we are all Albion’s seed: a conversation with David Hackett Fischer

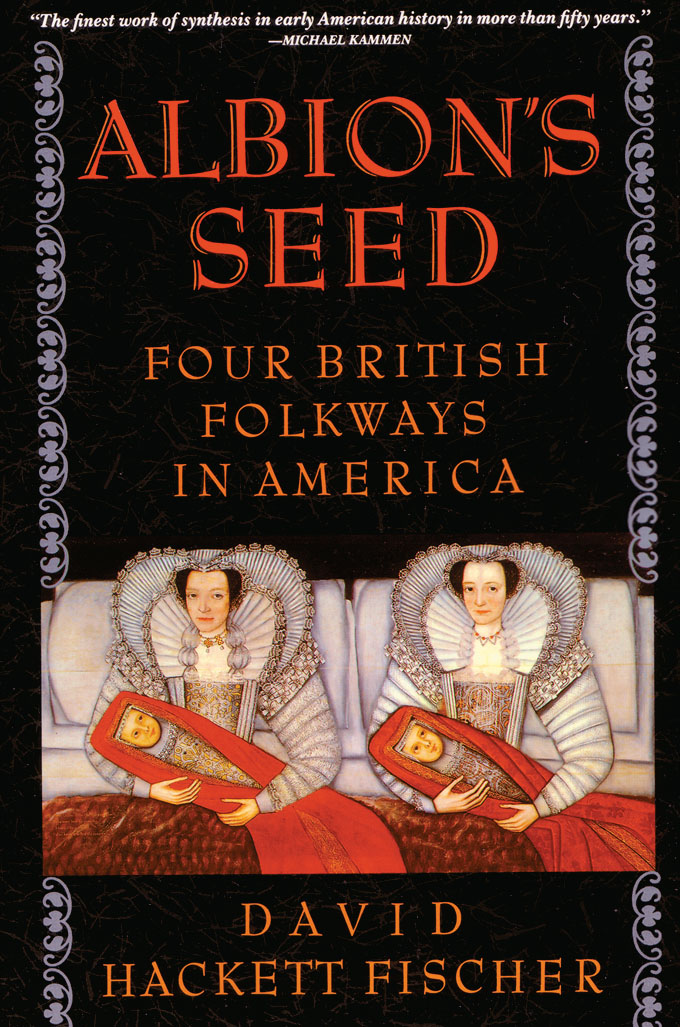

Editor’s note: This issue, British Heritage begins a series of features exploring the four great colonial emigrations into the American colonies during the 17th and 18th centuries. It is from this “betterment migration” out of England, Scotland and Wales that our American culture and regional differences derive. That this is so, and how it is so, is the subject of David Hackett Fischer’s social history Albion’s Seed, widely recognized as one of the most important works in American history in our generation. Professor of history at Brandeis University, Fischer is a prolific writer whose most recent book is Liberty and Freedom: A Visual History of America’s Founding Ideas. I asked George Comtois, recently retired executive director of the Lexington, Massachusetts, Historical Society, to chat with Professor Fischer and provide British Heritage with a general introduction to the new series, “The Great Migrations,” which begins on page 20.

[caption id="Timeline_img1" align="alignright" width="680"]

Courtesy of Oxford University Press

[caption id="Timeline_img2" align="alignright" width="1024"]

HAVE YOU EVER WONDERED what George Washington actually sounded like to his contemporaries? Today we have audio recordings of modern history-mak ers, but will we ever know, even approximately, what Washington and others of his generation sounded like? Thanks to David Hackett Fischer, Brandeis historian and prolific author, the answer is yes—more or less.

In his highly readable history Albion’s Seed, Fischer has provided us with solidly researched and ingeniously integrated answers to this and similar questions, tracing America’s British roots to its 17th- and 18th-century places of origin. The product of this impressive effort is a comprehensive, detailed portrait of colonial America, which accurately explains many American cultural characteristics today.

Fischer analyzed 28 “cultural markers” that make up the building blocks of American society. These include timelinee, religion, family structure, educational content and methodology, social rank, ideology, diet and food preparation, architecture and more.

Why is someone from North Carolina so easily distinguished from a person who grew up in northern Maine? Apart from geography, speech patterns and accents, the two individuals’ tastes in food, styles of cooking and religious preferences are among the noticeable differences. Commercialism and communication have homogenized American society, yet strong regional shadows remain and refuse to be banished by modern technology and new social mores.

According to Fischer, Britain’s earliest immigrants to America came from four geographic regions of Britain: East Anglia, the South and Southwest, the West Midlands, and Wales and Scotland. “Some of the most interesting differences between the four regions in Britain I examined were to be found in people’s ideas about order, power and freedom,” Fischer says.

The Pilgrims who waded ashore at Plymouth Rock and the Puritans who followed them to New England were, for the most part, East Anglians who came from towns such as Boston and Norwich. The Puritan revolution was still two decades away. Many felt that the Church of England had drifted too far from its Christian roots and that God was about to bring the roof of his house down on them. They were being persecuted by the official church, and the New World beckoned with the promise of a fresh start and a safe place to practice their faith.

Tucked away in the Puritans’ cultural baggage were many group behaviors that direct New Englanders’ lives today: a close-knit nuclear family structure and the way they talk, worship, eat, build houses, teach children, govern themselves and celebrate important events, to name a few. These cultural markers to New England society all have exerted a profound influence on how Americans live and on what we now consider “American.”

Indeed the New England “town meeting” is directly descended from Old England, where East Anglian towns in the 17th century exercised considerable local control through the medium of town government—a form of direct democracy. While researching his book in the English parish of Framlingham, Sussex, Fischer found “a musty leather bound folio volume” that contained records of the parish reaching back several centuries before the East Anglian immigration to America. He found that in 14th- and 15th-century England the terms “parish” and “town” were used interchangeably and that the expression “general parish meeting” and “general town meeting” described the same thing. In medieval East Anglia, the “town selectmen” governed the town, just as they do across New England today.

Most broad areas of consensus in American life, Fischer posits, have developed from values derived from its British roots, or as he expresses it, “from values that these four cultures share in common.” For all that, Fischer notes that many of the cultural differences between American regions are greater in some ways than those between European nations. “People in America’s south are more keenly aware of their English heritage than anywhere else in the States,” Fischer says. “This is probably because the proportion of southerners with English ancestry is greater than elsewhere.”

Certainly the “special relationship” that has long existed between the United States and Britain derives ultimately from the colonial roots of our culture. “For obvious reasons, most Americans were distinctly Anglophobic immediately after the Revolution,” Fischer remarks. “However, after 1890 the Anglophiles had definitely overtaken and outnumbered the Anglophobes. This occurred probably because some Americans, made recently wealthy by the Industrial Revolution, wanted the social patina they felt they could garner by identifying with the more venerable English culture.”

A shared history of fighting two hot wars and a cold one through the 20th century has further served to cement an alliance that is as cultural as it is political. “Today, middle-aged and older Britons remain fond of America, left over from World War II. Younger Brits are much less so,” Fischer says. “However, there remain close ties between the two countries with each willing to go to war for the other.”

While the speech of George Washington and his 18th-century Fairfax County, Va., neighbors closely resembled the dialect of England’s southern coast in the 17th century, many of those speech patterns remain alive in Virginia and the Carolinas today.

Ironically, Fischer notes: “English men and women shed their ‘American’ accents late in the 19th century rather than the other way around. This happened because as the Industrial Revolution unfolded, the upper classes in England consciously developed their current mode of speech to distinguish themselves from the ‘working classes.’ So, in truth, it was the British adopting a new way of speaking rather than Americans losing the old.”

BOOK NOTES

Albion’s Seed, by David Hackett Fischer, Oxford University Press, New York, 1989, 946 pages.

Bound Away: Virginia and the Westward Movement, by David Hackett Fischer and James C. Kelly, University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, 2000, 366 pages.

Liberty and Freedom, by David Hackett Fischer, Oxford University Press, 2005, 851 pages.

Comments