A MEMOIR OF WORLD WAR II A MEMOIR OF WORLD As the German Luftwaffe set its bombsights on London, many families with children fled the city for the relative safety of England’s countrys ide.

[caption id="ThemForeignersUpfromLunnon_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Courtesy of Amersham Museum, UK.

MY UNCLE LEON had a serious, apprehensive look on his face when he came to fetch me from the playroom, where I was reading. “Put the book down,” he said, “and come and listen to this….”

[caption id="ThemForeignersUpfromLunnon_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

THE FRANCIS FRITH COLLECTION,SP3 5QP

I followed him into the living room, where my parents were sitting by the radio. Like people all over Britain, we were waiting for the prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, to speak to the nation. It was 11:15 on Sunday morning, September 3, 1939. Mr. Chamberlain’s voice as it came through from the prime minister’s official London residence at 10 Downing St. was thin and reedy.

He sounded despondent, and with good reason. Two days earlier, the forces of Nazi Germany had invaded Poland, and with France, Britain was pledged to aid the Poles.

“I am speaking to you from the Cabinet Room at 10 Downing Street,” Mr. Chamberlain said. “This morning, the British ambassador in Berlin handed the German government an official note stating that unless we heard from them by 11 o’clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received, and consequently, this country is at war with Germany.”

I was not yet 8 years old, but I had been reading the newspapers for some time and discussing the worsening political situation in Europe with my uncle, who lived with us. He was, fortunately, one of those young, elder-brother like uncles who didn’t think it the least bit odd to talk to little girls about matters of world importance. So when the prime minister’s broadcast finished, I knew that without doubt, all our lives were going to change drastically and soon.

First of all, we had to get out of London. Crickle wood, the area in which we lived in the northwest of the capital, was close to a large complex of factories, many of them earmarked for war production. Inevitably, that made them potential targets for bombing by the German Luftwaffe. Our house, barely a quarter-mile away, would just as inevitably become a target too. On the third day of World War II, my father packed his family—my mother, myself, my baby sister and my Uncle Leon—into a large van with as many of our belongings as could be got together in so short a time. Then we set off away from London bound for the countryside. Our destination, Amersham in Buckinghamshire, where my parents had rented a house, was 30 miles away.

In 1939 town children like me often knew little or nothing about the countryside. I had never even seen it. The greatest expanse of greenery I knew was in the local park. Buckinghamshire, which is still a largely rural county, full of farms, fields, woods and acres of rolling country, was a revelation to me. I never realized that flowers could be found any where outside our own front or back gardens, or in the local florist’s shop. But Amersham had entire woods carpeted in bluebells and wildflowers, and there were big haystacks to climb, which enabled me to view vistas of trees, grass and grazing animals that stretched to the horizon. I was understandably entranced by it all. My family and scores of others like us who had fled London seeking rural safety, however, didn’t find it all that easy to fit into this new environment.

‘THEM FOREIGNERS’ AND LOCALS ALIKE HAD TO GET USED TO MANY UNUSUAL SITUATIONS BROUGHT ABOUT BY THE WAR.

The local populace was not all that pleased to see us. In mid-20th-century Britain, town and country folk rarely mixed, much less got to know each other, and townees like us were regarded with suspicion. The locals would speak darkly about “them foreigners up from Lunnon,” or stop talking and watch us with narrowed eyes as we passed by in the street. Even so, “them foreigners” and locals alike had to get used to many unusual situations brought about by the war.

Food rationing was the most fundamental change to everyday life. There were ration coupons for many foods—eggs, butter, meat, fish, sugar and chocolate, for example. Even clothes were rationed. Occasionally, word would go around that a shop was selling oranges, a rare treat in wartime. I used to queue up for our ration at 6 in the morning, but never felt happy about it after I discovered a grim truth. The convoys that brought the oranges to Britain across the Atlantic had to run a gantlet of German submarine and surface-raider attacks. Many of the ships were sunk and many crewmen were killed. It was hard to enjoy eating an orange while thinking about that harsh reality.

Even in Amersham, which was well away from cities likely to be raided by the Luftwaffe, the chance of being bombed had to be taken seriously. We lay along the flight path that led to important industrial centers in central England, like Birmingham and Coventry. One of our precautions was to crisscross windows with sticky tape in case they shattered during an air raid, showering anyone inside a room with knife-sharp pieces of glass. We also had to get used to moving about Amersham at night by shining small torches on the ground to show the way. All the streetlights were out, and traffic lights and car headlights were shielded, revealing only a small cross of light. Blackout curtains covered all the windows of a house during the hours of darkness, so that not even a chink of light could guide enemy bombers flying overhead.

The most important household defense was the air raid shelter installed in every back garden. Ours was made from sheets of corrugated iron, which were sunk about 3 feet down into the earth. Digging out the soil was not a problem; the problem was the water that kept seeping into the hole that we dug. I became quite adept at operating a stirrup pump that removed the water for as long as it took to shore up the sides and get the corrugated iron in place.

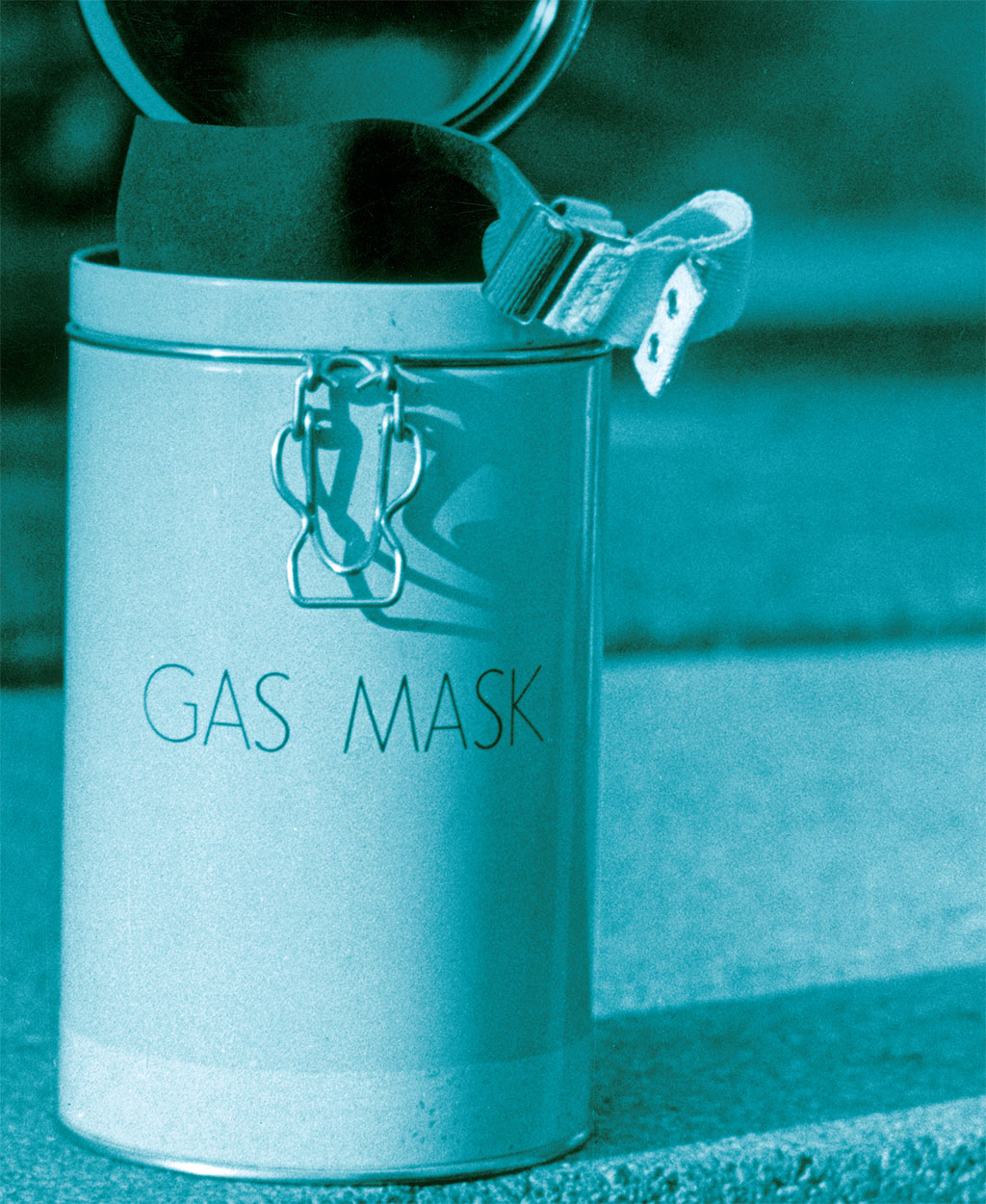

After the raids on British cities began in mid-1940, we started following a regular routine. We left the upstairs bedrooms and instead slept on the ground floor. Each of us had an all-in-one garment known as a “siren suit” that was laid out on the bed before we went to sleep. So was our personal gas mask, which we had to carry at all times in case the Luftwaffe resorted to gas-bombing their targets.

When we heard the air raid siren warning of approaching German aircraft, we got into our siren suits, grabbed our gas masks and went to the French windows at the back of the house. All the lights were off, and in the pitch dark, my parents opened the windows. We ran across the garden and into the air raid shelter, which was lined with mattresses in case we had to sleep there all night. We often did. It is long, long ago now, but the wailing of the air raid siren, usually heard these days on film soundtracks or in television documentaries, never fails to make my heart sink and my stomach contract with fear. I remember, too, the dank, musty smell of the shelter, which, despite my best efforts with the stirrup pump, was never totally dry.

[caption id="ThemForeignersUpfromLunnon_img2" align="aligncenter" width="767"]

COURTESY OF BUCKINGHAMSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL MUSEUM

One night in 1940 while running across the darkened garden to the shelter, I looked up. Outlined in the starlight was a German bomber; I still remember the sinister shine of its fuselage, the identifying black crosses on its wingtips and the throaty roar of its engine.

One of the dangers of being sited along the flight path that Luftwaffe planes took to reach their targets farther north was the chance that they would have to jettison their bombs on the way One or two jettisoned bombs fell on villages around Amersham during the war, and after spending one night in the shelter, my mother noticed a suspicious black cylinder-shaped object lying in our back garden. Fearing that it was an unexploded bomb, she immediately called the air raid wardens and reported the situation. The chief air raid warden was, in fact, the local butcher and very pompous, and he became impatient with her.

“Madam,” the warden told my mother, “can’t you see I’m a busy man? Don’t bother me unless you have a direct hit!”

In 1944 we witnessed what a direct hit could do, when a house on our road became instant rubble and everyone inside was killed. The house was hit by an unmanned flying bomb, one of the Nazis’ so-called “vengeance” weapons, or V-1s, which were fired from sites across the English Channel in German-occupied Europe. The British dubbed the V-1s “doodlebugs,” but they were no laughing matter. The V-1s and their successors, the V-2 rockets, were meant as terror weapons, and they certainly terrified.

I remember hearing one particular V-1 announce its presence over Amersham one afternoon at teatime with the grating, throbbing roar of its engine. Once we heard it, everyone knew what to listen for next: When the engine cut out, it was time to take shelter and pray, for that meant that the flying bomb was about to fall out of the sky. I listened. After a few seconds, the engine cut out. There was a faint rushing sound as the V-1 swept directly overhead. After a moment of silence, a giant explosion rocked our house and shook the teacups off the kitchen table. As the smoke and dust came drifting back along our street, I realized that we had been less than 50 yards away from being killed. I am still unable to hear the sound of a V-1 engine in war films or TV documentaries without catching my breath with trepidation.

[caption id="ThemForeignersUpfromLunnon_img3" align="aligncenter" width="775"]

‘CAN’T YOU SEE I’M A BUSY MAN? DON’T BOTHER ME UNLESS YOU HAVEA DIRECT HIT!’

At the start of 1942, the first American GIs began arriving in Britain. Local people in Amersham were already accustomed to seeing young men in uniform around the town. Nothing, though, prepared Amersham for the Americans. Both literally and metaphorically, they came from another world, with their breezy manners, their informality and, above all, their compulsive pursuit of girls. The “foreigners from Lunnon” were as nothing compared to the difference the GIs made to local life. Girls were romanced as never before by those fresh-faced, brash but charming young men who spared no expense to entertain them. The American PX store resembled an Aladdin’s cave, full of wondrous, never-before-seen goodies like nylons, fine chocolates and chewing gum—all impossible luxuries in tightly rationed wartime Britain. The GIs’ generosity became legendary. They organized parties for the children, piling up a variety of foods that their young guests had never before seen in such quantity.

[caption id="ThemForeignersUpfromLunnon_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

GETTY IMAGES

The GIs never quite got the hang of driving their jeeps on the narrow country roads in and around Amersham. They drove too fast and had to screech to a halt when an unexpected bend appeared in a road or they came across a slow-moving farm cart or a herd of cows. GIs in jeeps gained the reputation of frightening old ladies, but they tended to drive slowly if it gave them the chance to ogle girls walking along the street. Virtually every mother of young girls in Amersham, including mine, kept their daughters well away from the GIs. One day I managed to escape and go to the library. On the way, a couple of GIs pulled up across the road, and gave me my first-ever wolf whistle. By then the gangly almost 8-year-old I had been in 1939 had matured into a well-developed 12-year-old.

Ever since, I have wondered what happened to those two young men and their fellow Americans. With thousands of others they had come to Britain to take part in the invasion of northern France, which took place on D-Day, Tuesday, June 6, 1944. Amersham went very quiet after they left, bound for the most dangerous adventure of their lives. How did “our” GIs fare on the invasion beaches in Normandy and in the long months of fighting that followed? More than 60 years later, many of us still wonder who died and who survived to go home.

We returned to London on July 31, 1945, 12 weeks after the war in Europe came to an end. Two weeks after that, on August 15, I was in the garden when my mother opened a window and shouted, “The Japanese have surrendered!” At last, I thought, at last the war is over! In a sense, though, living through a war meant that it was never entirely over.

In the Buckinghamshire countryside, we escaped the horrifically destructive air raids on British cities, but there was still a peripheral experience whose effect has never faded. It became indelibly printed on my memory, for I can remember my wartime childhood vividly, much of it in mental pictures that remain fresh to this day. The feeling has never dimmed that living through the war, even as a child, meant living through one of the most important and fateful events of the 20th century. It was a worldwide drama played out on the biggest stage, and however young and insignificant I was in the great scheme of things, I had been part of it.

[caption id="ThemForeignersUpfromLunnon_img5" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

GETTY IMAGES

Comments