REFLECTIONS WITH GEORGE, LORD CAREY, ON HIS TIMES AND OFFICE.

[caption id="TheLordArchbishopofCanterbury_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

[caption id="TheLordArchbishopofCanterbury_img1" align="aligncenter" width="847"]

“Many Britons have abandoned regular religious worship, but they still hanker after the spiritual lead an Archbishop of Canterbury provides,” said former British Foreign Secretary and novelist Douglas Hurd in 2002. Whether this is true or not, the rich tradition that dates back to the 6th century makes the position of Archbishop of Canterbury one of the most notable throughout the world. It is an office that ranks just below the sovereign, who is still considered the head of the Church of England.

Pope Gregory the Great (590-604), regarded as the founder of the archbishopric at Canterbury, was convinced that the day of judgment was close at hand, and that, as pope, he had an obligation to preach the Gospel to all parts of the world. He therefore sent Augustine, a missionary monk, to England to try to bring the English people into the Roman church. Upon reaching England, Augustine approached King Ethelbert in Canterbury, which was then the capital of the kingdom of Kent. Pope Gregory’s plan was to have London established as the primary see. Augustine was unable to proceed to London, but his visit proved so successful in Canterbury that it ensured Kent’s capital would duly become England’s ecclesiastical center, and in AD 597 Augustine became the first Archbishop of Canterbury.

Another part of Pope Gregory’s original plan was that two ecclesiastical provinces would be established in England under the primary see, with one in Canterbury in the south of the country and the other in York in the north. This concept resulted in a longstanding struggle over the respective ranks of the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Archbishop of York, and which took precedence in the church hierarchy. The matter was firmly and finally resolved by Pope Innocent VI in the 14th century, when he decided that the Archbishop of Canterbury would be recognized as Primate of All England while the Archbishop of York would be titled Primate of England. The preeminence of the Archbishop of Canterbury was further acknowledged by an act of Parliament during the reign of Henry VIII.

[caption id="TheLordArchbishopofCanterbury_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Dana Huntley

GEORGE CAREY MAKES THE HISTORY OF THAT OFFICE COME ALIVE.

George Carey, the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1991 to 2002, makes the history of that office come alive as he reflects on his own years in the position. In his beautiful, rich and soothing voice, so familiar to anyone who has ever heard him preach, he offers personal thoughts on those who came before him:

When I was Archbishop of Canterbury—the 103rd actually—there were times when, as I looked around the ancient chapel at Lambeth Palace, I marvelled at being part of a rich history of the Church in England. Among my predecessors were the first archbishop—a timid monk, Augustine, who was sent by Pope Gregory the Great to restart the church in England in 597 AD. Then there was Thomas Becket, probably the most famous Archbishop of Canterbury. For my money, Thomas Becket was not a great archbishop. He spent most of his time quarrelling with the king and was never long enough in the country to be an effective archbishop. It was his martyrdom that made him famous. In my opinion another Thomas was by far a better archbishop. This was Thomas Cranmer, who gave us the incomparable prayer book, or Book of Common Prayer, whose impact on the English language was so amazing. He too was a martyr, but a far more effective archbishop.

In addition to Thomas Cranmer, Carey feels an enormous debt is also owed to William Tyndale, who translated the Bible into English, and to William Shakespeare for literature and language.

The very earliest holders of the see of Canterbury were appointed by the pope and traveled to Rome to receive confirmation of that appointment in person. In the 16th century, Henry VIII set himself up as head of the Church of England when he split with the pope by divorcing Catherine of Aragon, his first wife, so that he could marry Anne Boleyn. Dating from this break with Rome in 1558 and into the 1800s, Archbishops of Canterbury were selected by the British monarch. Beginning in the 19th century, it fell to the prime minister to select the archbishop in the name of the monarch by presenting a name to the king or queen for confirmation. There have been a number of times when the office was left vacant for a long period upon the death of the Archbishop of Canterbury; in the mid-1600s the position was vacant for 15 years.

Since 1977 the power of the appointment has been in the hands of the Crown Appointments Commission, which is usually made up of members from the House of Clergy and the House of Laity within the Church of England. The Crown Appointments Commission shortlists candidates and forwards two names to the prime minister, who, in turn, commends one name to the reigning monarch for approval.

When Carey was invited by then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to be Archbishop of Canterbury, he and his wife Eileen were as surprised as anyone. He had only been Bishop of Bath and Wells for three years; he was not one of the 26 bishop members of the House of Lords because he was too junior for such a position; and almost all his predecessors had been graduates of Oxford or Cambridge, while he had never been to either. Carey was probably the first choice of the Crown Appointments Commission because, among other reasons, it wanted a younger person who could give at least 10 full years to the job, and it desired someone with a passion to put mission at the very top of his agenda.

[caption id="TheLordArchbishopofCanterbury_img3" align="aligncenter" width="799"]

The Granger Collection, New York

ARCHBISHOPS HAVE TAKEN A LEADING ROLE IN THE EVENTS OF THE THEIR TIMES

After serving for almost 12 years, Carey retired at the end of October 2002 and accepted a life peerage; he is now known as Lord Carey of Clifton. He is one of seven of the 20th-century archbishops who have chosen to step down after serving for a number of years. When he submitted his request to retire to the queen, Carey said: “I feel certain that it is the right time to retire after serving eleven-and-one-half years in a demanding yet wonderfully absorbing post. I look forward to exciting opportunities and challenges in the coming months, and then to fresh ones in the years that follow.”

Carey’s life continues to be full as he and his wife of more than 45 years stay close to their children and 13 grandchildren. He also continues to do lots of interfaith work, gives many lectures each year and, as of November 2005, is a fellow at the Library of Congress. As such, he spends considerable periods of time in the United States, most of it in Washington, D.C., where he is working with an interfaith church.

Carey was born on November 13, 1935, in Bow, in the East End of London, the son of a hospital porter and his wife. Surprisingly, he is the first archbishop to write an autobiography. The 2004 book, Know the Truth: A Memoir, gives an interesting and entertaining account of the position by someone who knows it personally, though he tended to be gentle in writing it and to see good in everyone he mentioned.

When asked about some of his favorite moments from his time as archbishop, Carey said that he had many, but one that readily came to mind was the very special relationship he had with the monarchy, “as sort of vicar to the royal family.” He elaborated on some personal anecdotes that reflect upon this relationship. He was a particularly devoted fan of Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, and related this story, also in his autobiography: “At state banquets it was often my privilege to escort the Queen Mother—indeed, it became such a habit that on one occasion, as the royal line was forming, Prince Philip hurried up his mother-in-law with the words, ‘Come on Mother, your taxi is waiting!’ She would beam with delight, and holding firmly on to my arm we would enter behind the queen to the strains of the national anthem.”

Carey recalled Prince Philip’s dry sense of humor and wit, both in the above incident and when the archbishop recently gave a speech in the presence of the queen and Prince Philip on the subject of reconciliation. At the end of the address, Prince Philip approached Carey and said, “You know, you used the word reconciliation 57 times,” to indicate that he had been counting while listening.

The retired Archbishop of Canterbury also has a number of regrets from his years in office. He feels he could have spent more time with Prince Charles and Diana, Princess of Wales, to try to save their marriage, although he admits that much of the damage had already been done by the time he became archbishop in 1991. Another regret is that, while he supported the outcome of the vote that would prohibit the ordination of bishops who were practicing gay clergy, he feels he might have done much more to ease feelings and tensions on both sides.

Times shape the office of Archbishop of Canterbury, and during times of crisis at home the archbishop needs to stay close by to offer a comforting and calming presence. Thus, in these perilous times within England, with terrorist bombs going off in London in July 2005, the current Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr. Rowan Williams, may not be able to travel the world as much as Carey could. Whether Archbishop Williams will travel in years to come, depends on conditions no one can foresee.

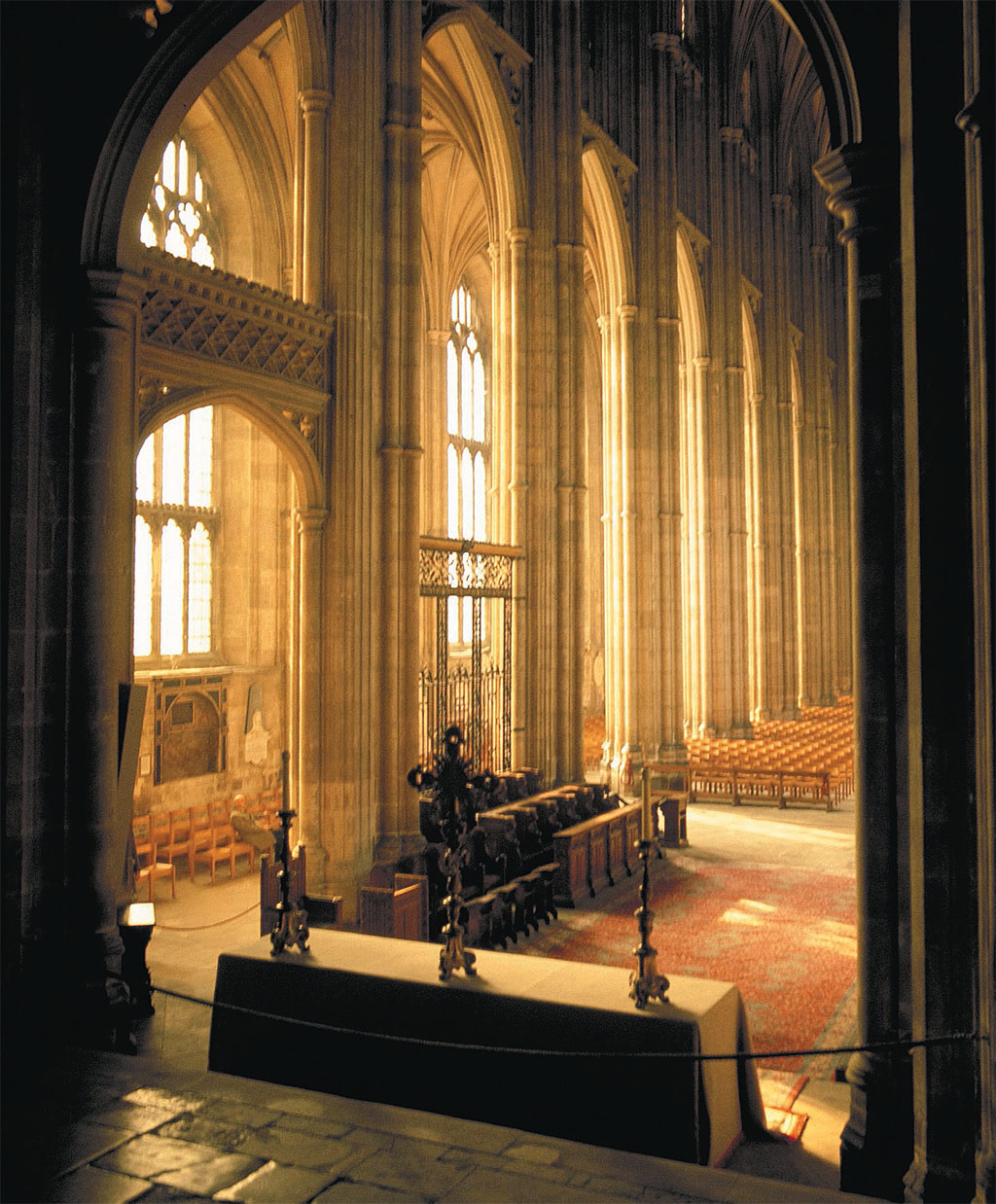

Throughout history, Archbishops of Canterbury have taken a leading role in the politics, social events and crises of their times. Each archbishop throughout the centuries has left some mark on the office. Of course, Thomas à Becket (1162-70) is famously remembered for opposing King Henry II over reforms in the church. For his opposition to the monarch, Becket was assassinated by four knights on December 29, 1170, within Canterbury Cathedral. T.S. Eliot brought the drama to the stage in 1935 in his well-known play Murder in the Cathedral, which continues to be performed in theaters today.

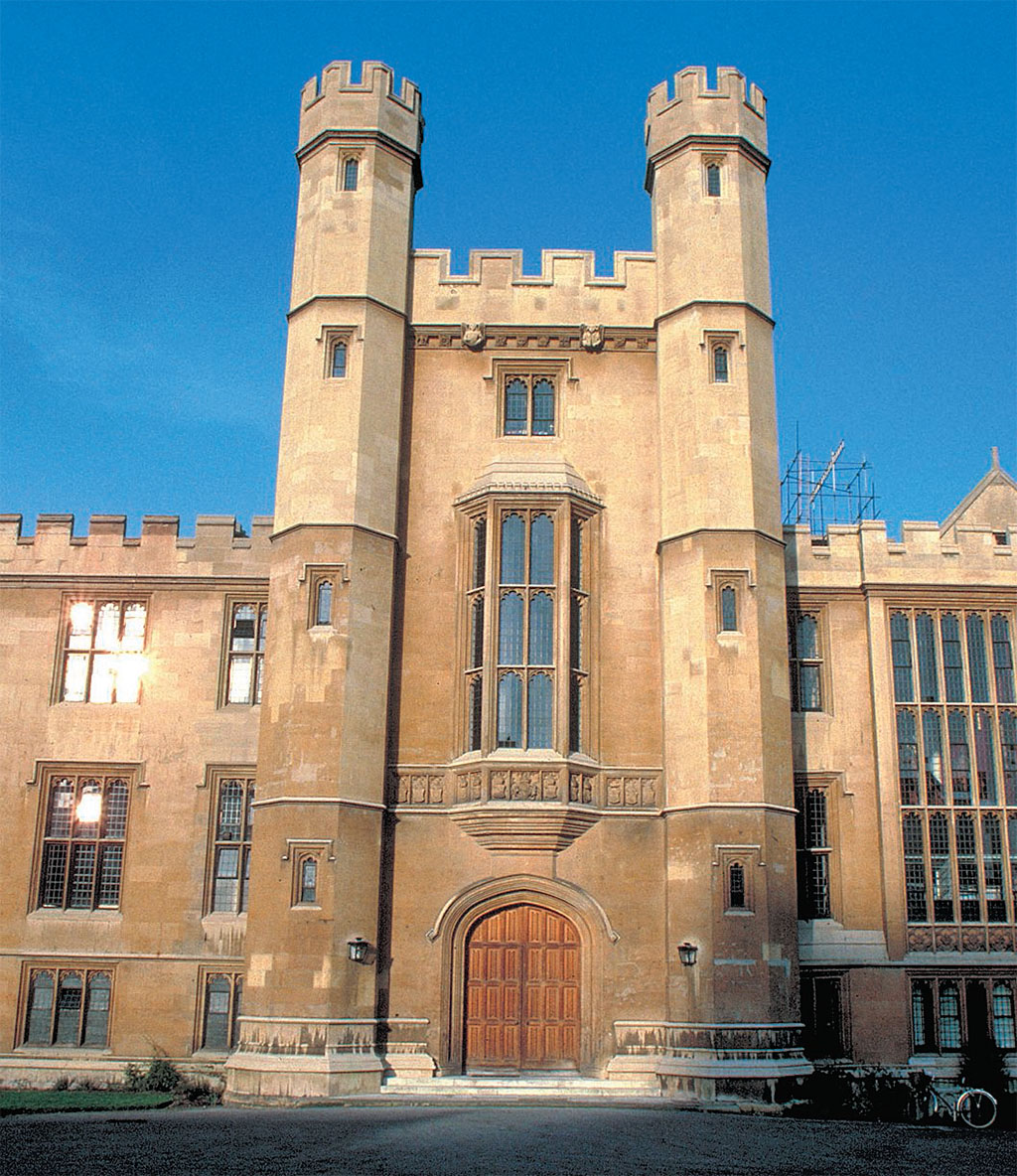

Archbishop Hubert Walter (1193-1205) completed the important acquisition in 1197 of Lambeth Palace as the London residence for the archbishopric, so necessary to bring the Church of England nearer to the seat of political and royal power in the capital city. While the spiritual center of the position remains firmly entrenched even today at Canterbury, Lambeth Palace, on the south bank of the Thames across from the Houses of Parliament, has been the administrative seat and home of the Archbishop of Canterbury since the 12th century.

[caption id="TheLordArchbishopofCanterbury_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Addtwo Design and Print Management

[caption id="TheLordArchbishopofCanterbury_img5" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Addtwo Design and Print Management

The sitting Archbishop of Canterbury also has lodgings in the Old Palace at Canterbury. Within Lambeth Palace is the Library, founded in 1610, which remains the record office for the history of the Church of England and maintains the correspondence and records of all Archbishops of Canterbury.

Moving forward in history, there was Archbishop William Howley (1828-48), who informed a young Victoria of her accession to the throne on the death of William IV in 1837. It was Howley who crowned her and presided at her marriage to Prince Albert. When the archbishop put the ring on the wrong finger at Victoria’s coronation it caused a delay in the ceremony of more than an hour.

Archbishop Geoffrey Fisher (1945-61) put a human face on the office when he crowned Elizabeth II in 1953, in the first coronation to be televised around the world.

While the Archbishop of Canterbury no longer has the right to license medical practitioners and has a much safer existence than some of his historic counterparts—William Laud (1633-45) was beheaded for high treason on January 10, 1645, the last Archbishop of Canterbury to be publicly executed—seven roles continue to fall to the position: (1) He is Diocesan Bishop of Canterbury and responsible for some 270 parishes in an area of nearly 1,000 square miles; (2) He is Metropolitan for the Southern Province of the Church of England, which means he has supervisory authority over all bishops and clergy in the 30 dioceses in southern England (the Archbishop of York having the same respective authority in the 14 dioceses in northern England); (3) He is Primate of All England in recognition of his lead ecclesiastical role in England; (4) He is leader of the Anglican Communion, which includes about 70 million members throughout the world; (5) He has an ecumenical role, taking the lead in respect of Anglican relationships with other Christian churches in the United Kingdom and abroad; (6) He plays an interfaith role by taking a lead in respect to Anglican relationships with other faiths; (7) He has a ceremonial role, officiating at coronations and state occasions—small in relation to his other roles, but important in its visibility to the public. An Archbishop of Canterbury is legally permitted to sign his name as Cantuar—Latin for Canterbury. Thus, Archbishop Rowan Williams signs his name as Rowan Cantuar; George Carey signed his name as George Cantuar.

What does the future hold for the Church of England? Lord Carey has expressed tremendous hope in the future, summing up his thoughts on the subject with great optimism. “Many people in the past have predicted the demise of the Church of England,” he said. “Matthew Arnold once declared, ‘The Church of England, no one can save.’ But we are still here, and the Church of England is the only truly national church remaining; its 16,000 parishes witness a determination to remain serving the people of this land. It will survive and prosper as long as it remains faithful to its founder, committed to his message and selfless in serving the people of these ‘green and pleasant lands’—and as long as it doesn’t take itself too seriously!”

[caption id="TheLordArchbishopofCanterbury_img6" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

[caption id="TheLordArchbishopofCanterbury_img7" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

[caption id="TheLordArchbishopofCanterbury_img8" align="aligncenter" width="479"]

Comments