Where Little England meets the Celts in Pembrokeshire

[caption id="UptheWelshandDownBelow_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

©JON ARNOLD IMAGES LTD/ALAMY

Sooner or later on a trip to Pembrokeshire you hear someone speak of the “Down Belowers” when referring to people in the south of the county; or “Up the Welsh” when referring to those in the north. The phrase “Little England Beyond Wales” surely pops up, too. With the Second Severn Crossing into England a fair 90 minutes’ drive away, and London getting on for another two hours, you might wonder what “England” is meant.

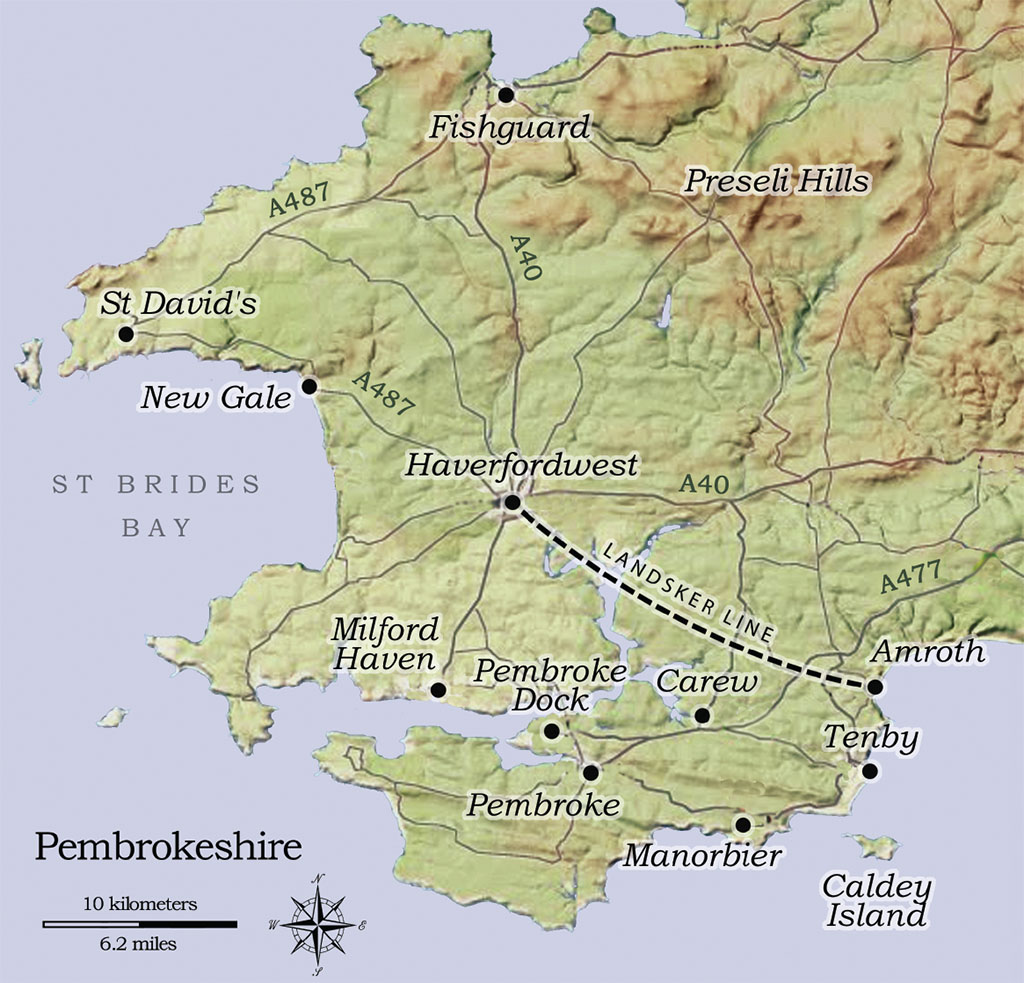

The conundrum is explained by the historic linguistic divide known as the Landsker Line. When the Normans invaded south Pembrokeshire in the 11th century, they built a string of castles to guard their lands, and a frontier developed: Welsh language and culture prevailed to the north, while in the south life became Anglicised, hence Little England. At one time, Flemish immigrants created a sort of buffer zone between the two.

The Landsker Line (the name possibly comes from the Norse for frontier) stretches across Pembrokeshire roughly from Newgale on St. Brides Bay in the west to Amroth on Carmarthen Bay in the southeast. Star-crossed lovers who marry across the divide may no longer be ostracized, but there’s still a different sense of identity: Traditionally Nonconformist to the north and Anglican/Catholic communities to the south.

The scattered villages of the Welsh-speaking areas also generally have starker architecture, while the Down Belowers talk with quasi-West of England accents and have a heritage of dialect words: Longdogs to describe an athletic person, for example. It’s amazing that, unsupported by any law or border patrol, such a curious regional split has survived.

[caption id="UptheWelshandDownBelow_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

GREGIRY PROCH

’STAR—CROSSED LOVERS MAY NOT BE OSTRACIZED, BUTTHERE’S A DIFFERENT IDENTITY’

[caption id="UptheWelshandDownBelow_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

©LOOP IMAGES/ROY SHAKESPEARE

You could devote a whole trip to visiting Pembrokeshire’s castles and strongholds—there are over 50. Come in on the A40 road via Whitland, more or less following the line of the Landsker borderlands: Just to the north there’s 12th-century Llawhaden, which grew into a bishop’s palace, and motte-and-bailey Wiston in the village of that name. But some of the best sites are deep in Little England—near neighbors Pembroke, Manorbier and Carew are top of my list and can be “done” in a day, if you don’t get distracted.

Pembroke Castle, surging above the River Cleddau, is a massive, loud and proud piece of medieval masonry on Norman foundations. There’s a good exhibition highlighting its history—sieges by the Welsh, and by both Roundheads and Cavaliers in the English Civil War. Not least, Henry Tudor, later Henry VII, was born here in 1457. But it’s the thumping impression of the stonework that lingers longest: The 12th-century, 75-80-foot circular keep with “I’m-king-of-the-castle” views from the top, the great gatehouse and tunnels and stairways that conjure up footsteps from the past.

My second stop, just five miles northeast, is Carew Castle, equally picturesque beside a tidal creek of the Daugleddau (Welsh for “two swords”) estuary. The architectural interest here is how Norman earth and timber morphed via medieval fortress into an Elizabethan country house; there’s a superb Celtic Cross and fully restored 18th-century tidal mill, too. Romance, rough and tumble are delivered in the 12th-century story of the Anglo-Norman baron Gerald de Windsor and Owain ap Cadwgan, who tussled over Princess Nest, the troublesomely “most beautiful woman in Wales.”

Press on, then, to the south coast where the battlemented curtain wall of Manorbier Castle is firmly planted amid fields sloping down to a sandy cove. It always strikes me as incongruous to find such mighty piles in otherwise quiet village locations—but that’s just how it was. You can imagine the bristling sense of power over the peasants that came with such an abode.

Land at Manorbier was given to Odo de Barri, a Norman knight who helped to conquer Pembrokeshire. His fourth son was Gerald of Wales, 12th-century scholar, traveler and chronicler of contemporary life. Without a hint of favoritism, Gerald wrote of his hometown: “Heaven’s breath smells so wooingly…. In all the broad lands of Wales, Manorbier is the most pleasant place by far.”

After you have a scamper about the great hall, turrets and chapel, scarcely altered since the Middle Ages, the Castle Inn beckons with generous refreshment.

There is, of course, far more to Pembrokeshire than its castles. Ocean besieges this crooked elbow of a county on three sides along 185 miles or so of rugged coastline, sculpting sandy resorts and watersports heaven. You can walk the whole Coastal Path in 15 days, if you’re inclined. Historically, copper and culture were transported west across the Irish Sea, while saints and pilgrims plied back and forth on coracles. Today farming and tourism prevail.

The landscape can be wildly beautiful—two thirds of the region is designated National Park—and to the west and north around St. David’s and the Preseli Hills there’s a real sense of mystery in ancient stones and legends. Gorse-strewn fields and slightly old-fashioned settlements call to mind Cornwall, only less visited.

Three touring bases highlight distinct facets of Pembrokeshire’s attraction: Tenby on the south coast, St. David’s to the west, and Fishguard, gateway to the Bluestone Country in the north.

Take the picture-postcard view of Tenby from the clifftop, with its pastel-colored Georgian houses sprucely lining the sandy North Beach and harbor; you could be in Devon. Little England? You bet.

[caption id="UptheWelshandDownBelow_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

©PAUL FELIX PHOTOGRAPHY/ALAMY

Norman invaders established the original fortified town, and the Welsh called it Dinbych y Pysgod, Little Fort of the Fish, which tells its own story. Most of the medieval town walls remain, but only a small keep tower of Tenby Castle survives on the breezy beachside hill. It’s put to good use housing a museum of local life and an art gallery that features changing displays.

There are also pleasantly labyrinthine, cobbled streets to explore: The must see is the 15th-century, three-story Tudor Merchant’s House on Quay Hill, whose rooms evoke the life of prosperous mercantile inhabitants when Tenby was a busy trading port.

For an unusual (summer-only) excursion, escape to Caldey Island, a 20-minute boat ride away. Monks first lived on 550-acre Caldey 1,500 years ago, and it’s now owned by Reformed Cistercians. Rattle up to the village on a tractor-drawn trailer where the Italianate abbey beams down on whitewashed cottages, a post office, souvenir shop, tea garden and churches.

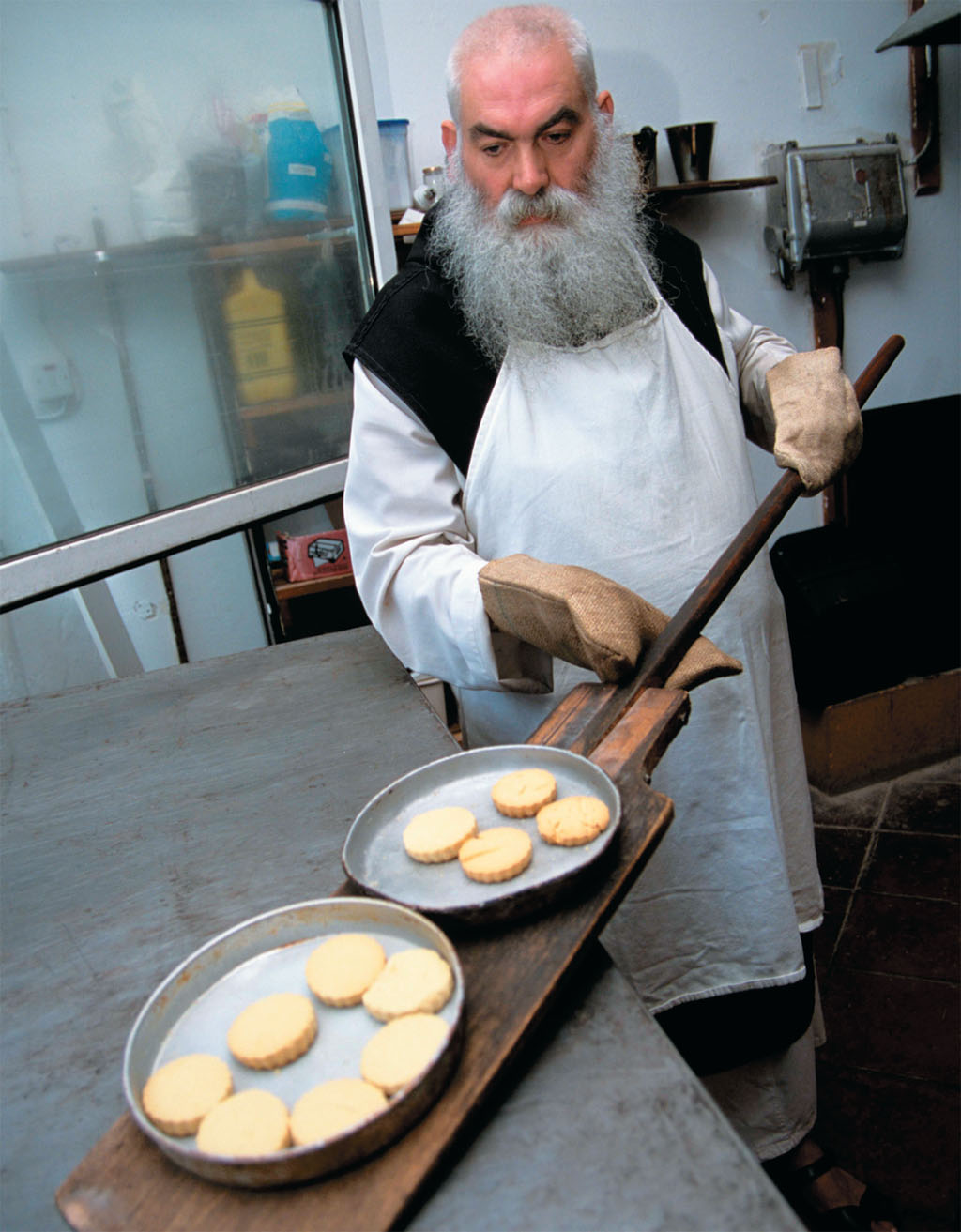

The monks are a quiet bunch, but friendly. Brother Gildas (“I’m the front man”) showed me around. White bearded and twinkleeyed, if he wasn’t a monk, he’d be Father Christmas. The small community aims to be self-sufficient through farming and making shortbread, chocolates and perfumes with dare-to-try fragrances such as Island Gorse (www.caldey-island.co.uk). They also celebrate seven prayer services a day, beginning at 3:30 in the morning.

“Living here is very different from modern urban society,” Brother Gildas told me in classic understatement.

From Tenby, take your pick of routes up to St. David’s. You could zig-zag through Manorbier, Pembroke and Carew before joining the A40. Pembroke, in particular, is worth more than a look at the castle. An erstwhile medieval fortified town, its ancient walls and a few defensive towers pass muster, and the main street with its old buildings, cafes and shops has chintzy appeal.

Alternatively, make your way via Narberth, straddling the Landsker Line and quite a trendy little arts and crafts place. Then it’s along the A40 to the county town of Haverfordwest. At Newgale, you join some of the most eye-catching stretches of coast, along the yawn of St. Brides Bay. Then you’re plunged through places with names like Pen y Cwm, clearly Up the Welsh territory now. Soon St. David’s hoves into view.

The stone-and-pastel cottages and tea shops of St. David’s are undeniably the stuff of tourists’ dreams. With a population of less than 2,000, it’s Britain’s smallest city and, but for its 12th-century cathedral, would be a village. Wales’ patron saint, David, founded a settlement on the spot in the 6th century, and pilgrims have come here since the Middle Ages. The sudden vision of the purple sandstone edifice, literally down a village lane, is breathtaking.

Inside the cathedral, along with the alleged relics of St. David, there are some fascinating tombs, treasures and painted ceilings. I love the 16th-century humor of the misericords in the choir, showing boat builders with backache and seasick pilgrims voyaging from Ireland. In the refectory, over tea and cakes, I was also tickled to note a sign proclaiming it’s a wi-fi hotspot: You’d expect nothing less than the clearest of communications through the ether here!

Away from the cathedral and ruined 14th-century Bishop’s Palace, on the grassy cliffs, you’ll find St. Non’s Well and the site where she is said to have given birth to St. David. This blustery, luminous spot reverberates with natural spiritual atmosphere, where spring sea pinks, violets, sea campioin and bluebells flourish.

Back in the car, it’s on along grass-banked lanes, via hilltop settlements like Mathry (and the Farmers Arms pub), to Fishguard. The town divides into three: the upper/main town, the picturesque lower town of pastelshaded cottages around the harbor and Goodwick, where the ferry port does a good trade with Ireland.

The Town Hall is home to the Tourist Information Centre and also the Last Invasion Tapestry: A humorous, Bayeux-style work depicting events of 1797 when a motley bunch of Frenchmen arrived at Carreg Wastad, near Fishguard. They were captured after a few drink-fuelled hours by, among others, a pitchfork-wielding local heroine named Jemima Nicholas. The last invasion of Britain was thwarted. The Royal Oak on the Square, a typical pub, boasts the very table on which the peace treaty was signed!

Follow the Marine Walk from the main town, and you can browse information panels on Fishguard’s busy past as a herring port, and its role in the Rebecca Riots against turnpike tolls in the 1840s.

‘THE NATURAL THEATER OF MOUNTAIN, WOODS AND WIDE, BLUE SKIES IS TREMENDOUS’

[caption id="UptheWelshandDownBelow_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

© LOOP IMAGES/ROY SHAKESPEARE

Potted Pembrokeshire

General info: Can be found at www.visitpembrokeshire.co.uk

Getting there: The county is best explored by car. However, trains run to Fishguard, Haverfordwest and Milford Haven in northern Pembrokeshire, and to Tenby, Pembroke and Pembroke Dock in the south www.nationalrail.co.uk

Staying: Bay House, Tenby www.bayhousetenby.co.uk Five-star Victorian townhouse B&B, £35-£40 per person

Manor Town House, Fishguard www.manortownhouse.com Four-star Georgian town house, B&B £37.50-£42.50

Warpool Court Hotel, St. Davids www.warpoolcourthotel.com Three-star Victorian country house hotel, B&B £90-£150

Eating out: Cwtch, St. Davids, tel: 01437 720491, www.cwtchrestaurant.co.uk

Freshwater Inn, Freshwater East, Pembroke, tel: 01646 672828

Llys Meddyg, Newport, near Fishguard, tel: 01239 820008, www.llysmeddyg.com

Festivals: You’re never more than 12 miles from the sea in Pembrokeshire, so little wonder the county celebrates its seafood and fishing heritage with a Fish Week, www.pembrokeshirefishweek.co.uk. Look out for gourmet seafood evenings, fresh mackerel barbecues at the county’s harbors, lobster lunch teamed with river trips, and 200 or so other events. Dates for 2010 are June 26-July 4.

For more seasonal events, see www.eventsinpembrokeshire.com

[caption id="UptheWelshandDownBelow_img5" align="aligncenter" width="933"]

© LOOP IMAGES/CHRIS WARREN

There was further riotous behavior in the town in 1972 when Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor and Peter O’Toole descended to film Dylan Thomas’ Under Milk Wood, the harbor starring as the town of Llareggub. It seems Taylor was rather piqued that her husband preferred late-night drinking with O’Toole and locals in The Ship Inn to her company back at the hotel.

[caption id="UptheWelshandDownBelow_img6" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

© JOAN GRAVELL/ALAMY

I was told this by local Shirley Matthews, whose former policeman husband was charged with guarding Taylor. This summer I went with Shirley and her pal Mary Baker for an escapade into Bluestone Country, where the Preseli Hills are said to mark the entrance to the Celtic Underworld. Mary is an archaeology buff and likes to share her passion with visitors (www.archaeotours.co.uk).

So, we took the road out from Fishguard and into the lovely-wild Gwaun Valley. The Preseli Hills abound with Neolithic burial chambers, Bronze Age cairns, standing stones and Iron Age forts. And, of course, they are the source of the famous spotted dolerite or bluestones that ended up at Stonehenge in Wiltshire.

“I think there was something particularly powerful about the west of Wales, the land of the dying sun, that attracted people,” Mary suggests. You can certainly picture all those early folk watching hopefully for the new day rising above the mountain ridges.

If nothing else, view the cromlech of Carreg Samson, near Abercastle—St. Samson allegedly balanced the capstone in place using only his little finger. And wander around the hefty bluestone slabs of the Pentre Ifan burial chamber near Nevern, handiwork dating back to 3500 BC. The natural theater of mountain, woodland and wide, blue skies is tremendous.

We picnicked at the village of Nevern, where the inevitable ruins of yet another Norman castle are surpassed by the Church of St. Brynach on the pilgrims’ route to St. David’s. In the woods above the church, you can see medieval pilgrims’ footsteps worn into the rock. Rare bilingual monuments in the 6th-century-origin church have helped scholars unlock the Ogham alphabet, and in the churchyard there’s a superb 10th-century Celtic cross.

“This was a really buzzing, pioneering place for early Christianity, with exchanges of knowledge with Ireland,” Mary says.

As we dropped back down from Up the Welsh via Crymych, it did seem that we had been in another world. Mary feels that modern-day widespread teaching of Welsh in schools is weakening the divide with Little England, yet the Landsker Line nevertheless remains quite clear-cut. It certainly gives to the region a unique dynamic and character, and whether you go Up the Welsh or Down Below it’s an intriguing, dramatic place to tour.

Comments