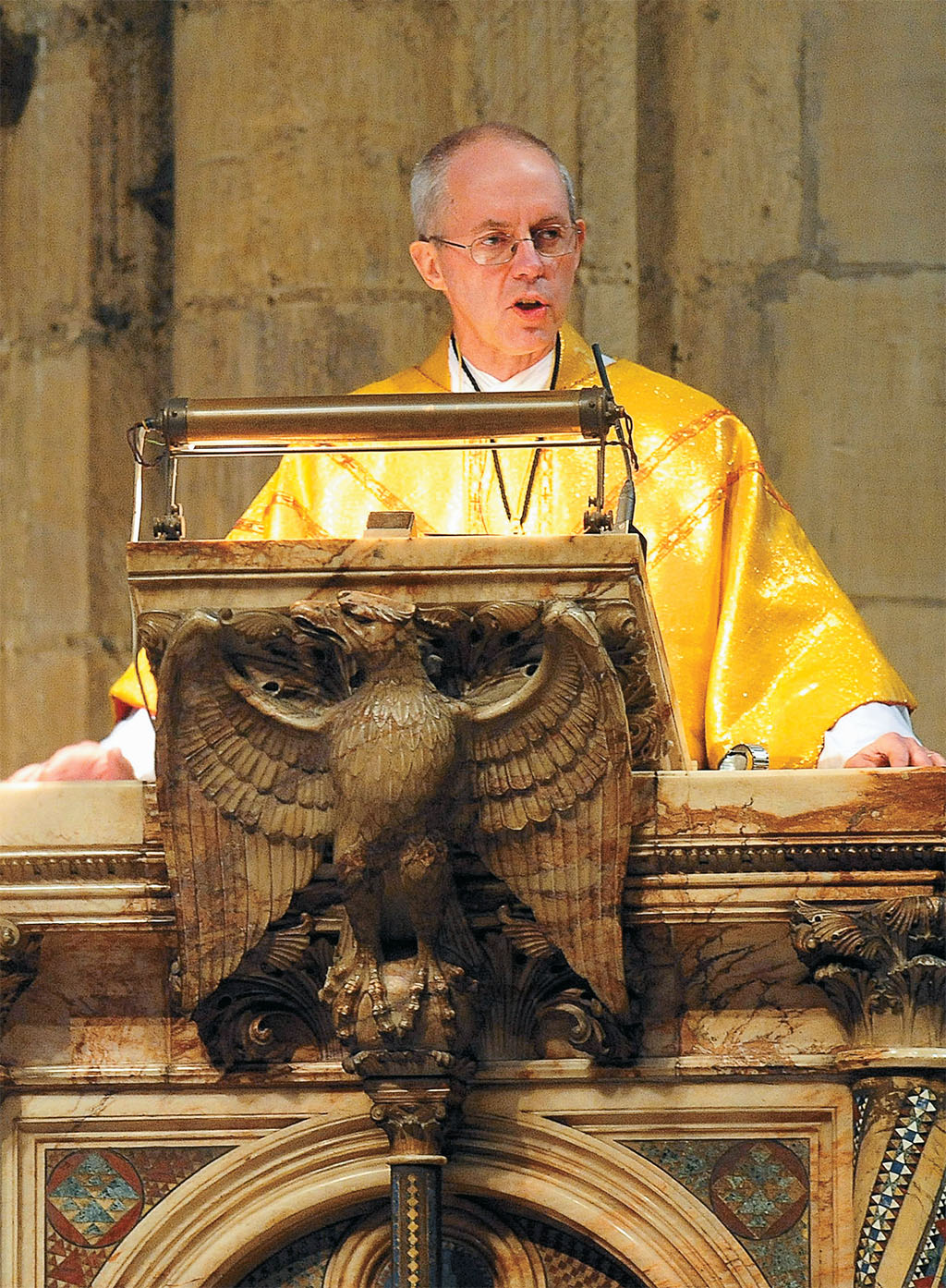

[caption id="WhithertheChurchofEngland_img1" align="aligncenter" width="223"]

COURTESY OF OWEN HUMPHREYS/PA WIRE

THE ELEVATION OF BISHOP of Durham Justin Welby to the Archbishopric of Canterbury is bound to mean changes ahead for the Church of England and the worldwide Anglican Communion. That’s not saying very much. The departing archbishop, Rowan Williams, leaves behind him a controversial legacy. The shepherd’s commentaries on political and social issues have often been at odds with his flock. More seriously, the organizational unity of the Anglican Church has been under serious challenge over such contentious issues as gay clergy and female bishops.

[caption id="WhithertheChurchofEngland_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

In a sense, there’s nothing new under the sun. These potentially fabric-wrenching divides are simply the latest instantiations of different factions within the church that have existed from the 17th-century. It’s often difficult for Americans, even churchgoers, to appreciate the twists and turns of the Church of England, in part because Americans do not have any concept of a national church.

Our Founding Fathers did not intend to banish religion or devotion to a Sovereign God from the public square, but they made perfectly clear that the United States would never recognize the collusion of church and state represented by a national church. And that reflected a totally different worldview from Pre-Reformation Europe. Even throughout the religious wars of the 1500s, Princes assumed they were contending for a national church—be it Roman Catholic or Lutheran.

Through the religious turmoil of the Tudors and the 17th-century Civil War, most partisans contested for a national church. They got one—but none of the parties ended up with an English national church that reflected its own theological or ecclesiastical convictions. Rather, the Church of England that emerged represented a unified ecclesiastical structure with a unified clerical hierarchy, sharing liturgy and canonical practice. What it didn’t represent was shared belief.

From the 18th-century, the C of E has been represented by three principal factions, known colloquially as High Church, Low Church and Broad Church—each with its own doctrine, worship and spiritual emphasis. Since the days of the Georges, it has been clerical hierarchy and a unity of practice rather than of belief that has characterized the unity of the Church of England. “It really doesn’t matter what we personally believe, as long was we all keep the same forms.”

The High Church are the Anglo-Catholics. They see the Anglican Communion as a branch of the apostolic catholic church, believing their priests share apostolic succession with Roman Catholic priests. They also share an elevated sense of the Eucharist, “the real presence” of Christ in the elements and a liturgical focus on the Eucharist. High Church liturgy respects the liturgical solemnity of Catholic worship. This is the tradition of the Oxford Movement, which found its high-water mark in Victorian times.

The Low Church are the descendents of the Puritans, who are decidedly Protestant in their doctrine. These are the evangelicals, who are apt to be more informal and even “contemporary” in their worship, and place an emphasis upon personal faith. This is the tradition of folk like John Newton, George Whitefield and the Wesley brothers.

The Broad Church is the folk whose primary doctrine is the very inclusiveness of the Church of England. These were the squires and trade folk whose attendance at the parish church was for generations simply an accepted part of their English identity. The solemnity and liturgy of the church was part and parcel of their heritage and they are C of E because they are English. These are the true liberals. They welcome all regardless of creed or ethos because the national church and its God is meant to embrace all.

[caption id="WhithertheChurchofEngland_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

It’s an easy matter to identify the dominant loyalties of any given congregation in just a few quick observations in the parish church. The hymnals and songbooks, version of the Bible, literature for sale in a stall or lying around for take-away and display boards all provides clear clues to a church’s identity and vitality.

Though the obvious decline of the Church of England and its influence in society over the last generation has been well observed and documented, that decline hasn’t been evenly distributed across the traditional three “factions” of the Anglican Communion. There are many booming, healthy, vibrant parish churches across Britain. Almost without exception, they are low-church evangelicals, with younger congregations, room for contemporary worship and an active presence in the community. High churches are lower key. Their parishioners are older. Anglo-Catholic churches may be relatively small, but they are generally stable, because their parishioners are devout.

The biggest hit in the Church’s steady loss of numbers and decreased attendance over the last 30 years has come in the Broad Church. As Britain embraced multiculturalism and accepted large-scale immigration of people with other ethnic identities, it became far less automatic to embrace your Englishness in such a nationalistic institution as the church. In a sense, the manor changed hands.

The great sitcom To the Manor Born was gently poking fun of the phenomenon back in the late ’70s. Part of Audrey fforbes-Hamilton’s identity as Lady of the Manor was to fulfill traditional obligations and set a good example in the parish church. Her replacement at Grantleigh Manor, the self-confident Czechoslovakian supermarket magnate, Richard DeVere, neither knows nor cares about these social expectations. With the social expectation gone, and indeed in modern Britain with social expectation, if anything, actively cynical toward church participation, the binding glue of the broad church simply has dissolved. The Broad Church, represented by former archbishop Rowan Williams, has always been seen as the “Establishment.” What they have been left with, however, is the parish caricatured in The Vicar of Dibley.

In these social and doctrinal controversies that have been shaking the Church over the last several years, the traditionalists, in general the evangelicals and Anglo-Catholics, have made common cause. But it is just that, common cause and not an identity merger. Whatever lies ahead for the worldwide Anglican Communion, these parishes will continue to be approaching their own futures in very different ways.

There are delicate times ahead for the Church, and for newly consecrated Archbishop Welby. Certainly more of a traditionalist than his predecessor, Welby is identified as an evangelical. It well may be, though, that it was his negotiating skills and “real world” experience that caused him to rise to the top of the candidate pile for the post.

It remains to be seen how the Church of England will negotiate around these issues; at the end of the day they are real clashes of conscience. Sooner or later, someone is bound raise the possibility that a national church is an idea whose time has passed. That perhaps the time has come to accept that there are indeed three separate churches within the organization and that they need to go their separate ways. Of course, that’s incredibly difficult to imagine. The village pub closing was traumatic enough.

Comments