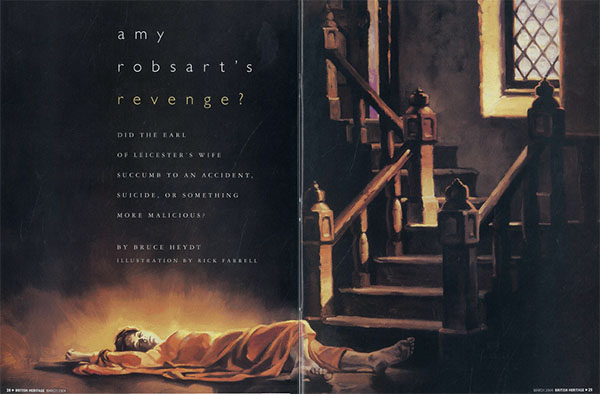

DID LEICESTRE’S WIFE SUCCUMB TO AN ACCIDENT, SUICIDE, OR SOMETHING MORE MALICIOUS?

[caption id="AmyRobsartsRevenge_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

HISTORY, IT SEEMS, isn’t always written by the winners. Sometimes it is written by a vocal opposition with an axe to grind. The problem for later generations of researchers is that while this may make such histories of doubtful accuracy, it does not necessarily make them untrue. And at times, it’s nearly impossible to see clearly through the mists of time and discern just where truth ends and slander begins. In the case of the unfortunate death of Amy Robsart (and regardless of what else you may believe, we can at least agree that it was unfortunate), the controversy surely did not begin with the document known as “Leicester’s Commonwealth,” but it therein took on its most tangible and full-bodied form. Leicester’s Commonwealth accused Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester, of having planned the death of his wife, Amy Robsart, some 24 years earlier, so that he would be free to marry his new paramour, Queen Elizabeth I.

By the time Leicester’s Commonwealth appeared, the mystery of Amy’s death was already widely known and had probably begun to fade from the public’s consciousness—good enough reason for enemies of Robert and the Queen to stir up the waters again. The key facts surrounding Amy’s death were suspicious but inconclusive. Robert and Amy had been married on 5th June 1550. Robert was the son of John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, while Amy was the daughter of Sir John Robsart, Lord of the Manor of Syderstone, Norfolk. The union was notable enough to prompt the attendance of King Edward VI.

Little is known of the character of the 18-year-old bride. She was regarded as charming and quiet, and it might also be deduced that she was less ambitious than her husband, whose political intrigues seemingly resulted in his having little time to spend with his bride. Upon the death of the young King, Robert’s involvement in the scheme to place Lady Jane Grey on the throne resulted in his imprisonment in the Tower of London and indeed a death sentence. Though he eventually received a pardon, he soon departed for France, where he served as Master of Ordnance for the English army at the Battle of St. Quentin.

When Queen Elizabeth took the throne, Sir Robert’s fortunes rose yet again. Elizabeth made him a Knight of the Garter and Master of the Queen’s Horse, a position that required his close proximity to the Queen on a daily basis. The “promotion,” an important step for a courtier as ambitious as Robert, had more ominous implications for Amy. Almost immediately, rumours began to circulate that the Queen’s favours to Robert extended beyond just titles and grants of land. In 1559 the Spanish ambassador to Elizabeth’s court, Don Gomez Suarez de Figueroa Feria, wrote to, his King that “Lord Robert has come into so much favour that he does whatever he likes with affairs, and it is even said that her Majesty visits him in hjs chamber day and night. People talk so freely that they go so far as to say that his wife has a malady in one of her breasts and the Queen is only waiting for her to die to marry Lord Robert.”

The contents of this correspondence could not have been publicly known at the time, but it hardly seems to have mattered. Whatever the Spanish diplomatic corps thought about the matter privately, the affair between Queen and courtier seems to have been so generally acknowledged that gossip about it surely reached the ears of Robert’s wife, who was residing at Cumnor Place in Berkshire. Amy’s state of mind during this time, about 1560, was one of “desperation,” or so one of her maid9 claimed that Amy herself Mad said. This may have been caused by the thought of her frequently absent husband’s notorious “audiences” with the Queen in his, own bedchamber, by the illness she allegedly suffered, Or by a fear that more malevolent forces were at work.

ON 8TH SEPTEMBER 1560, Amy’s foreboding apparently proved itself justified. Thomas Blount, an associate of Robert’s who was travelling on business for him, encountered a servant of Amy’s named Bowes, who brought the news that Amy had fallen down “a pair of stairs” and was dead. This news set off a chain of speculation, rumour, accusation, and “spin doctoring” that had still not run its course 24 years later when Leicester’s Commonwealth explicitly accused Robert (and implicitly the Queen) of arranging Amy’s murder.

The Leicester’s Commonwealth’s interpretation of the events surrounding Amy’s death found its way into Elias Ashmole’s Antiquities of Berkshire, and then into Sir Walter Scott’s Kenilworth, despite the latter author’s own admission that “slander, which very seldom favours the memories of persons in exalted stations, may have blackened the character of Leicester with darker shades than really belonged to it.”

[caption id="AmyRobsartsRevenge_img1" align="aligncenter" width="450"]

SOUTHHAMPTON CITY ART GALLERY/BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY

In fact, the report could hardly have been any blacker. According to this detailed and seemingly authoritative account:

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester … it was thought, and commonly reported, that had he been a bachelor or widower, the Queen would have made him her husband; to this end, to free himself of all obstacles, he commands, or perhaps, with fair flattering entreaties, desires his wife to repose herself here at his servant Anthony Forster’s house [Cumnor] … and also prescribes Richard Varney (a prompter to this design), at his coming hither, that he should first attempt to poison her, and if that did not take effect, then by any other way whatsoever to dispatch her.

IN CONSEQUENCE OF THESE INSTRUCTIONS from Robert, Varney allegedly sent a messenger to a physician in Oxford, named Bayly, with the intent of obtaining “some little potion,” ostensibly to ease the melancholy from which Amy was suffering, but to which the conspirators planned to “add something of their own.” Bayly, the story goes, refused to prescribe any medication, suspecting what was intended and fearing that he would become the scapegoat after the murder was committed.

Failing to obtain a potion that they could spike, Verney supposedly had no choice but to fall back on “any other way whatsoever” to ensure Amy’s demise:

Sir Richard Varney … by the Earl’s order, remained that day of her death alone with her, with one man only and Forster, who had that day forcibly sent away all her servants from her to Abington market, about three miles distant from [Cumnor); they (I say, whether first stifling her, or else strangling her) afterwards flung her down a pair of stairs and broke her neck, using much violence upon her ….

[caption id="AmyRobsartsRevenge_img2" align="aligncenter" width="225"]

LELTON BERQUEST/BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY

THIS STORY, TO WHATEVER EXTENT it might be believed, could not fail to embarrass both Robert and the Queen. But there are serious questions about its veracity. By the time it appeared in published form, there was already a history of using Amy’s untimely death to gain political and economic advantage.

Amy’s half-brother, John Appleyard, prov, ed to be the most opportunistic of the scandal-mongers. Following Amy’s death, Robert granted Appleyard several choice appointments, which might look suspicious in retrospect, if not for Appleyard’s subsequent actions, which proved him to be nothing but a conniving schemer trying to milk the awkward situation for his own benefit. The poor grieving brother accepted all Robert’s beneficence until he decided that, with the proper form of persuasion, the Earl could do even more to advance his career. The brand of persuasion he settled on was blackmail. He hinted that he knew more than had been revealed about his sister’s death, and that he would tell all. He may have acted on his own initiative, although he claimed to have been urged on by a mysterious cabal of disgruntled courtiers. Appleyard made out that the jurors who had investigated the incident had been bribed to return a verdict favourable to Robert.

Appleyard appeared before the Privy Council in May 1567 to repeat his version of the story, but judging from the fact that he was subsequently imprisoned, it seems the enquiry probably had more to do with defending himself against charges of perjury and slander than with bringing charges of his own against Robert. While in gaol, Appleyard recanted his story, decided that Robert was probably innocent after all, and admitted that he had been blackmailing him.

TRIANGLE OF LOVE

[caption id="AmyRobsartsRevenge_img3" align="aligncenter" width="93"]

PRIVATE COLLECTION/BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY

[caption id="AmyRobsartsRevenge_img4" align="aligncenter" width="96"]

PRIVATE COLLECTION/BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY

TO SHIELD THE QUEEN

In this compelling debut of her historical mystery series, Fiona Buckley introduces Ursula Blanchard, a widowed young mother who has become lady-in-waiting to Queen Elizabeth I. Armed with a sharp eye, dangerous curiosity, and uncanny intelligence, Ursula pledges … “To Shield the Queen.” Rumor has linked Queen Elizabeth I to her master of horse, Robert Dudley. As gossip would have it, only his ailing wife, Amy, prevents marriage between Dudley and the Queen. To quell the idle tongues at court, the Queen dispatches Ursula Blanchard to tend to the sick woman’s needs. But not even Ursula can prevent the “accident” that takes Amy’s life. Did she fall or was she pushed? Ursula sets out to find the truth in a glittering court that conceals a wellspring of blood and lies. 336 pages, paperback. ITEM: #BHSQ $9.99, Includes S&H

THE DOUBLET AFFAIR

Return to the glamorous court of Queen Elizabeth I in this historical mystery—the sequel to To Shield the Queen. Elizabethan sleuth Ursula Blanchard poses as a governess to gather information on a conspiracy involving a London clock maker. 416 pages, paperback. ITEM: #BHDA $9.99, includes S&H

Order both books (ITEM: #BHSD) for $17.98, Includes S&H

Order online:

www.TheHistoryNetShop.com

Order by Telephone:

1-800-358-6327

Order by Mail:

British Heritage Products, PO Box 1539, Fort Lee, NJ 07024

[caption id="AmyRobsartsRevenge_img5" align="aligncenter" width="227"]

[caption id="AmyRobsartsRevenge_img6" align="aligncenter" width="228"]

LETTERS WRITTTEN WITHIN DAYS of Amy’s death paint a different picture of the events than those created years later by either Appleyard or the writer of Leicester’s Commonwealth. Admittedly, many of these letters were penned by Robert himself and could not be expected to reveal anything that would explicitly cast suspicion upon him, but neither do they seem to be the product of someone trying to cover his tracks. Rather, they are the sort of anxious epistles you would expect from a man who was keenly aware that his wife’s death at such an unseemly hour would cause suspicion, and that he needed to cooperate in1the investigation to the fullest extent to avoid any appearance of guilt.

On the day following Amy’s death, Robert wrote: “By [Bowes] I do understand that my wife is dead and, as he saith, by a fall from a pair of stairs. Little other understanding can I have from him.” He sent Blount to Cumnor to ascertain the details. Robert himself did not attend Amy’s funeral. While this may seem cold-hearted, it is not the sort of behaviour that a killer masquerading as a grieving husband would likely have risked. Rather, Robert’s letters seem to suggest that he was walking a fine line between cooperating with the investigation and seeming to interfere or influence jurors by his presence.

From Cumnor, Blount wrote: “My lady is dead, and, as it seemeth, with a fall, but yet how, or which way, I cannot learn.” Presumably this was due to a lack of eyewitnesses, for, as Leicester’s Commonwealth would later accurately report, most of the servants had been sent off to Abington market. According to Blount, however, this was done not at Forster’s insistence, but by Amy herself, who was very angry with the few who declined to go. Of Varney, the prime mover of the Commonwealth account, there is nothing in the contemporary records to prove he was even present.

Blount’s next letter, written two days later, reveals that murder seems to have been, at best, a remote possibility: “I have almost nothing that can make me so much to think that any man can be the doer of it …. The circumstances and the many things which I can learn doth persuade me that only misfortune hath done it and nothing else.” Unfortunately, Blount failed to elaborate on those “many things.”

Robert himself wrote to the coroner’s jury, urging them to take all the time they needed to make a just decision. To Blount he wrote: “I am right glad they be all strangers to me,” so that there would be no hint of impropriety.”

THERE IS ANOTHER, much simpler reason, for doubting the story contained in Leicester’s Commonwealth. It seems likely that the writer of that account, working so many years after the event, was unaware that the flight of stairs on which Amy had her fatal fall consisted of only eight steps, according to a contemporary description of Cumnor Place, which no longer stands. (A flat square landing divided the staircase into two parts, which accounts for the description of it as a “pair of stairs.”) While it is certainly possible that a fall down such a set of stairs might break a young woman’s neck, it’s hard to believe that anyone pushing her would have been foolish enough to depend on it, or even that anyone who might have first strangled her and then thrown her down—the stairs to create the appearance of an accident could have rested secure in the belief that such an unlikely manner of death would not spawn suspicion. Most improbable of all is the assumption that anyone might attempt suicide by tumbling down a mere eight steps.

It takes some imagination to picture even an accidental fall happening in such a way that Amy would not have saved her life by the inevitable reflex action of extending her arms to absorb the impact, perhaps at the cost of a broken bone or two. It might be reasonable to suppose that Amy was ill, as was rumoured, and in a moment of delirium-or maybe needing assistance but finding no one within earshot in the nearly empty house-she wandered to the top of the staircase, where, weakened by the exertion, she fainted.

If so, there is a macabre irony to her demise, for by expiring in a way that cast suspicion upon her husband, and which thus made his marriage to Elizabeth politically untenable, she quite unintentionally had her revenge against him for his marital infidelity.

Comments