Still Tory After All These Years

[caption id="TheTrueBlueConservativeParty_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

© FERRUCCIO/ALAMY

The Conservative Party is the oldest of its kind in Britain and perhaps in the world. As its name, first adopted in the 1830s, suggests, its original purpose was to preserve the status quo, in this case the traditions that gave Britain its social and political character: the constitution; the monarchy; the aristocracy and its landed interests; the Houses of Parliament, especially the Lords; the established, Anglican church; and the union with Ireland.

Inevitably, with such an agenda, the party was for a long time regarded as less progressive than its Parliamentary rivals, the Liberals or, much later, the Labour Party. Conservative beginnings typified this image, which first arose after 1679, when the Tories, as they were then known, successfully resisted attempts by Protestant Whigs (Liberals) to eject the Catholic James, Duke of York—the future King James II—from the succession to the throne. Their success was short-lived, however. In 1689 William of Orange, a Protestant from Holland, replaced James II on the throne.

The Conservatives’ image as guardians of tradition commended them to the later Hanoverian kings, George III and George IV, whose own political influence was much greater than Queen Elizabeth II enjoys today. With this royal backing, the Tories were able to monopolize the governance of Britain during both their reigns, between 1760 and 1831. However, by the early 19th century, progressive ideas were fast invading the political scene as issues arose demanding urgent redress. Among them were the slave trade, the illegal status of trades unions, and laws banning Catholics from public and political life.

Despite vigorous efforts designed to fend off reform, the Conservatives were forced to give way over all these grievances. The end of Tory domination was signaled first by defeat in the election of 1831, and next by the Great Reform Act of 1832 that the victorious Liberals lost no time steering through Parliament. The act intruded on almost everything the Tories held most dear. It broke into the aristocratic monopoly in Parliament, by giving the middle class votes and a voice in government for the first time. The act also ensured fairer and more widespread representation for the industrial towns, thereby reducing the power of the rural interests the Tories had always favored.

[caption id="TheTrueBlueConservativeParty_img1" align="aligncenter" width="556"]

STEFAN ROUSSEAU/PA

The Great Reform Act forced the Conservatives to rethink ways and means of fending off further changes that might inflict more damage on the established institutions they were sworn to defend. Their solution was something new to British politics—formal party organization that would place electoral management on a permanent footing. One result was the establishment of the Carlton Club in central London. By 1833 the club already boasted 800 members. Two years later, the first fulltime party agent, Francis Bonham, was appointed, and the club formed a permanent committee to deal with electoral matters.

The Carlton Club served as a rallying point for the Conservative Party, and a venue for coordinating press campaigns and formulating the tactics to be used in Parliament. Beyond London, the Carlton was emulated by Conservative Associations that were set up throughout Britain to handle the nuts and bolts of getting candidates elected to Parliament. The associations handled the registration, selection and sometimes the financing of candidates and the canvassing of votes in their support. Conservative voters were encouraged to reduce the chances of their rivals in elections by questioning the right of Liberal voters to the franchise. This dirty, but legal, trick often worked, for the Liberals remained a loose, unorganized coalition until as late as 1868. As a result of these tactics, the Conservatives increased their voter base, so laying the basis for future election victories.

After 1832, however, Liberals as well as Conservatives entered unknown political territory, as newly enfranchised voters agitated in their own interests. This was how the protectionist Corn Laws, first passed in 1815 to prohibit the importation of wheat, emerged 25 years later as a political cause celèbre. The Corn Laws raised bread prices until ordinary people were unable to pay them. The laws were also blamed for causing the agricultural and industrial depressions that occurred during and long after the 1820s. Most significant, the Anti-Corn Law League, founded in 1839 and centered on the Lancashire cotton industry, identified the hated legislation as a symbol of aristocratic privilege.

[caption id="TheTrueBlueConservativeParty_img2" align="aligncenter" width="791"]

© FERRUCCIO/ALAMY

Diehard Conservatives put up a strong fight to retain the Corn Laws, but Conservative Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel realized how dangerous the situation had become. All the ingredients were present for violent agitation, if not revolution—the chance of widespread starvation, the risk of mass unemployment and subsequent unrest. The Corn Laws had to go. The laws were repealed in 1846, and were replaced by free trade, but the split that occurred between protectionists and free traders within the Conservative Party brought Peel’s government down.

The struggle over the Corn Laws brought home another lesson to the Conservatives: They were still overly identified with rural interests and aristocratic privilege. It was imperative to change this traditional emphasis, and a start was made in 1867, when the Conservative government elected the previous year extended the franchise to householders paying rates, lodgers paying £10 a year in rent, landowners whose land was valued at £5 and over, and tenants paying annual rent of £12. The idea was to improve the party’s prospects by encouraging previously excluded sections of society to vote Conservative. The message obviously took a while to get through, for in 1868 the Conservatives, now led by Benjamin Disraeli, were defeated at the polls and went into opposition in Parliament. Disraeli, however, was a committed modernizer, and in 1870 he established Conservative Central Office as a headquarters from which support for the party could be orchestrated.

[caption id="TheTrueBlueConservativeParty_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

PA

Now, the Party drew its support across all communities and classes, both urban and rural.

After the Conservatives were returned to power in 1874, with Disraeli as prime minister, he embarked on a groundbreaking program of social welfare that contravened one of the Conservatives’ greatest hates—state interference in the lives of the people. However, as Disraeli readily realized, government initiatives were the only way to achieve improvements in the welfare, health and working conditions of the working class. Slum housing was modified by better homes for skilled workers, a 10-hour working day was established on weekdays with Saturday afternoons free for leisure or rest, polluted rivers were cleansed and drainage systems were improved.

The difference Disraeli’s reforms made in modernizing the Conservative Party was very considerable. By the time he left office in 1880, the party had been almost totally transformed. Now, it drew its support across all communities and classes, both urban and rural, and among the poor as well as the rich. Disraeli had also introduced a new mindset into the Conservative ranks. Before long, many titled or wealthy Conservatives came to the House of Commons believing that public service, in Parliament or out of it, was less a matter of catering to their own self-interest and more a duty that required them to pay for the privileged status they had acquired at birth.

As time went on, other shifts of emphasis began to appear in the Conservative Party. After the disintegration of the Liberal Party in 1922, the Conservatives were confronted with a new political rival, the Labour Party, whose emphasis was firmly on working-class welfare and the socioeconomic issues that affected it.

After the end of World War I in 1918, British political life was increasingly concerned with economic depression, the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, the spread of communism, pugnacious trade unions, welfare issues and demands for greater equality. The Conservatives required to tackle these issues were no longer the titled, landed grandees of the past; the funding of the party was now handled by businessmen, entrepreneurs, and industrial and commercial companies. With this, the middle classes had largely assumed control. The party was also supported by almost one-third of the working-class electorate.

After World War II, the British electorate was convinced that, of the two major political parties, Labour was more likely to implement the provisions of the Beveridge Reports of 1942 and 1944 that contained a blueprint for a postwar welfare state. The result was a landslide victory for Labour in 1945, when it won 393 seats to the Conservatives’ 197. Although the welfare state put in place by Labour in mid-1948 went against every Conservative instinct, the proportions of their defeat obliged Tories to come to terms with this new political reality. They agreed to a consensus, built around a managed economy, full employment, a National Health Service and other forms of state-controlled welfare, which protected people from the cradle to the grave.

Consensus politics, as this arrangement came to be called, lasted for almost 30 years through four Conservative and three Labour governments. Ultimately, in the 1970s consensus came to an end in the face of increased inflation, bitter labor disputes, rising unemployment and declining trade figures. In this disputatious atmosphere, voters became attracted to the hard-line solutions promised by the Conservative government led by Edward Heath, elected in 1970. Heath’s administration proved much more conservative than any since World War II, advocating a competitive rather than a state-managed economy and cuts in the social services. Heath lasted only four years before an oil crisis, rising inflation and a long miners’ strike forced him out of office.

[caption id="TheTrueBlueConservativeParty_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

© MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARY

Margaret Thatcher, Heath’s successor as party leader in 1975, did much more than simply go where he had gone before. She was something new in British prime ministers, an ideologue who knew precisely the sort of Britain she wanted. Thatcher envisioned Britain as a place where taxes were low, dependence on welfare was reduced, “lame duck” companies in trouble would not be rescued by government, state ownership would lapse and the people would be “set free” to use their own initiative for their own benefit.

At first, all went well after Thatcher and the Conservatives won the election of 1979. The trade unions, which had bullied both Labour and Conservative governments in the past, were tamed by laws limiting their power to orchestrate industrial action. This pleased voters, who had been greatly inconvenienced by strikes and stoppages over the years. They became less sure, though, about the rest of Thatcher’s policies, which involved the deregulation of business activity, a free-market approach and the privatization of public utilities. The result was not the Conservative dream of setting the people free from state interference so they could follow their own star. A recession that was already biting hard brought high unemployment and a severe reduction in Britain’s industrial base.

After it was introduced in 1990, the poll tax, a charge adults paid to finance local government, caused protests and riots on a scale rarely, if ever, seen in Britain. Soon afterward, another crisis erupted over Thatcher’s refusal to agree to greater economic and monetary integration into the European Union, which Britain had joined in 1973. This alienated some of her more pro-European colleagues. As a result, Thatcher was deserted by her cabinet, and on November 13, 1990, she was voted out of office in a leadership contest.

Under her successor as prime minister, John Major, the Conservatives took to factional fighting, and several ministers and MPs were involved in sex, financial and political scandals. Under this weight, the reputation of the Conservative Party suffered disastrous decline. On May 1, 1997, after 18 years in power, the Conservatives went down to a landslide defeat at the hands of Labour and its charismatic leader, the 43-year-old Tony Blair. Through elections in 2001 and 2005, the Conservatives still had not recovered.

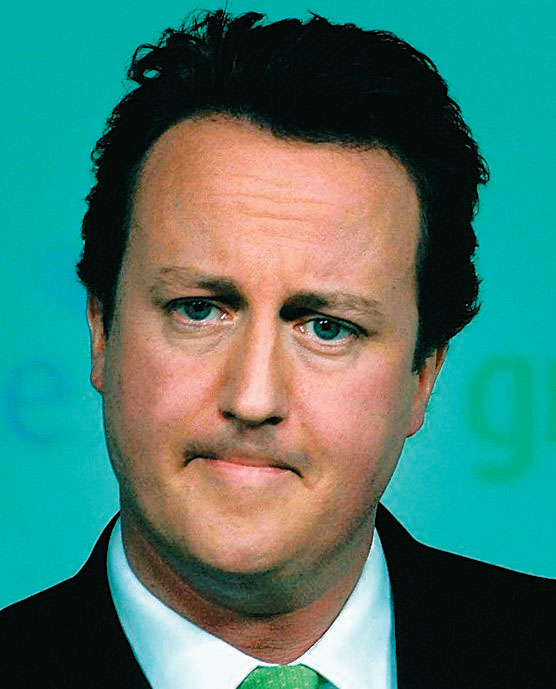

Each of these defeats was followed by the resignation of the Conservative leader—John Major in 1997, William Hague in 2001 and Michael Howard in 2005. The fate of Major, Hague and Howard—and Edward Heath before them—indicates to David Cameron, the present Conservative leader, that the party must make a drastic change of direction if it is to mount a proper challenge to Labour the next time around. Cameron, who was elected leader last December, caused something of a sensation soon afterward when he announced that he meant to discard the monetarist legacy of Margaret Thatcher and take his cue instead from the reformist Tony Blair. Cameron has infuriated the Conservative right wing with his talk of moving the party back toward the “center” ground in politics and reintroducing “compassionate” conservatism. With the next general election three or four years away, it remains to be seen whether the party will back its new leader and his new Conservative vision.

Comments