Best for tombstone tourists: Highgate Cemetery, London.Getty

The countless cemeteries and graveyards across Britain can tell us a great deal about its people and their history.

In this world, nothing can be certain, except death and taxes, or so the quote goes. It means that every community must have a place to bury its dead, and the countless cemeteries and graveyards across Britain can tell us a great deal about its people and their history. They may be the last resting place of the dead but our pick of Britain’s cemeteries are alive with remarkable stories.

Best for royalty: Iona Abbey, Iona

It may be on an isolated isle off the west coast of Scotland, but that hasn’t stopped Iona Abbey being touted as the last resting place of no fewer than 60 monarchs, including kings of Dalriada, Scotland, Ireland and Norway. The royal residents chose the island due to it being a focal point of early Christianity after St Columba founded a monastery there in 563.

The church kept collapsing until Columba had a vision telling him that the church would not be finished until a man was buried below it. Columba’s loyal companion, Oran, volunteered to sacrifice himself for the good of the church and so became the first person buried in the churchyard, named Rèilig Odhrain in his honour.

Among the royal rulers, who joined Oran over subsequent centuries, was Kenneth MacAlpin, the first King of Scotland. Almost 200 years later, one of Shakespeare’s most notorious villains was buried there too, although the real Macbeth is actually considered a fair ruler, who encouraged the spread of Christianity.

Few legible gravestones survive from the early years, but Rèilig Odhrain still accepts new burials and, in 1994, the leader of the Labour Party was buried there. Although he was no royal, had John Smith lived he would have probably become Prime Minister in the 1997 General Election – a landslide that was won by his successor Tony Blair instead.

Best for tombstone tourists: Highgate Cemetery, London

North London is a place of pilgrimage for tombstone tourists looking to tick off another famous grave on their checklist (yes, apparently it is a thing). In the leafy and affluent suburb of Highgate, enjoying marvelous views south over the city, Highgate Cemetery’s 53,000 graves contain the remains of 170,000 individuals among 37 acres of trees, shrubs and wildflowers.

The star of the show is Karl Marx, who found refuge in London after being expelled from Paris, Brussels, and Cologne. His Communist Manifesto proved so influential and divisive in the century after his death that his grave is a Grade I-listed monument and has been the target of two different bombing attempts and several acts of vandalism. If truth be told, that iconic grave is actually Marx’s second. Take an indiscriminate muddy track to find his original resting place among a maze of worn and cracked horizontal gravestones.

There are plenty of other notable residents. Arm yourself with a map or merely wander and stumble across an eclectic selection ranging from Michael Faraday, a scientist who experimented with electricity, to Malcolm McLaren, manager of the Sex Pistols. Leave a pen on the grave of Douglas Adams, one fan left a pen holder on it in case the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy writer wanted to scribble a few posthumous words. George Eliot can also be found here, although you’ll need to look for a headstone bearing the 19th-century author’s real name, Mary Ann Cross.

Best for storytellers: Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh

If proof were needed that dogs really are man’s best friend, you’ll find it at Greyfriars Kirkyard, in the centre of Edinburgh. When nightwatchman John Gray breathed his last in 1858, his Skye terrier, Bobby, spent the next 14 years keeping a lonely vigil by his master’s grave. So charming did the locals find the loyal pooch that they brought him food and, when his own time was up, buried him near his master and erected a statue in his honour.

The story may have been exaggerated – the dog may simply have been a stray who took advantage of a good source of free nosh – but no matter, the legend of Greyfriars Bobby was born and has since inspired a novel and two movies.

Greyfriars is ample proof that cemeteries are a great place for digging up stories. JK Rowling often strolled through the graveyard as she pondered the next plot twist in her Harry Potter novels and will undoubtedly have passed the grave of Thomas Riddell. Was this the subconscious inspiration for Tom Riddle, the boy who would become the arch-villain Lord Voldemort? It hasn’t stopped legions of Potter fans visiting the grave, nor that of William McGonagall, a pulp poet who found cruel fame as one of the worst poets in Scotland. Potterheads think may he have been reborn as Hogwarts’ Professor McGonagall.

Best for history: Eyam Churchyard, Peak District

Three-quarters of the population of Eyam died in 1665 and 1666 – a mortality rate that, although horrendous, was sadly not unusual during the Great Plague. However, the residents of the “plague village” are still remembered due to the courageous 14-month quarantine that their vicar, William Mompesson, persuaded them to adopt. Though his actions may have increased the death toll in Eyam itself, it prevented more deaths by stopping the disease spreading to neighboring areas.

There are few plague burials in the graveyard of St Lawrence’s Church since families were expected to dispose of their own dead during the outbreak, but one victim was granted a grave topped by a large stone sarcophagus, near the church door. This is the last resting place of Catherine Mompesson, wife of William, who caught the plague and died in the final weeks of the epidemic – one of the last to expire before her husband’s quarantine came to an end.

This pretty Peak District churchyard is also notable for a carved Saxon standing cross dating to the 8th century – it was probably a preaching cross marking where services took place before the church was built – and an 18th-century sundial above the church door. However, it will always be known as the focal point of a self-imposed village of the damned.

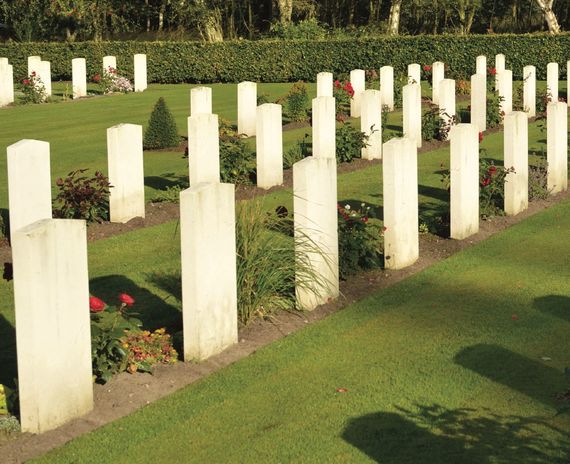

Best for war graves: Cannock Chase War Cemeteries, Staffordshire

Commonwealth War Graves.

The countryside of Cannock Chase is a popular spot for walkers and mountain bikers, but more than a century ago its open land made it an ideal place for First World War training and prisoner internment camps. Poignant evidence of Chase’s wartime past can still be found at the edge of Camp Road: neat rows of white marble headstones surrounded by perfectly manicured grass. Some of the burials in Cannock Chase War Cemetery contain the bodies of a number of New Zealanders who died in the final days of the war after contracting the dreaded Spanish flu but the majority of the 379 internments are German prisoners who were captured and never made it home.

Follow the lane away from the road to discover a second military cemetery, this one under the aegis of the German War Graves Commission. In the 1960s, any German soldiers from the First or Second World Wars not buried in a British war cemetery, were exhumed and reburied together on a site put aside for them on Cannock Chase.

The contrast with the neighboring Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery is striking. The German cemetery feels isolated, surrounded by woodland and away from the road, with the graves sloping down the sides of a natural grass bowl. The grey headstones mark the last resting place of up to four soldiers, two names on the front, two on the back, meaning that nearly 5,000 servicemen are squeezed in to this eerily quiet corner of a foreign field.

Best for ghosts: St Mary’s Churchyard, Whitby

You’ll be forgiven if the hairs on the back of your neck stand up after climbing the 199 steps to the cliff-top church of St Mary’s. Located next to atmospheric Whitby Abbey, whose ruins alone make the uphill trek worthwhile St Mary’s found fame at the end of the 19th century when Bram Stoker used its graveyard as a location in Dracula.

The author was holidaying in the seaside town when he found references to a 15th-century Transylvanian prince with a fondness for torture. Add in a great deal of inspiration from his surroundings and an iconic villain was born.

Fanciful storytellers will point to two nameless gravestones bearing carvings of skulls and crossbones and claim that pirates are buried beneath them, but the simple explanation is that the skull-and-crossbones motif was commonly used on the gravestones of freemasons. There are, however, plenty of seafaring burials as would be expected in a once-thriving port. Among them is William Scoresby, Arctic whaler and inventor of the crow’s nest.

Keep an eye out for graves with nobody interred – look for the phrases “in remembrance of” and “in memory of” on the headstones. These were unfortunate mariners whose ships and crews were lost at sea and whose funerals took place with no body. Either that or Dracula has carried them off.

Best for wildlife: Nunhead Cemetery, London

Best for wildlife: Nunhead Cemetery, London.

The population explosion in London in the first decades of the 19th century meant that parish graveyards were soon overrun with new occupants. The government’s response was the creation of the Magnificent Seven, a series of new private cemeteries surrounding the capital with the ability to cope with the growing population. Highgate Cemetery may be the most famous but do not overlook the others, particularly the hidden gem that is Nunhead, in Southwark.

Originally known as All Saints’ Cemetery, Nunhead was closed to new burials in the 1960s and effectively abandoned by its owners. Although it is now cared for by a dedicated team of volunteers, the years of neglect allowed nature to reclaim the 52-acre site. The result is a nature reserve where wildlife thrives among the dead. Vines grow over paths and graves, birds sing from the tree branches and countless insects live in the undergrowth. Foxes and badgers live here too, although you’ll need to visit early or late to have a chance of glimpsing them. Get lost in the maze of paths and enjoy the wildlife that has made a home alongside London’s past residents.

Climb a hill on the western side for an excellent view down to the city and St Paul’s Cathedral. The cemetery’s own place of worship, a Gothic-style chapel, was sadly destroyed in an arson attack in 1976, but the ruins have been stabilized and are now used for music and theatre performances. New life is returning to a once forgotten burial ground.

Comments