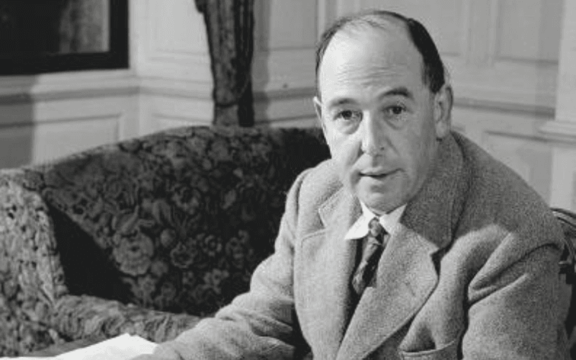

C.S. LewisGetty

C.S. Lewis is a British icon

In 2013 a memorial was unveiled in the famous Poets’ Corner—the north transept of Westminster Abbey. C.S. Lewis joined the chorus of timeless bards and sages stretching back to Geoffrey Chaucer beside the likes of John Donne and Tennyson, Wordsworth, the Brontë sisters, and other newcomers such as T.S. Eliot and W.H. Auden.

C.S. Lewis may have more hardcore fans for more different reasons than any other writer of the 20th century. Three generations of children have passed through the wardrobe, losing themselves with delight in the possible world of The Chronicles of Narnia.

Read more

Countless questers have found their faith or found it more sharply defined by the mere Christianity of a score of literate, reflective books that mark Lewis as perhaps the most effective Christian apologist of the century. Science fiction and fantasy buffs regularly include his “Space Trilogy” in their classical canon. There are Lewis books of poetry, psychology, and philology as well.

Of course, those were all side interests for Lewis, who was one of the premier Renaissance literature scholars of his generation.

Known to one and all as “Jack,” Clive Staples Lewis was born in Belfast in 1898, but will always be a writer associated with Oxford. Lewis’ father was a prominent attorney. He lost his mother at an early age and spent a peripatetic boyhood being educated in England, arriving at Oxford in 1916.

With a break in the trenches of France during the Great War, Oxford was home for the rest of his life. After earning triple firsts, Jack Lewis was made a fellow of Magdalen College in 1925. He remained on the Magdalen faculty until 1954 when with some reluctance he accepted the role of Professor of Medieval and Renaissance Literature at Cambridge.

Throughout Lewis’ adult life the companion with whom he shared his home and his world was his older brother, Major Warren “Warnie” Lewis. Together, they kept house in the suburb of Headington and a quasi-rural retreat in a rambling manor called “The Kilns.” They shared the house with Mrs. Moore, the mother of a friend of Lewis’ killed in the war. During the week, however, Jack Lewis generally stayed at his rooms in college, the New Building tucked next to the River Cherwell in the Magdalen College close.

Oxford and "The Inklings"

Lewis began his way through the rarified world of Oxford academia and its politics as a fashionable atheist. Oxford, however, is hardly the place for any belief to go unchallenged, and the atheism of a young literary tutor was no exception. As way leads on to way, through the early years of the 1920s Lewis found himself confounded by the claims of Christian.

His closest friend and colleague became J.R.R. Tolkien, an Anglo-Saxon scholar at Merton College, just across the High Street from Magdalen. From the early 1930s through the 1940s, they became the bright lights of a changing, informal coterie of men who casually referred to themselves as the Inklings.

Over the years its membership included such writers and scholars as Owen Barfield, Neville Coghill, Hugo Dyson, Charles Williams, John Wain, and many others. The one constant figure was Warnie Lewis, whose diary became the de facto journal of the Inklings’ proceedings.

On Tuesday evenings, the group would gather in Lewis’ rooms at Magdalen to share their “work in progress,” reading aloud to the company from their current writings—and following the conversational tangents where they led. There was a jug of beer on the table, and copious cups of tea were gulped through the blue haze of tobacco smoke.

Thursday mornings the Inklings gathered at the Eagle and Child pub across from the Martyr’s Memorial on St. Giles to drink beer and talk ideas. No, this wasn’t beer for breakfast. Opening time was 11 a.m. and a “morning session” ended when the pub closed for the afternoon at 2 p.m. No known record exists of how much beer was routinely consumed. From that cauldron, however, Lewis and his mates brewed their imaginative worlds, argued moral philosophy and literary theory, and drew sides in the academic politics of the day.

To this day, the pub known to the Inklings and their legion of worldwide fans as “the Bird and Baby” remains the “must-see” sight on a visit to Oxford. Black and white photos of Jack Lewis, Warnie, Tolkien, Williams and mates hang on the dark walls in the snugs where they raised their pints and smoked their pipes. In fact, Oxford is littered with pubs where in twos and threes Lewis shared beer and conversation: the Eastgate Hotel and the Mitre on the High Street, and the famous Turf Tavern (later frequented by Inspector Morse).

The “City of Dreaming Spires” hardly needs C.S. Lewis as a drawing card. The much-loved author does, however, bring thousands of visitors from across the globe every year. Like many Oxford colleges, Magdalen is open to visitors most afternoons from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. Their ancient quads and chapels echo with centuries of academic promise and social history. The gentlemen at the Porter’s Lodge at Magdalen College maintain, though, that its association with C.S. Lewis is the principal reason why visitors today specifically seek out a visit to Magdalen.

Lewis’ home in the suburb of Headington, known as The Kilns, is now a residential study center for visiting writers and Christian scholars.

Another regular stop for Lewis’ fans is the nearby University Church of St. Mary’s, where at the beginning of World War II Lewis preached a famous sermon titled “The Weight of Glory,” from a pulpit shared by such figures as John Henry Newman and Desmond Tutu.

The success that C.S. Lewis enjoyed as a writer with popular books as diverse as The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and his deeply personal A Grief Observed was not without controversy among his academic colleagues. After all, scholars were supposed to produce scholarship, not become famous. Lewis’ very popularity was somehow not “on” for Oxford’s crusty reputation—a sign that he was not quite serious.

In actuality, however, Lewis built an academic reputation early with The Allegory of Love, still the benchmark study of medieval courtly love. Late in his career, he published The Discarded Image, drawn from his popular lectures on how the medieval world view was supplanted by the Reformation and the Enlightenment. Among his works whose enjoyment is largely confined to literary students, Lewis’ masterpiece is his 700-page study English Literature in the Sixteenth Century for the Oxford University History series.

Exploring Lewis

A legion of websites offer information on C.S. Lewis and on visiting the vibrant university city of Oxford. Fans might like to discover the C.S. Lewis Foundation site at www.cslewis.org.

Always a private man, later in life Lewis slipped into a relationship with a woman, an American fan of his writings who crossed the Atlantic to see him. Joy Davidman ultimately became his wife and joined the brothers at The Kilns. Lewis’ new domestic joy lasted only a few years, however, and Joy died of cancer in 1960. Lewis’ pain and processing was recorded as A Grief Observed, the most personal of his books and the only one published originally under a pseudonym. The story of their relationship has been retold in the book and film Shadowlands.

3

3

DANA HUNTLEY

DANA HUNTLEY

Jack Lewis, his brother, and varying companions relished walking holidays together. Among their favorite routes were the Malvern Hills, where Lewis spent a year in school preparing for Oxford. Across the bridge on the A449 in Great Malvern, the sidewalk is lit by a string of Edwardian gas lamps to this day. Walking along with his brother on a snowy night, Lewis paused in front of one such lamppost and remarked, “That would make a great opening scene for a book.” And the rest, as they say, is history.

In all, Lewis published 52 books as well as countless essays, articles, and letters. The author died at home at The Kilns at 65 of a weak heart and sundry complications. Lewis maintained that he had done what he wanted to do and was ready to go. Lewis is buried with his brother at Holy Trinity churchyard in Headington Quarry, the parish church where they regularly attended services for years. In the church, generally open, due attention is paid to its most famous parishioner, and visitors love the Narnia Window in his memory.

Tucked away across the busy A4142, The Kilns is today owned by the C.S. Lewis Foundation and maintained as a residential study center for Christian scholars and writers on stays in Oxford. Though the house is not open to the public, you can follow past it off Kiln Lane to the C.S. Lewis Nature Reserve, a public oasis in spreading metropolitan Oxford—which was once part of his back garden.

In the half-century since Lewis’ death, there has been no diminution in his popularity as a writer. Virtually all of his books remain in print, and each somehow becomes important in its own way to the reader who discovers it. Studies, reflections and personal accounts of C.S. Lewis’ life and works number in the hundreds. To compare Lewis to other writers and to trace his considerable influence as an author and intellect is their province. Anyone who has had an “Aha!” moment with C.S. Lewis or met Tumnus at the lamppost, though, knows his place in Poets’ Corner was reserved.

* Originally published in 2018

Comments