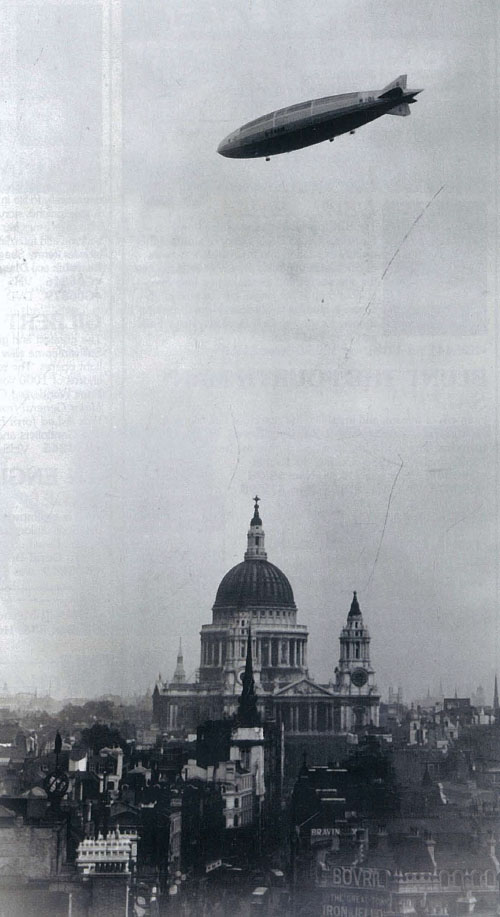

[caption id="AHorribleCrashPutsanEndtoDreamsofLighterthanairTravel_img1" align="aligncenter" width="500"]

HULTON/ARCHIVE BY GETTY IMAGES

IT ISN’T EASY PUSHING FORWARD the frontiers of technology, but sometimes overcoming old-fashioned human pride proves an even greater challenge. The crash of the R101 airship, unlike the sinking of RMS Titanic 18 years earlier, was not a case of an unthinkable and unexpected tragedy but one that many people must have anticipated. Still, with a determination that went beyond courage into the realm of foolhardiness, the airship’s creators pressed on rather than admit defeat.

From the perspective of the 21st century, lighter-than-air transportation evokes images of lumbering, unwieldy craft resembling, in size as well as manoeuvrability, nothing so much as a beached whale. But in the years following World War I, such technology was more than cutting edge; it was still an unfulfiled dream of a new generation of designers.

Conventional aircraft had proved their reliability during the war, but they guzzled petrol and carried such small loads that their commercial potential looked very limited. Dirigibles seemed the way of the future.

Frustratingly for British engineers, Germany, the vanquished power in the Great War, was outdoing the victors in developing the new technology. So in 1924 the British Airship Programme undertook the production of a state-of-the-art British airship in an effort to close the technology gap. Everyone agreed that that would be a good thing; debate arose, however, over the question of whether Government or private enterprise should lead the effort. In the end, both sectors would get their chance. The Airship Guarantee Company, Limited, a subsidiary of Vickers, was commissioned to build R100, and the Air Ministry would simultaneously design and build a second airship, designated R101.

Both airships were required to be capable of speeds up to 70 miles per hour and to accommodate 100 passengers. Each was to weigh no more than 90 tons and be able to lift 60 tons of crew, passengers, cargo, and supplies.

An immense challenge faced both teams. Because the specifications were, I beyond anything that anyone had ever before built, there were no precedents to follow, and the best-laid plans often produced unexpected results. The engines chosen to power R101 provide just one example of this. The R101 design team modified engines originally made for diesel locomotives, but their bulk proved problematic for a vessel whose net weight needed to be lighter than air. What’s more, they were so powerful that the propellers they drove tended to self-destruct under the torque imparted to them. Modifications made the engines useable—under ideal conditions—but by the time the engineers had finished all the necessary adjustments, the R101 was no longer able to achieve the top speed demanded by the specifications.

THE DIRECTOR OF AIRSHIP DEVELOPMENT REPORTED, IN EFFECT, THAT APART FROM EVERYTHING THAT HAD GONE WRONG, R101 PERFORMED WELL.

Problems such as these delayed the ship’s construction and, in turn, its launch, which had been scheduled for early in 1927. In fact, it was October of 1929 before R101 was ready for testing. The long delay might easily have been forgiven if it had resulted in a ship that had finally met all of her design specifications. Far from it. The new airship could lift only 35 tons, barely half the weight required. On her first test flight, only two of her five engines performed reliably. As if this was not enough, it quickly became evident that turbulence caused by foul weather made the airship’s internal hydrogen bags rub against the vessel’s metal support girders, resulting in leaks. All in all, very little about the airship was working out as hoped.

These performance problems also led to a public relations dilemma. The ship was to have been the symbol of a new leading role for British aviation in the eyes of the world. Instead, she was becoming a significant embarrassment. While the technological problems might eventually be worked out, every delay made the Air Ministry look less capable of fulfilling its mission. The pressure on the Ministry only increased when R1OO, the privately built companion to R101, crossed the Atlantic and returned safely. R101 had to fly, and soon.

[caption id="AHorribleCrashPutsanEndtoDreamsofLighterthanairTravel_img2" align="aligncenter" width="576"]

HULTON/ARCHIVE BY IMAGES

To try to rebuild public confidence in the airship program, the Air Ministry planned to feature a flight of the R101 at the Hendon Air Show in June 1930. The demonstration served only to highlight further deficiencies. In the days leading up to the air show, the ship’s canvas skin tore in several places and had to be hastily patched. Then, during the event itself, R101 developed more gas leaks and was barely able to stay aloft, despite releasing much of its water ballast over the crowd of spectators.

To remedy the lift problem, the designers sliced her in two and inserted an extra section of superstructure in the middle, which made room for an additional gas bag. The work was rushed for completion by 1st October, so that the ship would be ready in time to carry the Air Minister, Christopher Thompson, on a high-profile trip to India. But before such a flight could depart, R101 had to pass a 24-hour flight test and be certified as airworthy by the Aeronautical Research Committee.

Apparently, the certification was a foregone conclusion, because after a 17-hour flight plagued by engine trouble, R101 was declared ready for service. The Director of Airship Development at the Royal Airship Works reported, in effect, that apart from everything that had gone wrong, R101 performed well. It almost seems as if no one could imagine a greater public relations disaster than having the great airship fail its certification test, and since the technical problems had proved so difficult to solve mechanically, the inspectors simply certified that, officially, the problems did not exist. The flight to India would leave as planned.

As THE UPCOMING FLIGHT WAS seemingly inevitable, those in the know about the airship’s deficient lift capacity might reasonably have been expected to exercise appropriate caution. The Air Minister himself, however, loaded some 30 pieces of luggage—more than a ton—onto the airship for his jaunt to India. To ensure sufficient lift, R101’s gas bags were filled to near maximum capacity, giving the ship more buoyancy but virtually ensuring that the troublesome bags would again rub against the ship’s metal struts and begin to leak.

Most of those who had flown in R101 during the test surely must have known that she was a very unsound vessel and had barely survived short trials under ideal conditions. The likelihood that she could reach India without mishap must have seemed remote. Yet nothing could stop the flight that, if successful, would place the Air Ministry in the forefront of a technological revolution. She cast off from the mooring mast and set out on her maiden voyage on the evening of 4th October.

Early the next morning, R101 crashed into a hillside near Beauvais, France, and burst into flames. Of the 54 crew and passengers, only six survived. As none of the survivors were in the control gondola at the time of the crash, it is impossible to know exactly what happened. Most likely, stormy weather during the flight caused the airship to roll like an ocean-going vessel in high seas. This would have made the gas bags rub as they had during test flights. If the outer skin had torn again, wind blowing into the ship’s interior would have made it even wobblier, further increasing the likelihood of ruptured gas bags. As gas leaked, R101 would have lost buoyancy and been unable to maintain altitude. Upon hitting the ground, or maybe just before, a spark from one of the balky engines probably ignited the leaking hydrogen.

After a six-year building programme costing £1 million and 48 lives, R101’s place at the pinnacle of the aviation world had lasted just seven hours.

Comments