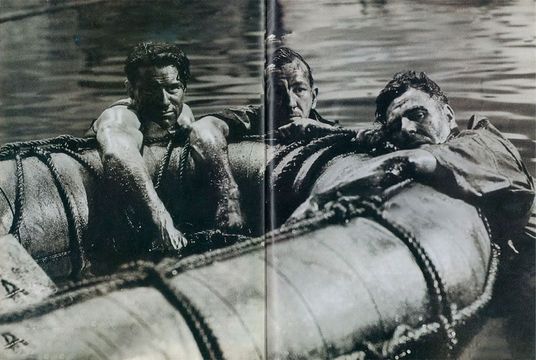

In Which We Serve: John Mills, Noel Coward. and Bernard Miles re-create a dramatic moment in the sinking of HMS Kelly, an actual event upon which the (mostty) historical film was based.

The historical fact often takes a back seat to dramatic conventions when Britain war effort is portrayed on film.

Cinema and history have had an intimate relationship for more than a century. Audiences have become accustomed to accepting what’s on the reel as real. However, when translating historical events onto the screen, storytellers often must deal with events with complexity or lack of dramatic clarity that does not fit neatly into a two-hour feature. Cinematic storytellers sometimes impose their own viewpoints on the historic truth of the tales; characters are composites of real people; time is compressed—or expanded—for dramatic purposes. Necessary exposition, the rise and fall of action, and a satisfactory conclusion all become more important than strict adherence to fact.

“Historical” films U-571 and Enigma, both based on British intelligence operations during World War II, are cases in point. They are only the latest examples of a long history of interpreting the British war effort through film, often for propaganda purposes. World War II was played out in many theatres—Europe, the Pacific, and North Africa. It also was played out in motion picture theatres such as London’s Odeon Leicester Square, the Gaumont Haymarket, the Carlton, and cinemas throughout the U.K.

During the war, documentary filmmakers used footage taken during actual events and edited it to present their cinematic points of view. Films told stories of average families facing the rigours of wartime Britain or the men on the front lines and their women who waited at home. Perhaps the most difficult situations film-makers had to contend with were recounting actual events and the lives of real people.

Propaganda and morale

In terms of propaganda and morale-building, the output of British filmmakers contributed enormously to the war effort. Three films made during the war give today’s audiences a perspective on what was important then: Spitfire (1942), In Which We Serve (1942), and The Way Ahead (1944).

Seemingly everyone wanted to use film to contribute to the war effort. Even those who had not thought of film as an appropriate medium for their talents found their patriotic passions aroused, including theatrical genius Noel Coward. After his great friend Louis Mountbatten described the sinking of his ship, HMS Kelly, off the coast of Greece in May 1941, Coward felt he had his subject—he would tell the story of the ship, its captain, and her gallant crew, and also pay homage to his friend.

Unfamiliar with the film medium, Coward wrote a script that would have run some six hours. Three of the finest British cinematic talents of the time, David Lean, Anthony Havelock-Allan, and Ronald Neame, helped Coward refashion the story of the destroyer, renamed the Torrin, from the laying of its keel to its end at the bottom of the sea.

In Which We Serve stars Coward himself in the role of Captain Kinross. His personal tribute to Mountbatten is reflected in two speeches Mountbatten actually delivered to his crew, one when he welcomes his crew on board and the other when he bids them farewell.

Coward had to wage some personal and political battles in order to get the film made. When Lord Beaverbrook, publisher of The Daily Express and The Evening Standard, learned that Coward would play Mountbatten, his papers took a strong stand against the portrayal of a wartime hero by a foppish matinee idol. Beaverbrook, whom Winston Churchill had appointed Minister of Aircraft Production in May 1940, also thought the idea of a destroyer being sunk by the enemy was hardly appropriate for wartime morale. What was needed, he said, were films about the British vanquishing the enemy.

However, cooler heads prevailed, including that of Lord Mountbatten, who felt the film would enhance the image of the Royal Navy. According to Ronald Neame, “What the government departments failed to realize was that we British are at our best when we are up against difficult situations. Our story is a tale of the devotion and affection of men for their ship.”

In order to enhance the prestige of the film—and, perhaps, boost the confidence of the film-makers that what they were doing was truly worthwhile — Their Majesties King George VI, Queen Elizabeth (the late Queen Mother), and Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret, along with Lord and Lady Mountbatten, visited the set.

The film premiered at the Gaumont Haymarket on 27th September 1 9 4 2—with Beaverbrook’s critics and columnists in the audience. Despite Beaverbrook’s earlier antagonism, his papers gave the film glowing reviews. It, indeed, became the expected morale builder and was credited with increasing enlistments in the Royal Navy.

David Niven (wearing the cap) also starred in the film as the fictional test pilot Geoffrey Crisp.

After making his name as Ashley Wilkes in Gone With the Wind, Leslie Howard returned to England and narrated In Which We Serve. He also appeared in The Forty-Ninth Parallel, Pimpernel Smith, and several war-themed shorts. He followed this with his magnum opus de guerre, Spitfire (also known as The First of the Few), which he starred in, produced and directed. The story of aircraft designer R.J. Mitchell’s life from 1922 to 1940, the film was made at the height of World War II. Like In Which We Serve, Spitfire is told in flashback, in this case by Mitchell’s fictional friend, Geoffrey Crisp, a compilation of several test pilots who flew for Mitchell, especially Jeffrey Quill, who did the stunt flying in the film. (Crisp is played by David Niven, one of many British actors who returned home from Hollywood as soon as the war was declared to do their duty in the front lines of the British cinema.) The film tells the compelling—although romanticized— story of the man who created the plane that won the Battle of Britain. Spitfire has several heroes: Mitchell, his wife, Crisp, the pilots who became the “first of the few,” and the Spitfire itself.

Read more

The film is moderately accurate in terms of history but studio-bound by the pressures of wartime production. Spitfire opens like an old-fashioned high school history lesson with an expository montage of the fall of various European countries, ominous footage, a voice-over quoting Hitler, Goebbels, and Goring, and ending with Churchill’s words: “We shall defend our island. We shall fight on—unconquerable—until the curse of Hitler is lifted from the brow of man.”

© HULTON ARCHVE

Howard portrays Mitchell, and the actor’s slender frame, pale appearance, and pensive demeanour convey the persona of a dreamer and idealist. He says to his wife, “We’ve got to learn from the birds… Wing, body, tail all in one… Someday I’m going to build a plane that’ll be just like a bird.”

Gordon Mitchell remembers speaking with Jeffrey Quill, who chuckled at this scene. He recalls Quill saying, “Your father was a down-to-earth engineer. If he’d had any problem with any of his aircraft, the last thing he would have done is watch some bloody seagulls!”

Later in the film, Mitchell, his wife, and Crisp visit Germany for a holiday. The Germans wine and dine them in the Richthofen Club. Then the women leave and the men remain for port and cigars. The conversation, not unexpectedly, turns to aviation. Mitchell meets Dr. Messerschmitt, who offers him an opportunity to design planes in Germany. A Luftwaffe general at the head of the table says, “You don’t think it’s only gliders we make.”

“But what about the … ? “ begins Mitchell, who is interrupted by the general who says, “You were going to say the Versailles Treaty?”

“Forget it,” says Mitchell, trying to be amiable.

“We have forgotten it!” says the general ominously.

Mitchell grasps that the Germans are building engines not only for commercial aircraft but also for military planes, forbidden by the treaty that ended World War I. The audience and Mitchell—who until now has been the epitome of the naive British gentleman—realize what the British will be facing.

In an aside, Mitchell tells Crisp, “I want to build a fighter, the fastest and deadliest fighter in the world.”

Mitchell’s son roundly disputes this scene. “That was all fictitious,” he emphasizes. “The idea that my father went to Germany, saw what was going on, and rushed back to design the Spitfire is absolute rubbish.”

The pace of the film picks up speed from this point. Obstacles stand in the way of Mitchell’s vision. The government won’t finance the project. Mitchell’s doctor tells him he is working too hard, and if he doesn’t slow down, he has about eight months to live. In truth, Mitchell was diagnosed with cancer and under went colon surgery in 1933. Not a hint of this is included in the film.

Finally, the prototype of the Spitfire is ready, and Mitchell cinematically watches Crisp fly it—doing a victory roll overhead—while confined to a wheelchair at his country home. Mitchell watched the real flight of the Spitfire K5054 on 5th March 1936. Instead of the fictional Crisp at the controls, it was Capt. J. “Mutt” Summers who took those honours. R.J. Mitchell died on 11th June 1937 and never knew that his airplane saved Britain.

Although not strictly a “real to reel" story, The Way Ahead (U.S. title: The Immortal Battalion) is a microcosm of all the elements of a real story. In effect, it was a true-to-life story told again and again throughout the U.K. A group of seven disparate men, including a stoker from the Parliament boiler room, a department store manager, a motor car salesman, a farmer, and a travel agent—characters with whom viewers could identify—are transformed into an organized, heroic fighting unit. Their superiors, Sergeant Ned Fletcher (Billy Hartnell) and Lieutenant Jim Perry (David Niven in another of his wartime roles; he was at the time a major in the British Army), are just as authentic in their roles as the genuine articles were then.

The audience sees the characters before their induction, during training, and with bayonets fixed, charging the enemy. The film, directed by Carol Reed, is tied together by a motif devised by screenwriters Eric Ambler and Peter Ustinov: retired soldiers living at the Royal Hospital remember the good old days of World War I and opine how these youngsters “don’t have the stomach for it.” The pensioners’ comments are counterpoint to the action.

The bickering among the men, rooted in differences of social status and the rigorous training for a big exercise, which they see as a “waste of time,” comes to an end when Lieutenant Perry berates them after they intentionally lose a mock battle. He tells them they are members of the Duke of Glendon’s Light Infantry and what it means to be part of that regiment. He’s not about to let them dishonour the men who served before them at Salamanca, Waterloo, Ypres, and Sebastopol. Even watching the film today, the audience is moved by the force of Ambler’s and Ustinov’s words and Niven’s understated delivery.

Read more

Breaking the silence

At the same time In Which We Serve, Spitfire, and The Way Ahead were being filmed, several thousand people at Bletchley Park struggled to break the German military code based on a complex system of wheels and numbers on the Enigma machine. These men and women, unknown to the outside world until decades after the war, toiled around the clock to intercept, decode, and interpret German military transmissions.

According to Kate Winslet, who stars as Hester Wallace, the fictitious heroine of the film Enigma, “These people were silent for years; they weren’t allowed to talk about their contribution to the winning of the war.”

Enigma, based on Robert Harris’ novel, brings some of this story to light, superimposing it on a fictional plot and characters. The premise of the film is that the Germans have again changed the code and are planning a U-boat attack on a convoy with 10,000 passengers and supplies critical to the war effort.

Tom Stoppard’s script tells a complex story, requiring a great deal of exposition and compelling the audience to follow its twists and turns as it shifts from present to past and back again.

Although the real Bletchley Park was not used in the picture (Chichley Hall, near Milton Keynes, was the stand-in), everything is 1943 accurate. Explains director Michael Apted, “We could have used the real location, but it’s all been built up around the area. I had an aesthetic impulse that I wanted England to look beautiful. I wanted to get a counterpoint between the beauty of the country and the horror going on outside.”

Hut 8, where the cryptanalysts who broke the code laboured, is given a starring role, and the film captures the claustrophobic feel of the environment. Most of the characters—real and fictional—were not trained cryptanalysts but rather everyday people with a penchant for mathematics and puzzles. Although women were involved in the breaking of the code, according to Tony Sale, the consultant on the film and former museum director at Bletchley, no women are portrayed in the eccentric environs of the cinematic Hut 8.

“This was a choice by Stoppard,” notes Winslet. “While we were filming, I met so many women who worked at Bletchley Park who were honoured to be there and doing what they were doing for their country. For years, these women couldn’t talk to their families about what it was they did during the war,” she concludes.

The real hero of the Engima story, Alan Turing, considered the father of the computer and responsible for the breaking of the code, is not a character in the story. He is one of the many people in Scott’s composite character, Jericho.

“Watching people break codes is not particularly interesting,” comments Scott, “but what the film does is give the story some accessibility. My character is complex enough not to patronize what the people did at Bletchley Park. It pays a great deal of homage to them, the bravery and selfless activity.”

Enigma is among the few films in which a mathematical genius plays the hero. Scott researched code-breaking and the Enigma, “taking it apart and putting it back together again.” The pressures on this hero, as was the case in all wartime films, were enormous.

There is enough code-speak and terminology to intrigue the audience. And every message, every transmission, is historically authentic, thanks to Sale.

The story is about brilliant people. “I certainly didn’t want to trivialize what they did nor did I want to make it so difficult that the audience would feel inadequate.” Finding a balance between indicating how complex code-breaking is and giving the characters real qualities was a challenge.

For dramatic purposes, much of the reality of the situation has been ignored, says Apted, “to create something artificial for the greater good. I know it might be confusing to the audience as to what is true and what is not true, but my obligation is to tell the story.”

Although there are compromises in the storytelling, the filmmakers have made an effort to get everything else right, down to an Enigma machine, which is an original four-rotor version owned by Mick Jagger, who plays an uncredited bit in the film.

In the final analysis, Enigma offers the audience history with a dash of romance and a splash of an intellectual test.

In an early scene, a bit of ironic foreshadowing occurs when the travel agent (a George Formby look-alike played by Sid Beck) explains to a couple shopping for a holiday location, “Libya is the only unspoiled playground in the Mediterranean.” Later, this “playground" becomes the site of a battle in which he and his companions will participate.

The real WWII

Like the real soldiers, these “reel” fellows complain about everything from their uniforms (“Wish we wore uniforms with a collar. This makes us feel like convicts.”) to the wait for the fight.

By the time they ship out for North Africa, the seven have become a cohesive fighting unit, all social and personal barriers erased.

The Way Ahead is, of course, propaganda, made at the insistence of the British Army as a morale builder. Brits who saw it in 1944 still consider it the best of the war films.

* Originally published in Nov 2013.

Comments