Still making maritime history at Portsmouth’s Historic Dockyard

DANA HUNTLEY

AFTER YEARS OF PREPARATION, the long-awaited new Mary Rose museum opened this summer in the Historic Dockyard of portsmouth, right adjacent to nelson’s famous HMS Victory. The £37-million ship-shaped building preserves what was King Henry VIII’s flagship in a state of the art, climate-controlled hall, as well as provides an excellent exhibition of the ship’s history, artifacts, people and the story of its resurrection from the solent, where it sank in 1545.

Visitors pass through four levels of the ship’s decks, with the conserved starboard hull of Mary Rose on one side and the portside reconstructed from artifacts discovered with the ship when it was recovered in the early 1980s. After almost 500 years, Mary Rose has come home to portsmouth, where it was built.

For centuries, it seems like England was always at war with France. They certainly were during the reign of the colorful King Henry VIII. When young King Henry took the throne in 1509, the Tudor monarch dearly wanted to play in the big leagues of European politics, to be considered the equal if not the greater of the significant players on the 16th-century Continental stage. Alas, the navy King Henry inherited consisted of only two sizeable ships, and so in 1510 the king commissioned the Mary Rose.

COURTESY OF PORTSMOUTH HISTORIC DOCKYARD

COURTESY OF PORTSMOUTH HISTORIC DOCKYARD

COURTESY OF PORTSMOUTH HISTORIC DOCKYARD

[caption id="TheResurrectionoftheMaryRose_img4" align="aligncenter" width="560"]

COURTESY OF PORTSMOUTH HISTORIC DOCKYARD

COURTESY OF PORTSMOUTH HISTORIC DOCKYARD

The Mary Rose was meant to be the equal or master of any known battle ship alfoat, and it was, displacing 700 tons or so and carrying 80 to 90 guns. Built in portsmouth, it took the hardwood of an estimated 600 oak trees to provide her timber. Mary Rose was commissioned and put to sea in 1512, and did exactly what the shrewd King Henry intended.

The powerful ship led a rejuvenated and potent english feet along the Atlantic coast and gave Henry new muscle with his neighbors. For 30 years, Mary Rose served as the English flagship and one of the largest ships in the feet.

[caption id="TheResurrectionoftheMaryRose_img6" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

[caption id="TheResurrectionoftheMaryRose_img7" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

[caption id="TheResurrectionoftheMaryRose_img8" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

King Henry had aligned himself by marriage and trade to the Spanish Habsburgs and the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian in a league against the French. It was a hot-and-cold war for a generation. Way leads on to way, of course, and in 1545 England and France were hard at an active war by land and sea. Coastal defenses had been erected from the Thames estuary south along the english Channel and west all the way to Cornwall. None of these new fortresses was more important than Southsea Castle, guarding the approach to Portsmouth Harbor, home base of the English fleet.

In the summer of 1545, the French amassed an armada at the mouth of the seine in an attempt to launch an invasion of England. A battle formed as the English 80-vessel feet left Portsmouth Harbor to meet the galleys leading the French Fleet of 128 ships. King Henry VIII watched the battle develop and play out in the waters between him and the isle of Wight from the battlements of Southsea Castle. In fact, after an indeterminate skirmish on July 18, the king dined shipboard with his admiral, Viscount Lisle.

In action the next day, when the fleets engaged in what became known as the Battle of the Solent, the English ultimately chased away the French. Unhappily, the fate of Mary Rose was not so fortunate. Though the exact cause remains unknown, a damaged Mary Rose listed and sank with alarming speed in front of King Henry’s very eyes. It may have been a combination of wind, battle wounds and poor helmsmanship, but Mary Rose dropped fast with almost 400 lives lost with her. Only some 30 sailors aboard lived to tell the tale. And there, at the bottom of the oxygen-rich, silt-dense Solent Mary Rose lay, to waste away with history, for 437 years.

THE SOFT SEABED layered on hard clay provided a perfect resting place for Mary Rose. Its starboard side sank deep in the protective mud, while its port was exposed to the currents and the natural depredation of marine organisms. Over the centuries, the port side of the hull and any artifact of organic origin or iron simply wasted away into the moving seawater. The intact starboard side of Mary Rose and much of her shipboard contents submerged in the silted Solent’s seabed soil survived the centuries amazingly intact.

Fishermen discovered the location of the shipwreck in the 1830s and there was a limited salvage attempt at the time. The modern search for Mary Rose was engaged by the Southsea branch of the British Sub Aqua Club, whose search led to the discovery of the ship in 1971. Following years of publicity and underwater exploration, the Mary Rose Trust was formed in 1979 and active work begun on making the Mary Rose rise again.

[caption id="TheResurrectionoftheMaryRose_img9" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

COURTESY OF PORTSMOUTH HISTORIC DOCKYARD

A VISIT TO MARY ROSE

Right on the waterfront of Portsmouth’s harbor, the Mary Rose is ticketed with a timed entrance at the Historic Dockyard. Its £17 admission ticket is dear. A combined site ticket to all the Historic Dockyard ships and attractions, including HMS Victory, HMS Warrior, the Museum of the Royal Navy and a cruise of Portsmouth Harbor, though, is only £26—and good for a year.

If you’re making a purposeful trip to Portsmouth from London, it is easiest to do by train, with hourly departures from London Victoria to Portsmouth Harbor. The Historic Dockyard is just outside the train station.

After three seasons of intensive archeological work underwater, in October 1982 a special lifting frame, hull and cradle built around the ship brought Mary Rose to the surface to worldwide attention. It remains perhaps the most complex and ground-breaking project ever undertaken in marine archaeology. Mary Rose was conveyed into temporary shelter in Portsmouth Historic Dockyards; salvage work at the site continued, with a staggering total of more than 19,000 artifacts retrieved from the Solent floor; and the painstaking task of conservation begun.

The next summer, the remains of Mary Rose went on display to the public under a tunnel of tarpaulin in a huge temporary marquee. A cold mist filled and chilled the air with a spray of 35 to 40 degree filtered water constantly bathing the extraordinary timber wreckage of the once state-of-art warship. For more than 30 years, that incessant shower continued over Mary Rose. Pure water became a dilute solution of polyethylene glycol in a long-term conservation plan to seal the moisture within the molecular structure of the ancient wood.

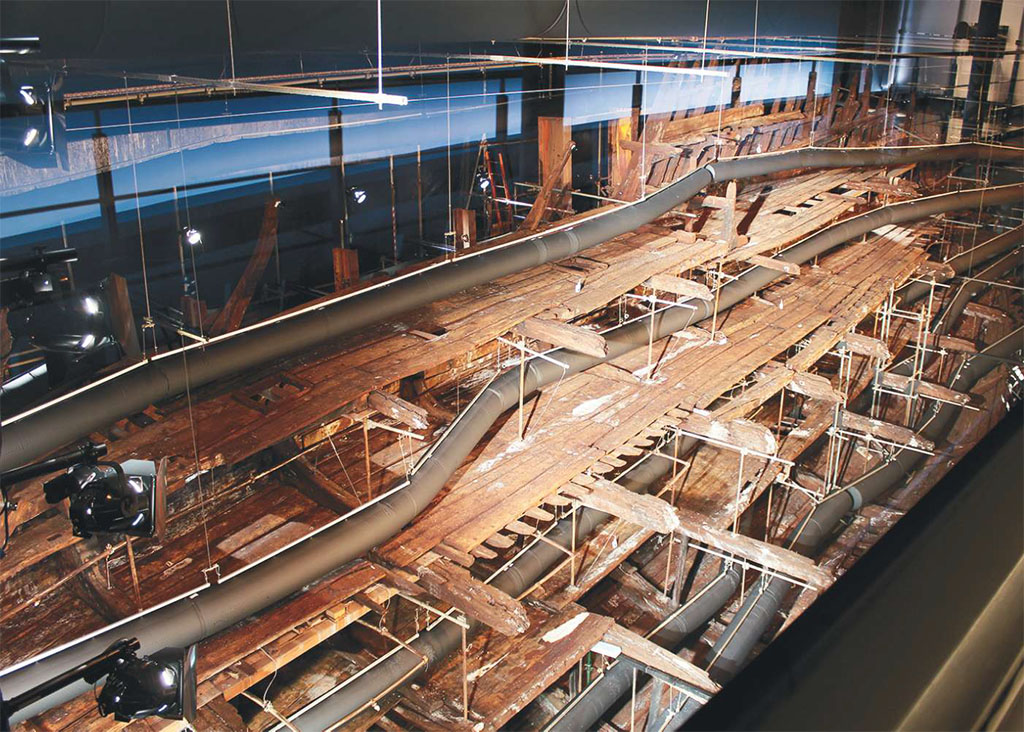

That constant spraying of water and glycol has done its job after 30 years. Now, large black air ducts run the length, beginning the process now of drying Mary Rose out. It’s the last step in the conservation program and is expected to be complete in 2017. Over these past 30 years, researchers have studied, catalogued and conserved the thousands of artifacts recovered from the Solent seabed. Though artifacts exposed to the sea disappeared long ago, the preserving silt yielded leather, wood, bone and metal held intact in time. There were bronze cannons and culverins, barrels that were once stocked with victuals, a goodly stock of longbows and the skeleton of a young dog thought to be aboard as a ratter. Many items were the personal belongings of sailors—combs, shoes, musical instruments, sewing kits, games and rosaries.

Most of the 400 men lost on the Mary Rose are unknown by name. From findings in the carpenter’s cabin, the barber-surgeon’s cabin and elsewhere, however, researchers have been able to piece together the lives of five of the crew aboard Mary Rose. Their stories and their belongings are on display at the museum as well.

Mary Rose is drawing rave reviews from the more than 300,000 visitors who have made their way to the new museum in its first six months. After all, it is the only 16th-century warship on public display anywhere in the world.

Comments