Will it rally for a fourth term in Government?

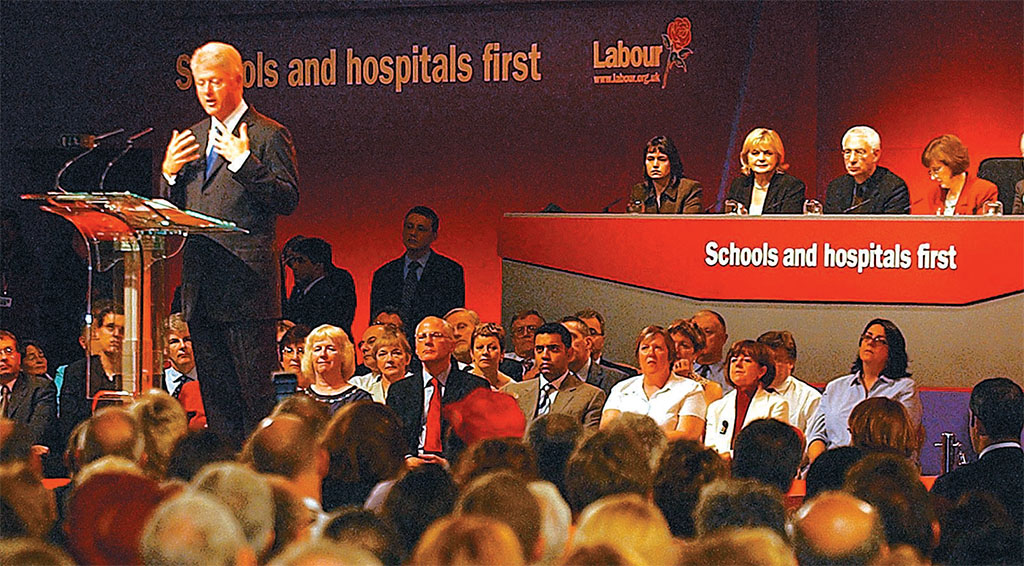

[caption id="TheRedRoseofLabour_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

© RUSSELL BOYCE/REUTERS/CORBIS

At the general election of May 1, 1997, the “repackaged” New Labour Party under 43-year-old Tony Blair secured its biggest-ever victory. A total of 418 Labour MPs won seats in the House of Commons, over 250 more than Conservatives and representing a majority of 179. After 18 years of Tory rule, the party’s vigorous “New Labour, New Life for Britain” manifesto had struck a chord with voters countrywide, and its subsequent two triumphs at the polls (June 7, 2001, and May 5, 2005) have given the party its longest continuous period in office. Emerging as a parliamentary pressure group in 1900, Labour had previously been in government for just 23 of its first 100 years.

But what most interested psephologists about the party’s 1997 landslide was an apparent upheaval in traditional voting patterns. As Andrew Thorpe notes in A History of the British Labour Party, Labour, historically the party of the working class and champion of its welfare, had always drawn strongest support from the heartlands of trade unionism and industry, geographically the industrial north of England, the coalfields (when they still existed) of south Wales, Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, parts of the Midlands, Scotland and London. Rural and middle-class areas, or anywhere in England south of the Severn-Wash line (demarked by the eponymous rivers) except for London, were practically unwinnable. In 1997 the North-South divide was significantly breached, and lower middle-class and skilled working-class voters swung heavily to Labour.

A durable breakthrough? And how far had New Labour traveled from Labour’s roots?

The working-class inspiration for the Labour Party derived distantly from the mid-19th-century Chartist movement for political reform and more immediately from the actions of late Victorian radicals keen to protect the rights of workers, in particular the trade unions. Although the Trades Union Act (1871) had given unions legal status, periodic assaults on their activities continued. Some unions managed to influence and support sympathetic Liberal (and occasionally Conservative) politicians, but Scottish Miners’ Federation secretary and socialist James Keir Hardie began a campaign for the creation of a separate labor party to specifically represent union and socialist interests in Parliament. Hardie won election as an independent labor MP in 1892, and he became first chairman of the Independent Labour Party (ILP), founded the following year.

In 1900 a coalition of interests—including various unions, the ILP, the Marxist-inclined Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and the socialist Fabian Society—formed the Labour Representation Committee (LRC). It wasn’t a party as such, and it had no members, simply affiliated organizations that supported it financially through fees. In the 1906 general election the LRC won 29 seats (two-thirds in northern England), changed its name and Keir Hardie became the first chairman of the parliamentary Labour Party—a name intended to be sufficiently broad to encompass all workers, not just grassroots manual laborers.

Many Labourites were pacifists, believing that peace was essential for (socialist) progress, and the party’s leader, James Ramsay MacDonald, resigned in opposition to World War I. Yet war proved a catalyst for raising Labour’s profile, giving those MPs who entered the 1915-18 coalition government their first taste of ministerial office. When the Liberal Party collapsed in 1922, Labour stepped from its shadow and took its place as the major alternative to Conservatism. It had transformed from the turn-of-the-century pressure group into a serious party with, since 1918, a new constitution and organization. Local constituency parties now allowed individual membership as well as the affiliation of unions and socialist parties. And Labour formally adopted a socialist policy of “common ownership of the means of production” (i.e., nationalization of industry). This so-called Clause Four drew little comment at the time but became a touchstone of party principle that was to cause much hand-wringing in the future.

In 1924 Labour briefly formed a minority government under its returned leader, Ramsay MacDonald. But the 1920s also brought two major threats to its growing popularity. The first was union militancy and strikes, culminating in the 1926 General Strike, all of which led to distrust of Labour and its connections with the unions. In fact, the Labour leadership was horrified by events. The second was the “Red Scare.” At a time of Bolshevik revolution in Russia and spreading communism, sections of the general public were wary of British socialism.

[caption id="TheRedRoseofLabour_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JOHN GILES/PA/EMPICS

Labour’s second minority government (1929-31) foundered on the world economic crisis following the October Wall Street crash; the “party of full employment” proved ineffective against rampant joblessness. When Ramsay MacDonald formed a coalition National Government with Conservatives and Liberals to face the crisis together, he was expelled from Labour. Outraged members could not believe that a founding father—he had been the first secretary of the LRC and the Labour Party—could “betray” the cause in this way.

The 1930s were a decade of disappointment at the polls for Labour, but also a time to work on policy and party discipline. Invited to join Winston Churchill’s wartime coalition government (1940-45), Labourites acquitted themselves well and regained much credibility that had been lost in 1929-31. Labour’s leader, Clement Attlee, chair of the Food and Home Policy Committee, skillfully oversaw the apportioning out of scarce resources, while Ernie Bevin showed outstanding ability handling unions and manpower as minister of Labour and National Service. The public image of socialism and trade unionism improved.

At the 1945 election, Labour captured the postwar public mood for change with its “Let Us Face the Future” manifesto and pledge to destroy the five “evil giants” of want, squalor, disease, ignorance and unemployment. The party’s landslide victory of 393 seats (and 48 percent of votes) meant that for the first time it had MPs representing every region of the country. It also had its first majority government—and unprecedented opportunity to implement its program of reform and the welfare state called for by the 1942 Beveridge Report.

The Attlee government proceeded to set a high watermark of Labour social policy achievement and, with ensuing Labour ministries until 1951, altered the complexion of Britain. The jewel in the crown was the establishment in 1948 of the National Health Service, “free at the point of use.” The National Insurance Act (1946) improved social security: Workers paid a flat-rate contribution and became eligible (with their wives) for sickness, unemployment and funeral benefits plus flat-rate pensions. The National Assistance Act (1948) provided financial aid to those lacking any other source of income.

A wide program of nationalization (“common ownership of the means of production”) was also implemented, including the Bank of England, civil aviation, cable and wireless, coal, road haulage and rail, gas and electricity and eventually iron and steel—in all, around 20 percent of the economy. The Labour leadership was in harmony with the unions, against a background of full employment and rising living standards among the working class. Given the challenging circumstances of the postwar era, it was a remarkable socioeconomic record, made possible in no small part by the provisions of Lend-Lease, U.S.–Canadian loans and the Marshall Plan.

Foreign policy was dominated by the Cold War and the establishment of NATO (1949), formally allying Britain and America. But Labour was more ambivalent over rapprochement with continental Europe, preferring an internationalist outlook to taking part in discussions that would eventually lead to the formation of the European Economic Community. Labour has since warmed to the European Union.

After so much innovation, the Labour Party seemed to lose steam, and in 1951 it lost office to the Conservatives, remaining out of power until 1964. It was, however, a measure of the success of Labour’s administration that the Conservatives, though advocates of private enterprise, generally left intact the mixed economy and welfare state they had inherited.

When Labour returned to power (1964-70 and again 1974-76), it was under the pipe-smoking “man of the left,” Harold Wilson. The government struggled with inflation, and economic growth was hampered by a refusal to devalue the pound until 1967. But Labour did make progress in its cherished aim to make educational opportunities less exclusive through the comprehensive school system.

By 1970 the 11-plus exam and grammar schools had vanished from many areas, and around a third of secondary school pupils in England and Wales attended nonselective comprehensives. The Wilson era is also popularly remembered for liberal—some said morally soft—legislation on hitherto taboo subjects: easing divorce, legalizing homosexuality and abortion. Capital punishment was abolished.

When Wilson retired from office, centrist James Callaghan took over and was prime minister from 1976-79. Again, the Labour government struggled with inflation, combating it by trying to restrict pay rises. Bitter labor disputes followed, culminating in the notorious 1978-79 “Winter of Discontent” of power cuts and strikes, and widespread public feeling that Labour could not handle the unions. The party lost the 1979 election and entered a long period in opposition to the Conservatives from 1979-97, during which three further elections were lost.

Under its three leaders from 1983, Welshman Neil Kinnock, Scot John Smith and Englishman Tony Blair, Labour’s fight for revival and popularity became systematic and ruthless. While Margaret Thatcher and the ruling Conservatives fought striking miners and neutered “troublesome” unions, Kinnock was moving Labour back to the right and sidelining extremists in order to project a more moderate image and divest the party of its more radical policies. Symbolic of these changes was the replacement of the party emblem in 1986 from the red flag (“it shrouded oft our martyred dead,” in the words of the party anthem) to the friendlier red rose.

Further changes included ending Labour’s commitment to unilateral disarmament (a tradition harking back to the pacifism of its early leaders but unpopular with voters), as well as high taxation and old-style nationalization, which in practice had largely become discredited. Labour still lost the 1992 election to John Major’s Conservatives. Kinnock resigned.

“Modernizing” and repackaging continued under John Smith, notably in the reduction of trade unions’ influence by replacing their traditional block vote within the party; from now on there was to be One Member One Vote (OMOV), which removed direct union representation in parliamentary selections.

Tragically, Smith died of a heart attack, aged just 55, in May 1994. Tony Blair, at 41 Labour’s youngest-ever leader, succeeded him. Blair’s rise had been meteoric. An Oxford graduate and practicing barrister until he entered Parliament in 1983, he quickly gained a reputation as a modernizer. He was photogenic, smooth and media friendly. A chief architect, indeed the public embodiment, of “New Labour,” he convinced the party to “update” Clause Four of the party’s constitution. Nationalization had become unpopular, but Labour traditionalists had clung to Clause Four as an article of faith over the years, and previous attempts to modify it had foundered. In place of the socialist policy of “common ownership of the means of production,” Clause Four is now more vague.

Labour worked hard to convince industry it could run a sound economy. It was swept to power in 1997 on a manifesto centered on five priorities: education, crime, health, jobs and economic stability.

Two elections and nine years later, highlights of the Blair administrations include the following: in work/welfare, the introduction of a national minimum wage, and in constitutional matters, devolved power to the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly and partial reform of the House of Lords by which all but 92 of the 750 hereditary peers lost their right to sit in the Upper House. (Blair wanted all to be removed but agreed to a compromise.) There have been torrid debates about education and the future of the National Health Service. The historic Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland was delivered and—controversially—Labour involved Britain in the war in Iraq.

The future? At the time of writing, Labour has been the subject of a series of political, financial and sexual scandals. Recent opinion polls have shown the historical North-South voting divide has reasserted itself, and Blair, from breaking all records for public approval nine years ago, is now rated the most unpopular Labour prime minister of modern times. History will take true stock—and show in perspective the latest developments in the influence on the party and its fortunes of trade unions, socialism and modernism.

[caption id="TheRedRoseofLabour_img2" align="alignleft" width="920"]

Comments