Mary anning’s seashells from lyme regis advanced our knowledge of the world

[caption id="ThePrincessofPaleontology_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

©The Natural History Museum, London

[caption id="ThePrincessofPaleontology_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

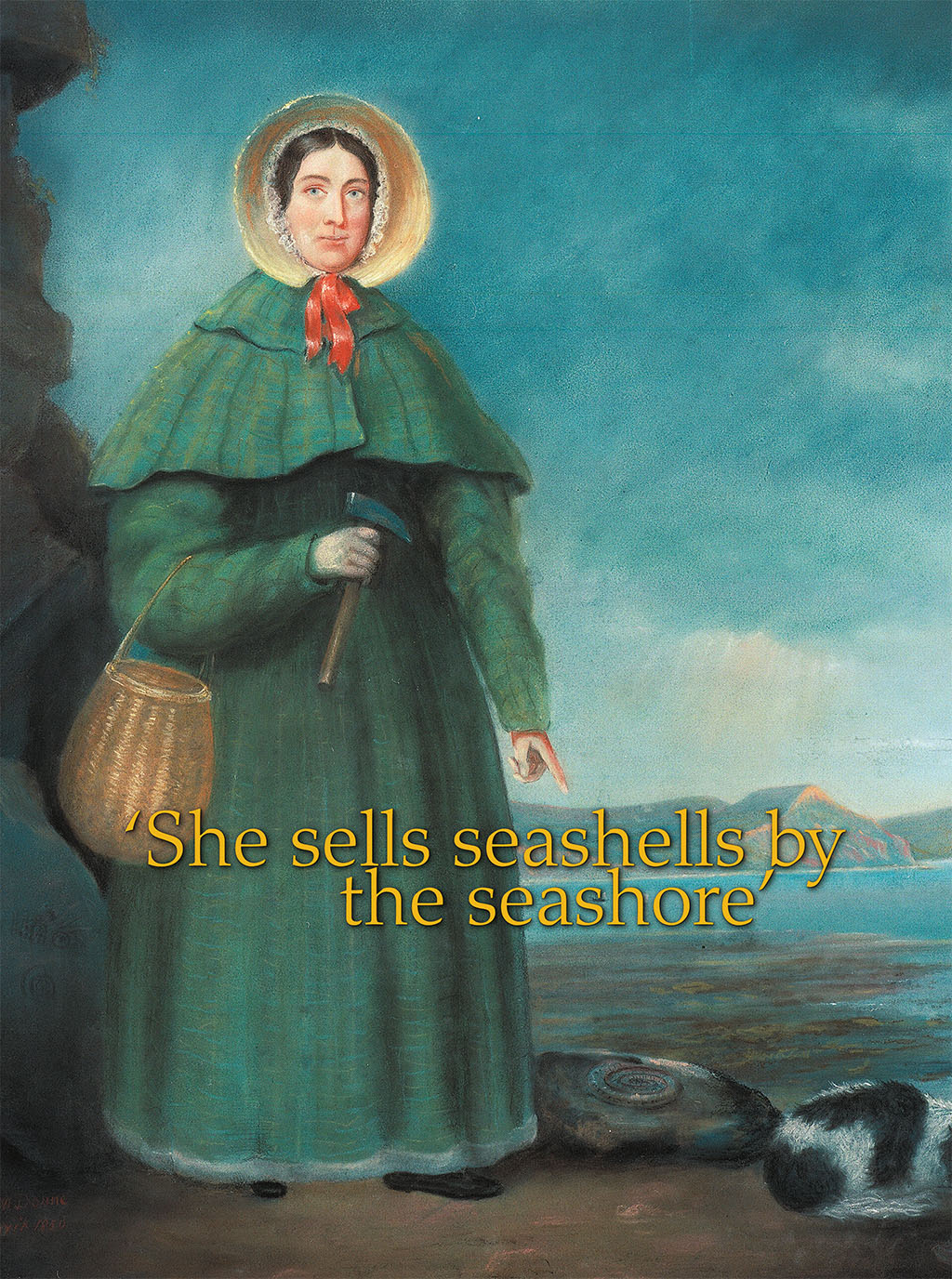

‘She sells seashells by the seashore’

during the early decades of the 19th century, Mary Anning (1799-1847) was a familiar presence on the beaches around Lyme Regis, a small harbor town on the shore of the English Channel in Dorset. “By all accounts she dressed for comfort rather than fashion, and must have looked a sartorial enigma in her battered top hat and cloak, with multilayered skirts to keep out the cold,” wrote Christopher McGowan in his book Dragon Hunters. Climbing on the region’s unstable cliffs, splashing about in the sea to see what the outgoing tide had revealed, Anning searched for fossils, the petrified remains of creatures that vanished from the earth long ago. Some of her finds contributed to a seismic shift in the way scientists looked at our planet’s history, but Anning was less concerned with science than in merely eking out a living by selling her finds from the family’s “curiosity shop.” In fact, local legend has it that Mary Anning was the inspiration behind the tongue twister, “She sells seashells by the seashore.”

Anning made her discoveries at a tremendously exciting time in the history of knowledge about the natural world. Science was still ruled by religion, and scientists struggled to fit their discoveries into the Bible’s story of Creation. The general wisdom, based on the genealogies from the Book of Genesis, held that Earth was about 6,000 years old. One theologian, John Usher of Cambridge, pinpointed it even more exactly. God, he said, had created the world at 9 a.m. on October 23 in the year 4004 BC.

Yet cracks were appearing in the accepted knowledge. The eminent French scientist Georges Cuvier (1769-1832) studied the bones of long-dead creatures and determined that some species from the past had vanished from the earth. The very process of fossilization implied that the planet must have been around for much longer than 6,000 years. How would it be possible to reconcile those discoveries with the Bible?

It was at this time that a number of people in Britain started to seriously study the petrified bones found embedded in rocks and began to realize that they came from animals unlike anything known on the planet. Around 1821 Gideon Algernon Mantell, a surgeon and fossil enthusiast, discovered some strange fossil teeth he believed came from a plant-eating reptile. In 1823 he dispatched the teeth to France for Cuvier to examine, but the Frenchman determined they were from a type of extinct rhinoceros or perhaps hippopotamus. Mantell disagreed. His views eventually won out, and he named his discovery iguanodon because he thought the tooth resembled that of a modern iguana.

Another English fossil hunter of the time was the Reverend William Buckland, Oxford’s first professor of geology and a true British eccentric. His menagerie included a hyena, as well as a pet bear that he sometimes dressed for public occasions in an Oxford cap and gown. Buckland had found fossil bones of a creature he named megalosaurus, yet he remained certain that such extinct animals were victims of the biblical flood. “Buckland believed that geological history reflected a gradual preparation of the earth for Man’s habitation and was optimistic that a scientific history of the earth would tally with scriptural records,” wrote Deborah Cadbury in her history of early paleontology, Terrible Lizard.

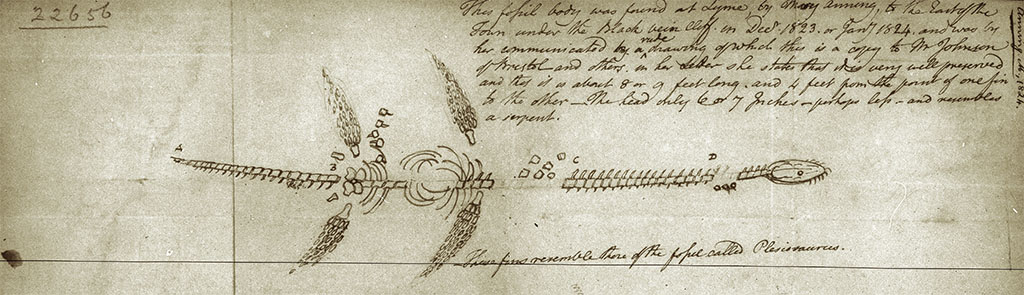

[caption id="ThePrincessofPaleontology_img2" align="aligncenter" width="820"]

Mary’s discoveries made her a local celebrity

Buckland and Mantell were both interested in Mary Anning’s discoveries. She was the daughter of Richard Anning, a poor carpenter in Lyme Regis, and his wife, Mary. Their town was perched on a hill above a tiny harbor, its most striking feature the long curving seawall called the Cobb. It was a wonderful place to find fossils. The area’s cliffs were composed of alternating bands of limestone and slate, known as Blue Lias, that dated from the Jurassic Period, when the region had been covered by primordial seas populated by many prehistoric beasts. The English Channel kept up a constant siege on the region’s soft cliffs, which often crumbled away to expose strange artifacts. The locals called fossil shells “ladies’ fingers,” while coiled shells that looked like the modern nautilus were “snake stones.” Sometimes collectors found stones that looked like pieces of backbones, which they named “verteberries.”

The Annings did not live easy lives. Their first child, also named Mary, died in a Christmastime accident at the age of 4 when her clothes caught fire. Another daughter was born six months later—on May 21, 1799—and the bereaved couple named her Mary as well. This Mary almost died at the age of 1 in another bizarre incident when a bolt of lightning struck her and her nurse while they were standing under a tree. The nurse and two other people died, but the baby, wrote McGowan, “upon being put into warm water, revived; she had sustained no injury. She had been a dull child before, but after this accident became lively and intelligent, and grew up so.” According to the era’s reasoning, perhaps only a literal bolt from the blue could account for the successes of a woman from Anning’s background.

Tragedy struck the family again in 1810 when Richard died following a fall from one of Lyme Regis’ cliffs, leaving his family saddled with debt. Suddenly the sale of the exotic finds from the local beaches gained greater importance. After young Mary sold a snake stone to a tourist for half a crown, she became a determined beachcomber. In 1811, the year after Richard’s death, her older brother, Joseph, found the fossil of what appeared to be a crocodile skull below the cliffs. He showed it to his sister, but a mudslide covered the find before she could excavate it. The sea takes, but sometimes it gives back, and a year later Mary discovered that the elements had exposed a fossil near the spot where Joseph had made his discovery. It was probably the same one. She worked diligently and soon uncovered the bones of an ancient sea creature that must have stretched 17 feet long. A wealthy local purchased the skeleton from Mary for 23 pounds, a small windfall for the impoverished family.

[caption id="ThePrincessofPaleontology_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

It would take years of study before scientists decided what, exactly, Anning had found. Sir Everard Home, somewhat of a scientific fraud, wrote a paper about the fossil in 1819. He wanted to call it proteosaurus. However, the British Museum had previously purchased the fossil and a curator there, Charles Konig, had already named it ichthyosaurus, which means “fish lizard,” and that name had precedence. “As for Mary Anning, she hadn’t the education or the position to name her finds, or to use them as an entrée to the male-dominated world of science,” wrote Cadbury. “She was not even named in the scholarly papers on her creature published in London. In her cottage by the sea or sitting on the shore at Lyme, she painstakingly copied out the learned articles in her own hand, making drawings and trying to grasp the language of the new science.”

Unlike “gentlemen” collectors, the Annings depended on Mary’s discoveries for their livelihood, and their fortunes ebbed and flowed depending on her success. The years before 1820 were very much an ebb tide. Things became so bad that a collector who had purchased fossils from the Annings, Lt. Col. Thomas Birch, auctioned his own collection to help the family. “I found these people in considerable difficulty—on the act of selling their furniture to pay their rent—in consequence of their not having found one good fossil for near a twelvemonth,” he wrote to Gideon Mantell. “I may never again possess what I am about to part with; yet in doing it I shall have the satisfaction of knowing that the money will be well applied.” The auction took place on May 15, 1820, in London and raised 400 pounds. Local gossips soon began talking about a sexual relationship between the 52-year-old Birch and the 21-year-old Mary.

Things did pick up for the Annings after the Birch sale. In May 1821, Mary found a 20-foot ichthyosaur. In August she found a 5-foot specimen, and in early 1822 she recovered one that was 9 feet long. Then, in December 1823, she made perhaps her greatest find, the bones of an altogether different species of sea creature. With the help of others from Lyme Regis, Mary struggled against the frigid sea to recover the fossil bones from their surrounding rock. She sold the skeleton to the Duke of Buckingham for 200 pounds. The animal was so strange—its neck so long—that some, even the great Cuvier, suggested Anning had faked it. When Konig at the British Museum studied the fossil, though, he had no doubt that it was genuine.

[caption id="ThePrincessofPaleontology_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

STAPLETON COLLECTION/CORBIS

Years before, scientists William Conybeare and Henry de la Beche had found some fossils that were obviously not from an ichthyosaur, and they speculated that some other strange beast had shared the prehistoric seas. When they saw Anning’s latest discovery, they knew they had been right. “The magnificent specimen at Lyme has confirmed the justice of my former conclusions in every essential point connected with the organization of the skeleton,” Conybeare wrote. It must have seemed as though Anning’s latest creature was a beast like the mythological Chimera, which had combined lion, goat and dragon. As Buckland described the creature, “To the head of the Lizard, it united the teeth of the Crocodile; a neck of enormous length, resembling the body of a Serpent; a trunk and tail having the proportions of an ordinary quadruped, the ribs of a Chameleon, and the paddles of a Whale.” He named the creature Plesiosaurus giganteus.

Anning continued to make important discoveries. In December 1828, she found another strange fossil, that of a flying reptile. Buckland purchased the specimen and named it Pterodactylus macronyx. He described it as “a monster resembling nothing that has ever been seen or heard-of upon earth, excepting the dragons of romance and heraldry.” Anning’s discoveries also contributed much to the study of coprolites—fossilized droppings—a subject Buckland found so fascinating that a friend tried to warn him off. “Though such matters may be interesting, it may be as well for you and me not to have the reputation of too frequently and too minutely examining faecal products,” he cautioned.

Mary’s discoveries made her a local celebrity. Geologists such as Mantell, Buckland and Richard Owen (the man who coined the term “dinosaur” in 1842) traveled to Lyme Regis to accompany her as she searched for fossils. An American geologist described her in 1827 as “a very clever, funny Creature”; a scientist from Germany dubbed her the “princess of paleontology”; and a mineralogist from Edinburgh who visited her in 1823 recorded, “Mary Anning’s knowledge of the subject is quite surprising—she is perfectly acquainted with the anatomy of her subjects, and her account of her disputes with Buckland, whose anatomical science she holds in great contempt, was quite amusing.” Nonscientists found her fascinating, too. Lady Harriet Silvester visited in 1824 and wrote, “It is certainly a wonderful instance of divine favour—that this poor, ignorant girl should be so blessed, for by reading and application she has arrived to that degree of knowledge as to be in the habit of writing and talking with professors and other clever men on the subject, and they all acknowledge that she understands more of the science than anyone else in this kingdom.”

Anning also knew perfectly well that men of science were capitalizing on her finds without giving her any credit. “She says the world has used her ill,” a friend noted. “These men of learning have sucked her brains, and made a great deal by publishing works, of which she furnished the contents, while she derived none of the advantages.”

Mary Anning died of breast cancer on March 9, 1847. Just a few months before, she became an honorary member of the Geological Society of London. Her life had been a constant struggle against poverty, but she nevertheless managed to make a name for herself in science despite her era’s bias against both her gender and class. Only posthumously did she receive the recognition she deserved. Today there is an Anning Road in Lyme Regis and exhibits about her discoveries at the local Philpot Museum. Also, a stained-glass window in the Lyme parish church honors the memory of the “princess of paleontology.”

Comments