EXHIBITION

The Last Debutantes, Kensington Palace The Last Debutantes exhibition runs daily at Kensington Palace until June 14. Entry is included in the Kensington Palace admission charges. Adult £12.30, child £6.15. There are reductions if prebooking online at www.hrp.org.uk.

KENSINGTON PALACE is a perfect venue for “The Last Debutantes,” an exhibition about the dizzy, champagne-fueled world of the Debs, their Delights—and their demise. The palace’s faded grandeur and dusty royalty fits, as snugly as a Balmain dress, a time and place where sequins and satin, tiaras and veils signaled a young aristocrat’s launch into society. A launch where the high life, fast cars and a dazzling whirl of engagements came with a rock-solid list of caveats and rules as strict as her chaperone. In one spectacular season, prescribed by years of tradition, the privileged 18-year-old would attend everything from Ascot to the Chelsea Flower Show, and be expected to both throw and attend parties to remember.

The exhibition (which is really an excuse to show off some of the extraordinary confections of dresses by the big-hitter designers of the day—Worth, Dior, Heim) also touches on the other aspects of “Coming Out”—in the old-fashioned sense. The history of the Season, regulations, presentation at court (including a few embarrassing stories from debs who toppled over while trying to curtsey to Her Majesty)—and of course, the men, who ranged from gauche young clodhoppers to sleazy old lounge-lizards. The deb’s foremost job was to negotiate these two extremes and find a husband from a “suitable background.”

In one room a bank of TV screens shows interviews with the very last “Debs”—and their consorts, the “Debs’ Delights.” Now in their 70s, they remember their first seasons as though it were yesterday, and their reminiscences are artfully juxtaposed with memories from people who didn’t form part of this tiny elite—and the way they celebrated being teenagers. The last season when debutantes were formally presented at court, 1958 was also a year of social unrest and political activism, and the exhibition is careful to cover both. World War II, the slow decline of the British Empire—not to mention Cliff Richard, dansettes and Teddy boys—had made dinosaurs of the debs in the Brave New World of postwar Britain.

[caption id="WhenYoungLadiesWerePresentedatCourt_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

RICHARD LEA-HAIR/NEWS TEAM INTERNATIONAL

But it’s the dresses themselves that are the stars of this particular show. The demure white dresses in which the terrified young girls were paraded before the court and presented to the monarch of the day, the obligatory veil by now a mere white fountain of filmy froth nestled into glossily brushed bob cuts. The afternoon tea dresses, in floaty florals and pastel shades complete with matching win-klepicker stilettos and omnipresent wristlength gloves, just itching to slip back into the heady round of champagne, strawberries and tiffin when Britain still (just about) ruled the waves. The often rather daring—but always exquisite—gowns, carefully preserved in oceans of tissue paper, allowed a few precious months of being admired once more; their minute wasp-waists and billowing chiffon skirts puffed with petticoats, their squeezed and padded bodices held up merely by a combination of jewel-crusted whalebone and willpower. Male visitors may choose to sit this one out. There’s a lovely tearoom in the Orangery.

—Sandra Lawrence

DVD

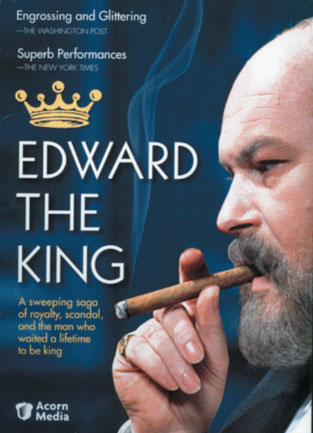

Edward the King, 4-vol. boxed set, Acorn Media, Silver Spring, Md., 13 episodes, app. 650 minutes, $59.95.

[caption id="WhenYoungLadiesWerePresentedatCourt_img2" align="alignright" width="313"]

PERHAPS NO MONARCH in British history was as much a product of his times and his environment as was King Edward VII. Both cosseted and driven by his parents as a boy, as an adult, Bertie—as he was universally called—was kept largely indolent and frustrated by his mother Queen Victoria’s absolute refusal to allow him anything constructive to do with his privileged life.

So Bertie had 40 years to become corpulent, petulant, self-indulgent—and charming. By the time the prince came to the throne on his mother’s death in 1901, he was already at retirement age. Like Shakespeare’s Prince Hal, however, Bertie rose to the occasion as King Edward VII and proved a skilled and successful diplomat, respected across Europe and loved across the Empire.

Acorn Media has found another gem from the past and brought it to general availability for the first time. First broadcast in 1975, Edward the King won multiple BAFTAS, including best drama series, and an Emmy. The series stands the test of time brilliantly and deserves fresh acclaim.

Timothy West does a superb job depicting the Prince of Wales, oldest son of Victoria and Albert. He is surrounded by a great all-star ensemble cast, but the story and the screen are his. Fans of British drama will much enjoy catching early appearances of later stars. A young Felicity Kendal plays Princess Vickie, married into the Prussian royal family and mother of Kaiser Wilhelm. Robert Hardy plays Prince Albert brilliantly and Sir John Gielgud, unlikely as the casting seems, is a most credible Benjamin Disraeli.

With 13 episodes, this story of Edward’s life and times is no miniseries. From his birth and childhood at Osborne House to the nine years Bertie spent as king, we are a silent witness to the great events and people of his time: Prime ministers come and go, siblings grow and intermarry with Europe’s royal families, friends age and friendships sadly change and shadows fall across the Empire that will become the darkness of World War I.

Britain was riding high when Edward VII took the crown. The British Empire was at its apogee and the British navy did indeed rule the waves. Edward VII gave his name to a brief era when the nation crested in its self-confidence and conspicuous wealth. As king, Edward became an appropriate emblem of the time. This sweeping saga brings both the Victorian and Edwardian ages to life in historical drama at its finest.

BOOK

Florence Nightingale: The Making of an Icon, by Mark Bostridge, Farrar Straus Giroux, New York, 600 pages, hardcover, $35.

[caption id="WhenYoungLadiesWerePresentedatCourt_img3" align="alignright" width="260"]

THE “LADY WITH THE LAMP” is the icon—patrolling the military hospital corridors and wards in the Crimea deep into the night. It was there in the mid-1850s that Florence Nightingale earned her veneer of sainthood and her fame. Recognized as the virtual mother of modern nursing, Nightingale introduced many of the principles of sound nursing care and sanitation into common use and elevated the quality, education, status and professionalism of nursing.

The woman behind the icon was more complex, as Mark Bostridge compellingly writes. In what is being described as the first major biography of Florence Nightingale in more than 50 years, Bostridge unwraps the many frustrated layers of Nightingale, her accomplishments and the myths that grew up around her. What emerges is the icon, which she largely made of herself.

[caption id="WhenYoungLadiesWerePresentedatCourt_img4" align="aligncenter" width="676"]

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

From 1854 to 1856, when she was in her mid-30s, Florence Nightingale attended wounded and dying British soldiers at the Barrack Hospital in Scutari, Turkey. They were the only genuinely active years of her professional life. From her teen years, she felt strongly a spiritual, almost mystical, call of God to do something significant and meaningful with her life. She seems to have taken greatest happiness and solace from nursing and caring for the sick and infirm. Into her 30s, however, she was constrained to the acceptable domestic life of her affluent and social-climbing family.

Nightingale escaped her family and made her famous mark during the Crimean War. For the next half-century, she capitalized on her celebrity and used it with some ruthlessness for championing a variety of social causes, from organizing a sewage system for India to the establishment of the Nightingale School of Nursing at St. Thomas’ Hospital. Remarkably, most of her post-Crimean accomplishments were directed from her own sickbed. She spent most of her last decades as an invalid with what is now considered to have been brucellosis.

What emerges from Bostridge’s portrait of Florence Nightingale is not a woman whose accomplishments or aptitude lay in nursing, but as a world-class organizer, administrator, number-cruncher and, yes, self-promoter. Donald Trump would have loved her. I’m not sure I would have, but I loved reading her story.

Comments