OVER THE LAST YEAR OR SO, British Heritage has made much of the 400th anniversary of the English settlement of Jamestown: its origins as the brainchild of that great American hero Bartholomew Gosnold, and the 18-month calendar of events that culminated in Queen Elizabeth’s visit to Jamestown and America’s Anniversary Weekend.

Fewer folk have noticed that it is the tercentenary as well of another important milestone in America’s founding. Four hundred years ago this autumn, members of an outlawed Separatist congregation from Scrooby, Lincolnshire, fled their homes. They carried all they possessed some 30 miles toward Boston, pursued by authorities and armed soldiers. They sought new life in Holland, with freedom to worship as a church and live as a community. They were a determined people who had been building their church and their bonds for almost 10 years. We know them as the Pilgrims.

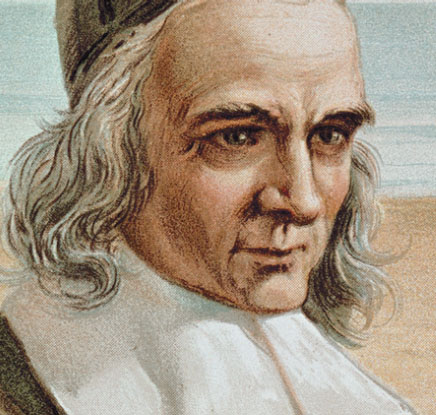

[caption id="ThePilgrimFlightforFreedom_img1" align="alignright" width="1024"]

DANA HUNTLEY

Just down the road a few miles from Scrooby, over the county line in northern Nottinghamshire, lies the little crossroads village of Babworth. In 1586 Richard Clyfton became rector of All Saint’s Church. Like many clergymen across the east of England, he had gone to Cambridge and been taught by those Protestant scholars who had fled the country under Bloody Mary and returned under Queen Elizabeth after spending years in the intellectual capitals of the Reformation: Geneva, Frankfort and Zurich. They came back convinced and determined to reform the Church of England: to rid the churches of the icons of Catholicism, to order public worship around the Word instead of the Sacrament, to teach holy living, to weaken Episcopal governance of the church and to loosen the bonds between the Church and the monarchy. We know them as the Puritans.

Under Queen Elizabeth I, Puritans flourished, particularly in East Anglia and the East Midlands, and spread into the Home Counties and London. While uniformity was the order of the day, and the upper echelons of the church hierarchy remained quite unmoved, at the grassroots level the local churches became increasingly Reformed in their theology, worship and world view.

By the late 1590s, Clyfton was one of hundreds of Reformed rectors in the region. People came from miles to hear him teach, including William Brewster, the 30-something bailiff of the Archbishop of York, Master of the Queen’s Post on the Great North Road and squire of Scrooby Manor.

It was no small matter in 1600 to devote your Sunday to closing up the manor house in Scrooby, gearing up the horses and traveling some seven or eight miles to Babworth to go to church. The teenaged William Bradford had a couple of miles farther to come from neighboring Austerfield. It was there at Babworth church that Brewster and the younger Bradford met and became lifelong friends.

After Elizabeth died, her successor, King James I, brought with him from Scotland firm ideas about monarchy, about the Church and his preeminent role in its governance and about his desire to be obeyed. At a conference at Hampton Court Palace in January 1604, a delegation of Puritans presented to James what has become known as the Millenary Petition because of the 1,000 Puritan clergymen who signed it. It was a roster of reforms the Puritan lobby sought for the Church and its governance. With the support of the powerful “establishment,” the King denied virtually their entire petition. In the subsequent clash of wills, several hundred Puritan pastors lost or resigned their livings—including Clyfton.

Taking away the living was taking away the pulpit and the parish rector’s livelihood, a virtual defrocking and excommunication from the ecclesiastical hierarchy. While it took away their church, however, it didn’t necessarily take away these recusant clergymen’s congregations. Many of these pastors kept meeting with their church families. They became Separatists. While Separatist congregations had existed prior to this time, it was in the immediate aftermath of the Millenary Petition that many independent congregations were born. In this country, we came to know them as Congregationalists.

When Clyfton lost his living and the congregation its pastor at Babworth, some in the north of Clyfton’s far-flung parish joined the Separatist church meeting under John Smyth at the Old Hall in Gainsborough some dozen miles to the east. The rest regrouped as a church, meeting at Brewster’s manor in Scrooby with Clyfton as pastor, John Robinson as teacher and Brewster as ruling elder.

The church at Scrooby was illegal. While it ostensibly met “in secret,” there was no way that the movement of people across the sparsely populated countryside and small villages went unnoticed. Besides, the artisans and farmers and their families who made up this congregation of 130 or so were all supposed to be in church somewhere else. Though you didn’t have to be quite regular in your attendance (apart from the requirements of your lord or employer), attendance at your parish Church of England was legally compulsory. This was a national church, by which all would worship and take the Sacrament.

However, as with any restrictive laws, the rub lies in the level and method of enforcement. Brewster was far too high profile for the law to ignore. In Scrooby, the Manor House where the renegade church met sits with its gates not 200 yards from the parish church. And Brewster, the resident gentry who was baptized there, did not attend. It was bound to draw attention.

By the autumn of 1607, the heat was on. Brewster resigned his positions as bailiff and postmaster and along with others ignored the summons of the High Court of Commission. Ultimately, he was fined, outlawed and a warrant executed for his arrest. The Scrooby church was broken up: some members were imprisoned, some had their houses ransacked, some lost their livelihood. That December they decided on short notice to leave for Holland, to join John Smyth’s congregation from Gainsborough and other English separatists already in exile. They fled toward Boston and a waiting ship.

They didn’t make it. The ship’s captain had betrayed them, and the Scrooby congregation was ambushed almost on the shore. The families were sent back home to Scrooby. The perceived ringleaders, including Brewster, Clyfton and Robinson, were imprisoned in Boston for a month. Their jail cells can still be seen in Boston’s old Guildhall.

A second attempt was made a few months later in the spring, this time from the Humber. The women and children traveled downriver, and the men made their way overland. The men had loaded aboard the Dutch ship when a large armed party was seen approaching; the captain weighed anchor and set sail. The Scrooby men helplessly watched as their families were taken captive. After two weeks of rough sailing, the men reached Holland. The women and children left behind, having neither homes nor support, proved more of a bother to authorities than anything else, and that summer they were allowed to join the men in Holland.

[caption id="ThePilgrimFlightforFreedom_img2" align="aligncenter" width="436"]

AKG

‘The Pilgrim congregation’s roots have never been promoted as a travel destination for Americans’

After a year in Amsterdam, the Scrooby congregation relocated to the university town of Leydon. Members established themselves as an independent church, and most practiced as craftsmen and artisans. Robinson and Brewster taught at the university. A decade later, however, the church people began to realize that their children were growing up Dutch, and yet they would congregation’s roots, those roots never have been promoted as a tourist destination. In part, this may be because of the location; Pilgrim Country is a little bit off the beaten track (and right on the Great North Road), lying in a tricorner where Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire and South Yorkshire all converge. In practice, that means that there has been no tourist agency to take charge.

Now, there is the Pilgrim Fathers UK Origins Association. This is one of those effective public-private partnerships in tourism promotion that the British do so well. The association aims to increase awareness of and to market the heritage of the Pilgrim Fathers both in local communities and internationally— particularly in the United States. The partnership is coordinating information on tourist services and campaigning to make historic sites such as the village churches open, accessible and user-friendly to visitors.

The association Web site at www.pilgrimfathersorigins.org has information on the history of the Pilgrim Separatists and on visiting the area. The Pilgrim Fathers UK Origins Association welcomes and encourages American visitors, and British Heritage readers to explore their early English roots.

Getting to Pilgrim Country takes a little planning and effort. The market towns of Gainsborough, Worksop and Doncaster are all within easy distance. Retford, however, on the Great North Road, may be the most practical starting point. For those who’d rather have someone else show them around, there are Pilgrim tours available from a local operator in Retford.

Comments