all across the landscape. If you need an excuse to visit much-touristed Warwick Castle, this is a good one. Edward himself was the guest at a weekend party in the private apartments in 1898.

Two world wars became Britain’s defining points in the last century.

[caption id="TheContinuingSearchforBritain_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

BRITAINONVIEW

Churchill’s country home in Kent, Chartwell, captures the man who captured the era. There is also the moving American Military Cemetery in Madingley, on the outskirts of Cambridge. And many times, I have returned to the RAF Memorial at Runnymede, which overlooks the Magna Carta meadow and the Thames near Windsor.

[caption id="TheContinuingSearchforBritain_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

BRITAINONVIEW

With every name chiseled into the marble alcoves of the colonnade, the memorial remembers the 27,000 British and Commonwealth fliers who died in World War II with no known grave. It is a moving place.

As the 21st century unfolds before us, Britain is engaged in its most serious identity crisis since the Act of Union brought the kingdoms together. Devolution has been the watchword of the day as the Scottish Parliament and the Welsh Assembly have taken varying degrees of self-determination and self-government unto themselves. The Scottish National Party and Plaid Cymru have continued to be a rallying point for nationalists who seek independence from the dominant English majority and from the governing parliament of Westminster.

Meanwhile, the increasing ethnic diversity of Britain’s large cities has created enclaves of citizens and new arrivals to the kingdom by the sea who do not identify with Britain’s past and have no allegiance to traditional and hard-won British values. Such cultural icons as Shakespeare and Blackadder, Tennyson and Monty Python mean little to those whose roots lie in Pakistan, Bulgaria and the West Indies.

With folks less and less sure of their British identity and what constitutes “being British,” it is hardly surprising that they have increasingly identified themselves more locally—with what they know and understand. The idea of a Museum of British History is seen as but one anodyne, helping people understand the integrated and brilliant heritage of the nation.

BUT WHAT DO YOU SAY? Thomas and Diane LeBaron of Conway, N.H., rather agree with my despair of capturing it all in one place: “No museum with everything meaningful gathered in one spot can replace the unequaled pleasure of traveling about as we have done, of suddenly coming upon an impressive sight, of seeing a carved White Horse from the train window, of touching the Roman walls of the baths, of mingling with the lovely people—or of having a pub lunch with a pint!”

From Titusville, Fla., Tad Berkowitz offers some practical advice: “I am both a visual and audio learner. My favorite flavors are living history formats. A moving, hearing series of experiences would delight me more than looking at nonmoving artifacts, except as used as example in a context of the thinking, dress and language of the times.”

When we North America Anglophiles and expatriates of the centuries return to Britannia, we are often too eager to see the sceptered isle as a place ideal and idyllic. She happily obliges. Of course, we do not put Birmingham, Bradford, the Rhondda and the council estates of New-castle on our itineraries. Understandably enough, we go to Bath and York, the Cotswolds and the Trossachs.

The National Museum of British History, though, is not for us overseas visitors (though I’m sure we’ll be made very welcome). This is for the Brits—Welsh, Scottish and English—who did carve a common identity for themselves, who gave us the Industrial Revolution, representative government, the Boy Scouts, the hymns of Charles Wesley and, yes, a proper cup of tea.

No question, putting together such a museum will be quite a challenge.

ELSEWHERE ON THE STAGE of Britain’s culture wars, Parliament turned down the idea of a referendum on the European Union’s Lisbon Treaty, despite polls showing that some 90 percent of the British people wanted such a referendum. Each of the three political parties ran the last general election on a platform promising the people a vote on the new EU constitution. When the formal proposed European constitution was turned down elsewhere, Brussels gussied the document up a bit and reintroduced it as a “treaty” instead of a constitution. Virtually every party acknowledges that it’s the same thing.

The British voters are feeling more than a little upset and betrayed. PM Gordon Brown was well aware that if the matter went to the voters, the manifesto would be defeated overwhelmingly. According to a Daily Mail poll, 80 percent would vote against it. Now, the oddsmakers and pundits are near unanimous agreement that the same thing will happen to Brown in the next general election.

‘Parliament rejected a referendum on the Lisbon Treaty despite polls showing that 90 percent of the people wanted one’

Meanwhile, Britain’s search for its national identity goes on. A government report titled “Citizenship: Our Common Bond,” commissioned by the PM and authored by former Attorney General Lord Goldsmith, makes a variety of suggestions that are not getting a warm reception and are likely going nowhere. Among the recommendations are formal citizenship ceremonies and an oath of allegiance for schoolchildren, a reform to the national anthem, flying the Union Jack outside of everyone’s house, council tax rebates for good citizens and a Deliberation Day in advance of general elections to encourage people to engage in political debate. No, I’m not making this up.

As here in the States, the British are seeing an end to a 10-year run-up in housing prices and for some of the same reasons—no down payment and interest-only mortgages. Many people are finding themselves vulnerable to negative equity and rising interest rates. To compensate, Chancellor Alistair Darling revealed a new budget this spring raising the tax on beer, liquor, tobacco and petrol. Sounds like a perfect way to keep the taxpayers’ spirits up. And think we’ve got it bad in the States? Petrol prices are now approaching $10 a gallon across the UK. Taking the train looks better and better.

Despite the exchange rate, Americans are planning to travel to Britain this year in numbers at least equaling last. And that is good news, not only for the British economy, but also for us. After all, it is much easier just to vacation at the beach. It is hardly news to British Heritage readers, though, that travel across Great Britain is a delightful, invigorating and intrinsically educational investment of time and resources.

Ironically enough, we overseas Anglophiles have a very clear sense of British identity. We have a great deal of fun toddling around the back streets of London, the country lanes of the Borders and West Country villages in search of it. But we know that for which we’re looking.

[caption id="TheContinuingSearchforBritain_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

BRITAINONVIEW

Comments