John Lilburne and the Levellers

THE GUILDHALL IN LONDON was filled with noisy spectators who had come for the trial of John Lilburne in October 1649. The charge was high treason and the Leveller leader was fighting for his life. The defendant’s supporters outnumbered his opposition by 20-to-1. The court’s judges were mindful of the mood of the crowd and had taken pains to allow Lilburne many liberties. As observed by the judge, Lord Keble, “all that are here are to take notice…that the prisoner…hath had more favour already, then ever any prisoner in England in the like case.” On one point they would not budge, however: They refused him counsel on the technicality that the charge was based on fact and not law. So the agitator used every delaying tactic possible, including calling for a chamber pot.

[caption id="TimelineOctober24261649_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

THE GRANGER COLLECTION,NEW YORK

[caption id="TimelineOctober24261649_img2" align="aligncenter" width="889"]

PRIVATE COLLECTION/BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY

“Sir,” said Lilburne, “if you will be so cruel as not to give me leave to withdraw to ease and refresh my body, I pray you let me do it in the Court. Officer, I entreat you to help me to a chamberpot.” While someone went to fetch the pot, Lilburne took the opportunity to consult law books and notes. When the pot arrived, he used it, then went back to work defending himself.

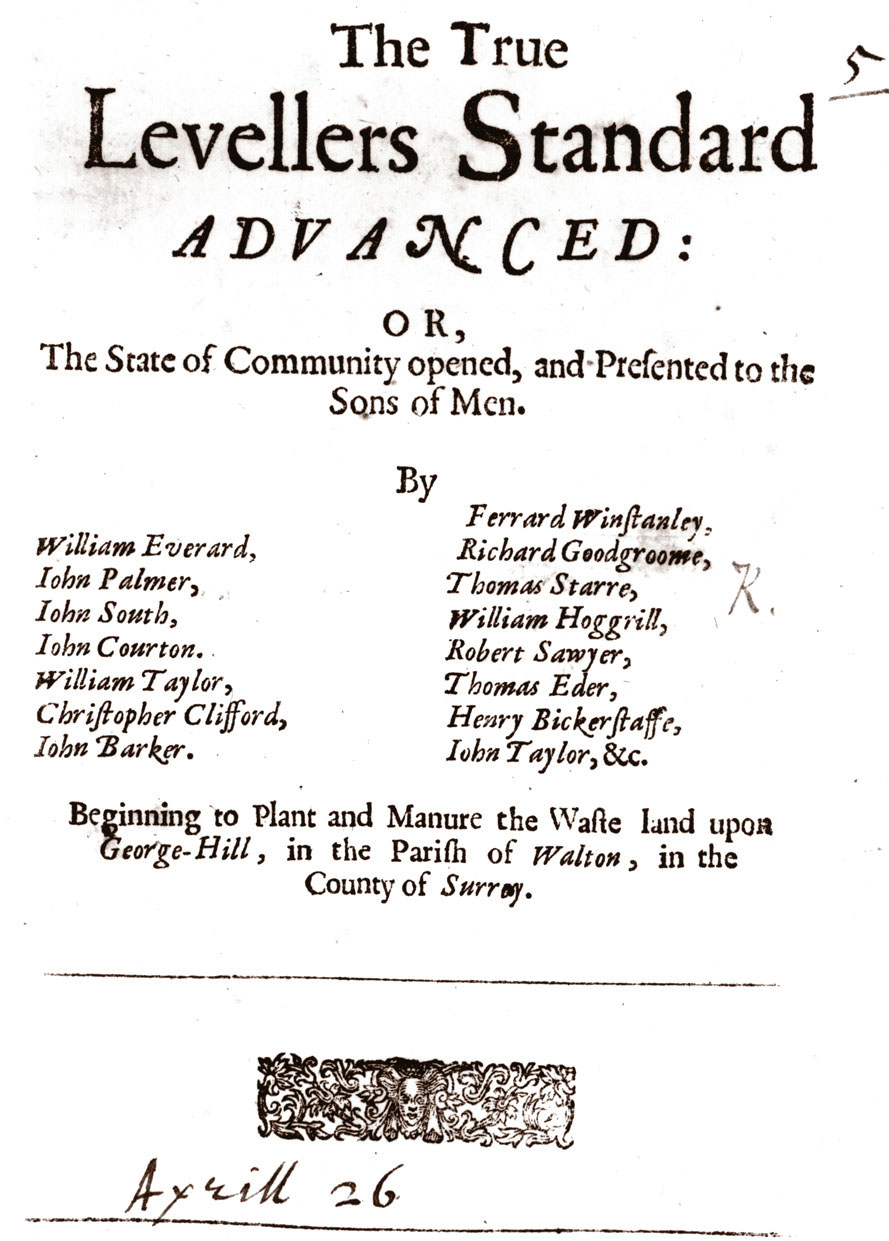

The circumstances that brought John Lilburne to that court at that time were unique in history. England whirled in the cauldron of civil strife. Two years earlier King Charles I had been well on his way to the block, and Parliament reeled in dismay over the power of its own New Model army. Conditions were ripe for the ideas of a small group of innovative thinkers, known as the Levellers, to gain momentum. “By natural birth all men are equal and alike borne to like propriety, liberty and freedom” rang the radical argument made by Richard Overton, a Leveller leader and pamphleteer.

The King James Bible of 1611 had introduced the scripture in the vernacular and initiated a new, never-before-seen and dangerous dialogue on basic human right and religious independence from the state. Leveller literature spread that dialogue, and their manifesto in particular outlined their objectives. The last version, dated May 1, 1649, was penned by Lilburne, Overton, William Walwyn and Thomas Prince from the Tower of London, where they were imprisoned. Titled An Agreement of the Free People of England, Tendered as a Peace-Offering to This Distressed Nation, the document featured 30 provisos that included suffrage for all men (except servants and beggars), regular elections of a representative body, no forced conscription and the end of exemptions from the law because of “Tenure, Grant, Charter, Patent, Degree, or Birth…or privilege of Parliament.”

The treatise also tackled freedom of religion:

[W]e do not impower or entrust our said representatives to continue in force, or to make any Laws, Oaths, or Covenants, whereby to compel by penalties or otherwise any person to any thing in or about matters of faith, Religion or Gods worship or to restrain any person from the profession of his faith, or to exercise of Religion according to his Conscience, nothing having caused more distractions, and heart burnings in all ages, then persecution and molestation for matters of Conscience in and about Religion.

The Leveller cause went beyond elections and religion and tackled the fundamentals of English law. They fought for no self-incrimination, the right to counsel and the right to have “the Laws or proceedings therein” conducted in no “other Languege than English.”

The Levellers argued for “punishments equall to offences: that so mens Lives, Limbs, Liberties, and estates, may not be liable to be taken away upon trivial or slight occasions as they have been.” In addition, the state must allow the benefit of witnesses on the defendant’s behalf “in the case of Tryals for Life, Limb, Liberty, or Estate.”

These forward-thinking men were labeled “levellers” by their enemies, who said their intention was to reduce everyone to the lowest common level. The most prominent Leveller was John Lilburne, and while he and other leaders disagreed with the definition, they kept the name.

Born around 1614, Lilburne came from a prosperous family of the lesser gentry. He moved to London in 1630 to work as an apprentice to a clothier and soon fell in with the Puritan movement. Eight years later the young agitator made his first appearance as a defendant before the Star Chamber.

Lilburne had been caught smuggling tracts against the bishops into England. Brought before the court, he refused to swear the ex officio oath, so as not to incriminate himself or others. As a result he was fined £500, whipped from the Fleet prison to Westminster (a distance of two miles) and pilloried. He was sentenced to remain in prison until he submitted to the court’s authority. That he refused to do. Despite ill health and shackles during his 2½ year stint in prison, Lilburne began his long career as a pamphleteer on behalf of the freeborn rights that belonged to all men.

When the Long Parliament opened, Oliver Cromwell made a petition for Lilburne’s release, and on November 13, 1640, “Free Born” John, as he was called, and other political agitators were released from prison.

When civil war erupted between king and Parliament in 1643, Lilburne joined the Parliamentarian army as a captain and served with distinction. He rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel but resigned from the army in April 1645 because he refused to sign the Solemn League and Covenant, which recognized Presbyterianism as the only legitimate church. From July of that year to February 1649, Lilburne wrote and printed pamphlets, was arrested twice and spent a total of 29 months in prison.

In January 1649, Charles I was executed for treason against the people, and the Council of State assumed control of the government. In the meantime, the agitators found that not much had changed with the death of the monarch and continued printing and distributing pamphlets. Two months after Charles’ death, Lilburne, Walwyn, Overton and Prince were arrested and sent to the Tower for treason.

When he went to trial on October 24, 1649, Lilburne determined not to challenge the authority of the court as he had in the past, but to wear the court down by constantly challenging procedure. One day, after hours of witness testimony followed by Lilburne’s cross-examination, the defendant repeatedly asked for counsel, as matters of law had been introduced. When he was refused, he changed tactics and asked for a recess:

I cannot conceive upon what ground it can be apprehended I can go on, for my time and strength now it is far spent that I conceive you cannot think my body is made of steel, to stand here four or five hours together spending my spirits to answer so many as I have to deal with, and be able after all this, to stand to return an answer to above five hours charge, and that upon life.

When that request too was denied, he asked for the chamber pot.

In the end, the tactics that Lilburne employed in his trial worked, and he was acquitted on October 26, 1649. By that time, however, Cromwell had effectively quashed the Leveller movement. Even so, Lilburne continued to periodically run afoul of the law until his death in 1657.

Lilburne’s legacy was far from over. On June 13, 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court delivered its opinion in the case of Miranda v. Arizona, in which four defendants in police custody had been cut off from the outside world and were questioned without being made aware of their rights. All four defendants confessed and were subsequently convicted.

The Supreme Court ruled that the questioning had violated the defendants’ Fifth Amendment rights and cited Lilburne in its written decision:

We sometimes forget how long it has taken to establish the privilege against self-incrimination…its origins and evolution was the trial of one John Lilburne, a vocal anti-Stuart Leveller. The lofty principles to which Lilburne had appealed during his trial gained popular acceptance in England. These sentiments worked their way over to the Colonies and were implanted after great struggle in the Bill of Rights.

As a consequence of that Supreme Court decision, everyone taken into custody must be notified of their Miranda Rights.

Comments