The narrow coal valleys of South Wales fan out like spider veins above the harbor cities of Cardiff and Newport. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, workers poured into the valleys to mine the narrow seams of steam coal that fueled the empire’s industrial and naval might.

[caption id="TheLifeandDeathofKingCoalinSouthWales_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="834"]

GETTY IMAGES

Industry & Empire Fourth in a Series

ANTHONY ERNEST, a town councilor for Penarth in South Wales and proprietor of Brecon Lodge, was explaining the local coal industry. “It was all one big machine, you see. Everything was a part of it—every business, every building, in every town. Penarth was as much a coal town as Pontypridd.” This was quite a claim. Penarth was—and is—a charming Victorian seaside town, full of parks and sunlight, and bearing no resemblance to the endless terrace rows and industrial landscapes in the coal towns 30 miles to the north.

‘Everything was a part of it—every business, every building, in every town.’

This claim leads to a remarkable story—of a single, giant machine that for 100 years ripped coal from under the mountains that ringed South Wales and poured it onto ships at its coast. The machine occupied all the land of South Wales, encompassed all the businesses and employed all the people. Those who were part of this machine had a name for it; they called it “King Coal.”

For centuries, the region was a lightly populated rural backwater. The coast held a choice of natural harbors, each with a small fleet of fishing boats. From there, rivers led steeply uphill into deeply cut valleys, topping off at a huge crescent of mountains, cliffs and moors. If you looked at the cliffs and the exposed rocks on the high valley sides, you could see exposed seams of iron ore, coal and limestone. Downhill, water cascaded violently through a narrow valley. By 1780 this was about all you needed to make money. Ironworks took the ore, then used coal and limestone to refine it into pigs of iron, bellowed and stamped using the water power in the valley below.

Industrialization had begun. Heavy ores, coals and rocks were rolled downhill on wagons with grooved wheels that ran on rails, known locally as “rail roads.” By 1800 a series of canals and rail roads linked the mountain ironworks with the booming port of Cardiff (a minor market town only a few years earlier). In

1804 Richard Trevithik took a new type of steam engine he had invented, mounted it on the grooved wheels and used it to drag a train of five wagons—history’s first locomotive railroad.

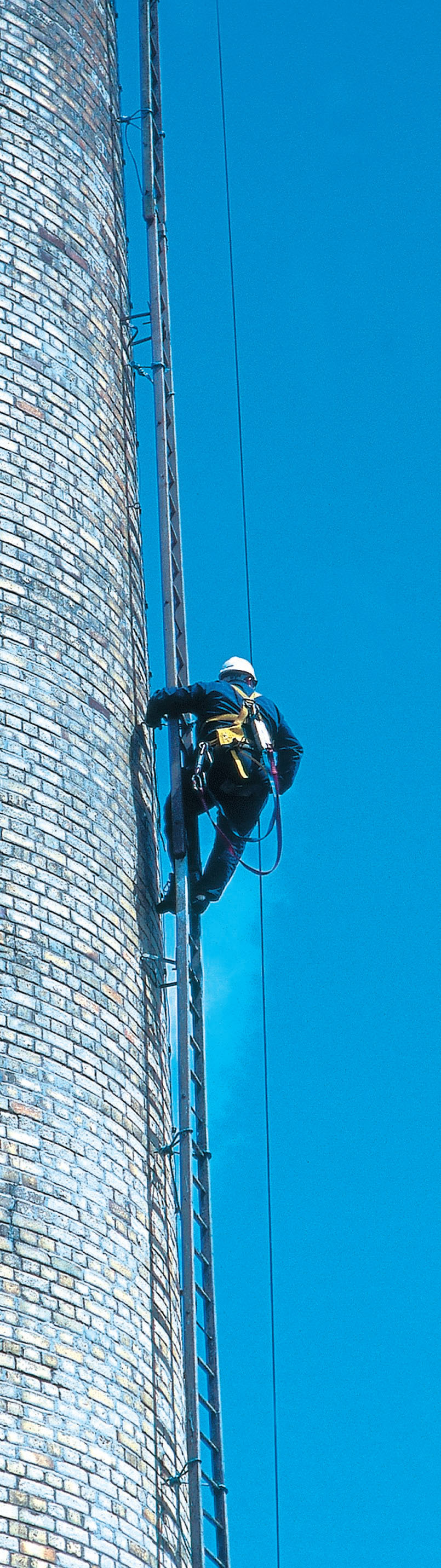

[caption id="TheLifeandDeathofKingCoalinSouthWales_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1021"]

Jim Hargan

Initially, Welsh coal was merely a part of the Welsh iron industry, but it didn’t remain that way. The coal measures near the iron mines had seams of bituminous coal, well suited for making the coke required by iron furnaces. Some distance farther down, geologically older strata contained harder coal, with a greater energy value per ton and fewer of the chemicals that caused so much smoke. Not that anyone cared about pollution, but the Royal Navy cared very much about not having thick smoke plumes that revealed its positions, as well as having to carry less coal for the same amount of energy. That South Wales was close to the great naval yards was a bonus. By the 1860s, the Royal Navy used only “steam coal” from South Wales to fuel its engines. In vain did other collieries protest that their product was nearly as good, and a lot cheaper. Welsh steam coal had become the quality standard for the world. King Coal was born.

To start a mine in South Wales, a mine owner would buy the mineral rights to a property, frequently on a short-term lease of 20 years or so. He sank two shafts—the first one to find the coal, the second to work it. Once the mine was in operation, fresh air, men, and materials were sent down one shaft, while coal and stale air was drawn up the other. Doors were placed in the mine to force the air through all the tunnels, and little boys would be stationed in the dark to open the doors when needed, and paid a halfpenny for a 12-hour shift.

TO MAKE THE MINE profitable, the mine owner needed to find several seams of coal at different depths. Welsh coal seams were irregular and unpredictable, broken by faults and distorted by folding. They were also narrow. A typical seam was only 1 yard high, and few reached more than 5 feet. Good steam coal would be worked in seams as narrow as 2 feet, with miners lying down to swing their picks.

For five months of the year, none of the miners saw daylight, as the shift changes would occur before the late winter sunrise and after the early winter sunset. Thankfully (from the mine owners’ point of view), men were cheap and easily replaced when injured or killed. In the late 19th-century South Wales pits, a man was injured every two minutes, and killed every six hours.

The South Wales district was nearly unpopulated before the advent of King Coal, and all the miners had to come from elsewhere. Some came from Wales, but many were from England, Scotland, Ireland and the Continent. There was a fair flow of Italian families, who, quite sensibly stayed above ground and opened cafes (known as “Breccis”) for the workers, where traditional Italian and coarse British fare mixed with good talk and good coffee. The Welsh claim that during the last part of the 19th century, South Wales was second only to the United States for immigration.

The workers and their families lived within walking distance of the mines—smack dab in the back end of nowhere. They resided in company-built housing, usually stone row houses, the typical design of industrial housing in Great Britain. Each was one of a long row of small, attached two-story houses, and consisted of two rooms downstairs and one or two upstairs. Behind or in front of each unit would stretch a skinny slice of land, for vegetable farming and waste disposal. In the steep-sided coal valleys, these rows of houses stretched in long terraces, down the mountainside from the mine shaft. The housing rent was deducted from the workers’ pay, and the rest of their pay was received in tokens that could be spent only at the company store.

With coal grates, kitchens and flagstone floors, these were not bad houses by the standards of the time. Even today they are perfectly nice for a classic family of four (when you add plumbing), and remain in use throughout Britain. Miners, however, did not live in families of four, but rather in large extended families; some would even take in boarders. The tiny cottages were incredibly crowded, especially when the men came home from the mines—fathers and sons (and even grandsons) together, with coal dust ground into every pore of their skin. All would expect a hot bath in a tub in front of the grate, oldest first, the water heated and poured by the womenfolk. Next shift, men, clothes and cottage would all be spotlessly clean. Women aged quickly and died young.

Welsh steam coal was pouring into the holds of ships aimed toward every corner of the world.

[caption id="TheLifeandDeathofKingCoalinSouthWales_img2" align="aligncenter" width="805"]

Jim Hargan

This, then, is how the machine called King Coal controlled mountainous South Wales. From there, King Coal stretched downhill toward the coast in a fine web of railroads, typically two to four tracks wide, often with competing lines paralleling each other. Towns at rail intersections gained markets, serving the needs of the mining folk isolated up in the valleys. Here the coal cars would be aggregated and sent down to the seaports, the railroads continuing to hug the riversides.

Various seaports were used, depending on which valley the coal came from. Many of the coal valleys flowed together and fed the giant ports of Newport and Cardiff. Some valleys fed into minor rivers, and these flowed toward smaller ports such as Penarth and Barry. Cardiff was by far and away the most important of these ports, and contained the Coal Exchange, a hugely grandiose Victorian pile where money flowed into King Coal from around the world. The smaller ports, however, give a clearer picture of King Coal at its port end.

Penarth, straddling a headland at the outflow of the Ely River, was established as a port when early entrepreneurs impounded the Ely’s mouth behind tidal locks. Ships would enter the locks at high tide, then remain afloat and receive their coal while the tide fell, typically 40 feet. As this was a labor-intensive business, a large number of workers had to be housed close by, crowded into the familiar terraced row houses along the docks. Coal loading was a dusty business. Having the texture of talcum powder, the dust would billow up with every hopper dumped into a hold. It remained suspended in the air, and settled in the houses and kitchens and lungs of all the dockworkers.

Uphill, above the dust, resided the supervisors and white-collar workers who kept the docks humming. They too lived in row houses, but somewhat larger and with a little architectural flair to show their status. Up another block and facing the sunny south was the neighborhood of the top managers and sea captains. Again the houses formed a row, but this time large and substantially built, with careful architectural details and servants quarters behind Dutch dormers.

At the top of the hill stood the houses of the ship owners and mine owners—detached mansions in the grand style. Here survive the parks they built for themselves, still superbly landscaped, leading down to the town’s small shingle beach. Along this beach stretched the Esplanade, with a wonderful Victorian dock. Once a year, the mineworkers had a weeklong holiday, and would spend their hard-saved money at the sea resorts owned by the Coal Machine—supervisors at classy Penarth, laborers at nearby Barry.

In the mid-19th century, global economic forces caught up with the iron mines. Foreign iron ore seams—flatter, thicker, fault-free—could be mined and their ore transported to South Wales cheaper than men could mine South Wales ore. The iron mines died, replaced by giant iron and steel works that used Welsh coal to refine imported ore. It was a portent of the future, as the Welsh coal seams were just as thin, contorted and faulted as the iron seams. No one noticed, however, as there was never enough Welsh steam coal to fuel the steam engines of the world.

[caption id="TheLifeandDeathofKingCoalinSouthWales_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

Coal was now the only industry in the region, and King Coal was in control. In other regions, competition was driving technological advance, increasing productivity per worker, making workers fewer and more valuable, and lowering the cost of transportation. None of this happened in South Wales. By that time, a handful of men controlled enough of the mines, railroads and ports to make collaboration more appealing than competition. In South Wales, capitalist competition had stopped, and an increasingly tiny capitalist class had become one big happy family.

This was not lost on the workers. At the end of the 19th century, the miners saw this as the first stage of the decline of capitalism as predicted by Karl Marx, and the first step toward the Workers’ Revolution. To the increasingly radicalized coal workers, narrowly focused demands would only stretch out their misery; they aimed for nothing less than the start of the revolution and the end of capitalism in Great Britain. Intransigent, no-compromise management positions led to one disastrous strike after another, each one pushing the miners into deeper poverty and making the mine owners’ combine even stronger. But this wasn’t what killed King Coal; at most, it just shaved a few decades from its life.

King Coal reached its apogee in the decades between 1880 and 1914. In that period, Welsh steam coal was pouring into the holds of ships aimed toward every corner of the world, as well as fueling all the ships of the Royal Navy. In addition, big iron and steel companies founded giant factories to use Welsh bituminous coal with their imported ore, and Welsh “household coal”—the lowest grade—flowed to home furnaces throughout Britain. The mine owners could sell everything they dug up, at a huge profit. They did not need to modernize; they just threw more men down the holes, and more coal came up.

[caption id="TheLifeandDeathofKingCoalinSouthWales_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

South Wales was producing an out-of-date product at an inflated price, using antiquated methods in run-down pits.

This all ended in August 1914. Once more, no one noticed it happening. All international exports ceased, but wartime orders took up the slack, with the Royal Navy ordering 10 times more steam coal and the steel works running 24/7. Everyone assumed that Welsh coal exports would pick up again after the Armistice, but they didn’t.

During the war, the industrial world had discovered the many weaknesses of the old reciprocating steam engines that ran on special Welsh coal, and had replaced them with petroleum-based engines or electricity. It’s true that, then as now, most electricity is derived from burning coal to produce steam, but the new steam turbine generators could burn any grade of coal, and operators did not need to pay a big premium for Welsh coal.

South Wales was in fact producing an out-of-date product at an inflated price, using antiquated methods in rundown pits. Workers and owners continued striking and exploiting as before, but pits closed every year from 1918 on. World coal demand remained high and climbing (it would triple between 1914 and 2004), but Welsh coal now cost too much.

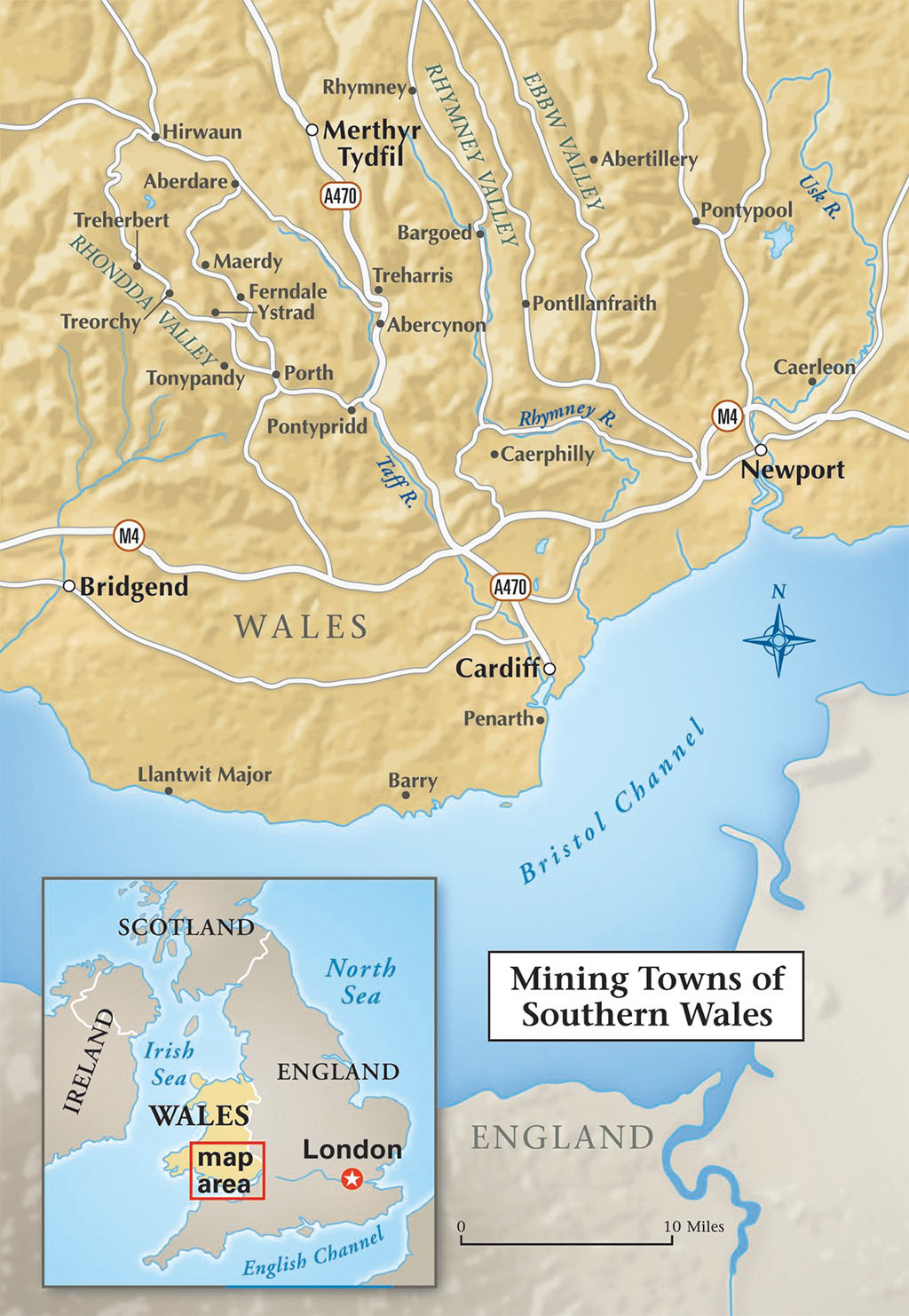

[caption id="TheLifeandDeathofKingCoalinSouthWales_img5" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

BLUE MARBLE MAPS, LLC

In 1947 politicians stepped in to save the day. The postwar socialist government nationalized the core components of the British economy, including coal mining. The new National Coal Board poured money into modernizing the South Wales pits, bringing in new technology, improving worker productivity and making the mines safer work environments. It didn’t do any good. By 1970 you just couldn’t make any money by digging steam coal from seams that were a half-mile underground and only 20 inches thick—and which might, at any point, be broken by a fault line that had sent the remaining seam goodness-knows-where.

It didn’t help that the government turned out to be lousy at managing a specialized business, putting expensive technology down pits and then closing them soon after.

Nationalization ended in 1985, amid the heavy politics and enormous rancor that accompanies the end of any government program that takes money from one group of taxpayers and gives it to another. The government sold the mines it could, and closed the mines it couldn’t. By 1992 only two deep-shaft mines remained in South Wales. Old King Coal was dead.

Comments