The theory is that a member of Parliament should not do just one job

Last issue, British Heritage readers met MP Patrick Mercer (C) from Newark. Unusually in the British parliamentary system of government, Mercer represents the constituency in Nottinghamshire that is his home. It was also the constituency of the great 19th-century Liberal statesman William Gladstone. It’s a long way from the heart-of-England market town at the crossroads to the corridors of power in Westminster.

I visited with MP Mercer in his office at Portcullis House, just across the street from the Houses of Parliament, on the corner of Westminster Bridge next to the statue of Queen Boadicea. What is an MP’s working life in Parliament? How do you tend your constituency? What are the rhythms of the political year? Inquiring British Heritage readers want to know. In the corner of his functional and slightly rumpled office, Mercer lounged comfortably in his overstuffed contemporary reading chair and affably talked of his work.

The Parliamentary year roughly follows the school year. There are long recesses for Christmas and Easter and a summer adjournment that runs from late July to the first of October. Parliament is in session for about eight months of the year.

During the parliament session, the house sits Monday to Thursday. On Thursday night, Patrick Mercer catches a train home to his constituency in Newark. The long weekend is spent tending to constituency business and attending official and unofficial local meetings and events. He returns by train to Westminster on Monday morning.

“During recesses, it’s up to me how much time I spend in my constituency. The fact remains that I live in my constituency, which is quite unusual,” Mercer explains. Because a party’s candidates are selected by party committee rather than by local primaries, there is no tradition of local candidates representing local constituencies.

For Mercer, however, that local connection is important. “That’s the pleasure for me in what I do. I don’t want to represent anywhere other than where I do live. All my roots are local, and I have great pride in representing the people of Newark. They see me in daily life—as someone like them who just happens to represent them in Parliament. That’s important to me.”

Generally, the Commons is called into session for the day at 2:30 in the afternoon. It subsequently engages in deliberation, debating and the process of voting until adjournment often after midnight. Odd as that daily schedule might appear, there is method in the clockworks. After all, being an MP is just a part-time job.

American congressmen are strictly governed over their “outside interests” and sources of income beyond their congressional salaries. And we certainly expect a full day’s work out of our legislators. Britain’s parliament evolved over centuries in a very different way from our own governing institutions, however. They look at it quite differently.

“The theory is that a member of Parliament should not do just one job,” Mercer explains, “—that he or she have some other form of employment or remuneration so they can continue leading a commercial life while they are a member of parliament.”

Members of Parliament are expected to have outside interests—independent businesses, company directorships, editing or writing contracts, consultancies. Or jobs in various ministerial positions within the Government. The Commons does not convene in the mornings, however, to allow members to attend to their “outside interests.”

“In practice, though, I’m in my office just after 9; I’ve got to have access to my staff and to people who work regular 9-5 days,” said Mercer. When the House is in session, deliberation and debate govern the Commons. It’s never expected that all members be present during the discussions; there aren’t enough seats for them all at the same time in the house. From a CCTV mounted in his office, Mercer can work while keeping a weather-cocked eye on the action taking place on the floor across the street.

While we are chatting, Big Ben and his friends, just yards away, interrupted us ringing the Westminster Chimes.

“It varies, but generally we start voting at about 8 in the evening. The voting process usually takes through to the small hours of the following morning. Actually, time can weigh very heavy on your hands in the evening hours when you’re waiting to vote,” confesses Mercer.

Life seems a little simpler in Parliament than in Congress. Mercer’s staff totals just two and a part-timer. He has a crack personal assistant in the outer office of his two-room office suite. Another valued aide maintains his constituency office back in Newark. A part-time assistant works on legislative or constituency issues. MPs may choose to take work on parliamentary committees that customarily meet on Tuesday and Thursday mornings. Though Mercer has chaired the Homeland Security subcommittee, he doesn’t presently serve on a committee.

The division bell rings; MP Mercer is summoned across the street to vote. “Just sit tight; I’ll be back in a few minutes.” I picked up a magazine and read an article Mercer had written on military history. Among Mercer’s own outside interests, he also writes historical novels, most recently Red Runs the Helmand.

On his return from the vote, Mercer suggested we continue chatting over dinner. The Commons had adjourned early tonight. We crossed under Bridge Street into Westminster Palace. Colleagues brushed by and Mercer was stopped several times for brief exchanges as MPs headed to their offices and then out into a rare Wednesday evening away from the house.

The member’s dining room in the Commons is suitably impressive, with ceilings rising to infinity, dark oak and ornate plasterwork. We have a table by the arching window, overlooking the River Thames. All is white linen and silver service. Dinner is as sumptuous as the surroundings.

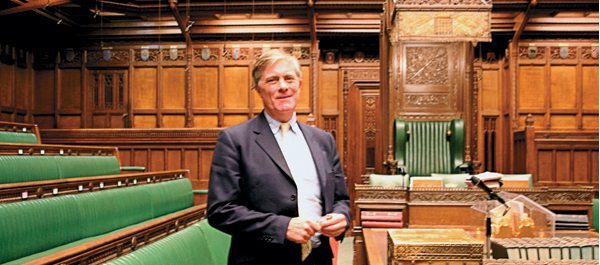

After coffee and a bit of English cheese, Mercer led me through the central rotunda, rich with gilding and mosaics. We surreptitiously captured him next to Gladstone’s statue, and turned out onto the floor of the Commons. The chamber was empty, yet fully lit; the galleries and back benches, so full of history, rose in tiers on either side and those famous lines two sword-lengths apart indicated that they must have had pretty long swords in the old days. We stood chatting by the desk from which so many great PMs have customarily addressed the House.

I shook my head. “Patrick, you probably take all this for granted after a while,” I said, “but you work in some pretty fabulous surroundings.”

Mercer chuckled, “Yes, it does become just the office.”

He offered to let me out the front door. It was quiet, dark and foggy as the massive door swung open facing an empty Parliament Square. “I’ll take your visitor badge back to security,” Mercer volunteered.

Comments