Supporting Faith and Fabric in Salisbury

[caption id="CathedralsinCrisis_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

COURTESY OF SALISBURY CATHEDRAL UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED

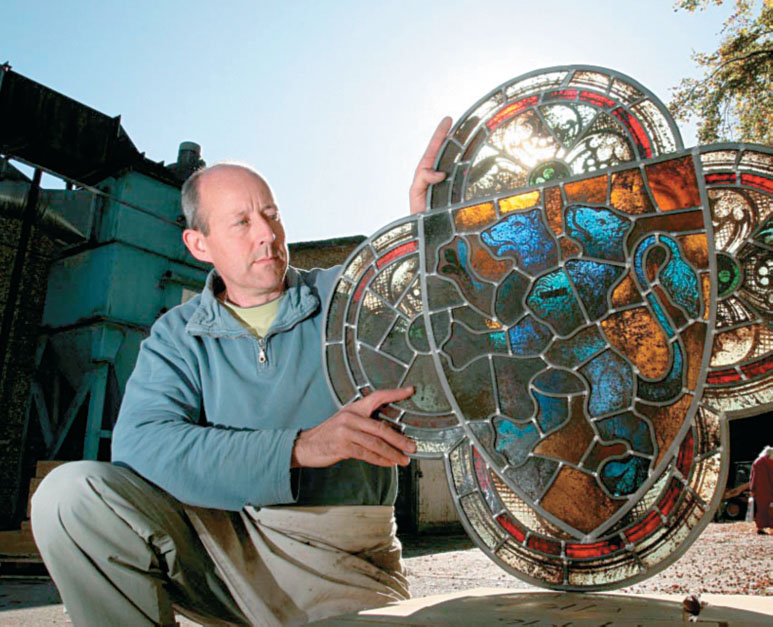

“You’ve really got to admire the original medieval glaziers, cutting glass by touching it with a red-hot poker to create a crack, then working each piece with just a grozing iron. They were incredibly accurate—though you do come across one or two oddments, like somebody’s medieval fingerprints in the paintwork that has been fired into the glass!” So says Sam Kelly, head glazier at Salisbury Cathedral

Kelly arrived as an apprentice in 1977 and has led the Glazing Department here since 2000. The four-strong team has in its care three-quarters of an acre of glass, from medieval to modern, in a reputed 365 windows. They’re certainly kept busy, releading and conservation cleaning.

There’s some £768,000 of glazing work to be done between now and 2018 as part of Salisbury Cathedral’s major repair program. Kelly’s department drums up some money by doing work for outside organizations, turning over £170,000 a year and making a 10-15 percent profit to plough back into cathedral coffers. But there’s still funding to be sought.

Several months ago a report by English Heritage set alarm bells ringing across the country. The good news, it said, was that the majority of England’s 61 Anglican and Roman Catholic cathedrals are in better physical condition than they have been for a century, thanks to £250m of repair work since the early 1990s. The bad news? That six cathedrals—Canterbury, Chichester, Lincoln, Salisbury, Winchester and York—need to find another £60m between them over the next 10 years. Moreover, due to a government spending squeeze, English Heritage ring-fenced funds that guaranteed £3m a year for cathedral repairs have been scrapped.

So who pays to maintain and enhance England’s glorious cathedrals?

It was with this question in mind that I had come to The Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Salisbury, Wiltshire. Before I went behind the scenes I “did” the visitor experience in the company of cheerful volunteer guide Caroline Waldman, a retired nurse. More than 600 volunteers help out here, from guides to “holy dusters.”

The cathedral is unusual in that it was built all in one architectural style—Early English Gothic. The foundation stones were laid in the meadows beside the River Avon in 1220, after the decision was taken to decamp from the cramped Norman cathedral at nearby Old Sarum. The church at “New Sarum” was consecrated in 1258, and the Chapter House and cloisters completed in 1266.

Speak it quietly: a high water table hereabouts meant those crazy medieval builders could excavate down just 4 feet, but luckily for them there’s also a 27-foot layer of flint gravel with water flowing through: helping to prevent the cathedral from toppling. When Salisbury’s famous spire was added around 1310-1330 (Britain’s tallest at 404 feet), another 6,500 tons pressed down on the doughty Purbeck marble columns of the spire crossing: look up and you can see them bending.

“The spire leans just under 29 inches to the south west, but it is safe,“ Waldman smiles. For good measure we trotted the 332 steps up the tower, past all sorts of clever wood and ironwork that keeps it standing, for spectacular panoramas over city and countryside. As we caught our breath, Waldman told me about the abseiling conservators who every now and then dangle down from the tower carrying liquid cement on their backs. “If they spot something that needs repair, they get out their trowels.”

[caption id="CathedralsinCrisis_img1" align="aligncenter" width="944"]

COURTESY OF SALISBURY CATHEDRAL UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED

Back on terra firma, there’s a tremendous amount to enjoy and, true to the cathedral’s ethos as a dynamic worshipping community, treasures span the centuries to the present day. In the Trinity Chapel a medieval stone coffin lid marks the site of the shrine of St. Osmund, bishop at Old Sarum, 1078-99, and early promoter of the cathedral’s core values: community, hospitality, worship and education. Opposite the north porch entrance, William Pye’s wonderful 3m-wide patinated bronze font (2008) calmly reflects the cathedral’s stained glass and nave vaulting.

There’s England’s earliest complete set of surviving choir stalls (1236) and one of Europe’s oldest working clocks (1386), Britain’s largest cathedral cloisters and, in the Chapter House, the best preserved of only four surviving examples of Magna Carta (1215). All this, and more, set in the idyllic 80-acre Cathedral Close, the largest in Britain.

It costs £14,000 a day to run and maintain Salisbury Cathedral, a tough call at a time when the media love to remind us that Britain is an increasingly secular society, with church attendance in decline. Yet at the last national census 72 percent of the population claimed to be Christian, and various studies, when they pop up, show that people continue to value the reassuring presence of churches in our landscape.

I sat down to refreshments in the refectory restaurant with the dean, The Very Reverend June Osborne, marketing and communications director David Coulthard and Sarah Flanaghan, communications and public relations. I asked them: Why do visitors come to the cathedral?

Let’s be frank. The earliest pilgrims, spurred by religious faith, were pioneers of tourism, and abbeys and cathedrals were eager for their business. Salisbury promoted the cult of St. Osmund, but it never caught on in the way of, say, Becket at Canterbury. What did catch the imagination and increase was the cathedral’s role as a place of architectural pilgrimage, with Sir Christopher Wren describing it in 1688 as “one of the best patterns of architecture in the age wherein it was built.”

The romantic revival of interest in all things Gothic in the 18th–19th century, coupled with J.M.W. Turner’s and John Constable’s views of the cathedral in its meadow setting, sealed the deal of a perfect vision of England. Visitors from 1865 happily paid sixpence for a trip around the choir, Chapter House and cloisters.

The cathedral recently carried out a survey among 250,000 tourist visitors, and Coulthard reveals that nearly 40 percent come from overseas (almost half of those from North America). Top reasons to visit are an interest in history, churches and architecture (60 percent), followed by a desire to see Magna Carta. Around 9 percent come for prayer or a spiritual experience. Entrance to the cathedral is free, but a voluntary donation (adult £5.50) is suggested; I’m surprised that a good 30 percent or more decline, supporting neither faith nor fabric.

[caption id="CathedralsinCrisis_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

COURTESY OF SALISBURY CATHEDRAL UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED

[caption id="CathedralsinCrisis_img3" align="aligncenter" width="789"]

COURTESY OF SALISBURY CATHEDRAL UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED

[caption id="CathedralsinCrisis_img4" align="aligncenter" width="772"]

COURTESY OF SALISBURY CATHEDRAL UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED

[caption id="CathedralsinCrisis_img5" align="aligncenter" width="773"]

COURTESY OF SALISBURY CATHEDRAL UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED

‘SO, IS THERE FRICTION BETWEEN ITS MORAL CHRISTIAN PURPOSE AND THE IMPERATIVES OF MODERN BUSINESS?’

The cathedral shop and refectory—worth visiting to gaze through the glass roof at the spire, never mind the coffee and cakes—together cut around £189,000 and £74,000 profit respectively. Art exhibitions encourage repeat visits, and Flanaghan hopes numbers will also increase following the miniseries of Ken Follett’s bestselling novel, Pillars of the Earth, which tells the story of England’s first Gothic cathedral in the fictional Kingsbridge and bears a close resemblance to Salisbury.

Salisbury is fortunate to have a healthy 500-600 core congregation; it’s a small city, and people feel close to their cathedral. So, is there friction between its moral Christian purpose and the imperatives of a modern business?

“Of course there is a balance and tension,” the dean says with twinkly good humor. “I’m a priest as well as a chief executive, so I live out that tension. But we don’t do a split: here is the filthy lucre of business and over here is the pure zone of prayer. Our fundamental belief is that God is the lord sovereign of everything we get up to and we shouldn’t underestimate the power of encounter and engagement; we are here to change people’s lives. I enjoy that we sometimes take risks; occasionally we might step over the line, but not often.

Visiting

Salisbury Cathedral is 90 miles southwest of London. There are frequent train services from London and Bath, and it’s a 10-minute walk from the station to the cathedral. Tel. 01722 555120;

www.salisburycathedral.org.uk

“We have this tremendous responsibility, and people are amazed that we run everything and our capital budgets without central funding, either from the Church of England or the Government,” Osborne adds. “That gives us independence and makes us sort out our priorities.”

Indeed, there has been some radical stock taking of late, and I dropped in on development director Claire House-Norman in the Chapter Office to find out more. Fundraising at the cathedral got serious after a survey in the 1980s revealed the whole building was in need of repair and conservation—the last significant work had been carried out in the 19th century. A successful appeal raised £7 million, largely from locals, for the most pressing concerns, including the spire that was at risk of collapse “over the next 100 years.”

Since 1986 a Major Repair Programme has been methodically progressing around the cathedral; 60 percent of work has been completed and £22 million spent; there’s another £12.5 million required to see things through, hopefully finishing in 2018.

The Development Office was established in 2008 to meet increasing fund-raising challenges. In addition to fighting for resources from grant-giving bodies like English Heritage and The Wolfson Foundation, House-Norman and her team of two seek to build relationships with individual donors.

[caption id="CathedralsinCrisis_img6" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

COURTESY OF SALISBURY CATHEDRAL UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED

“Previously about 31 percent of our money for repairs has come from English Heritage and The Wolfson Foundation, 21 percent from cathedral reserves, 37 percent has come from the Spire Appeal and 11 percent from the Cathedral Friends,” House-Norman explains. The discontinued English Heritage scheme for cathedrals will be missed, although a replacement worth £500,000 spread between all cathedrals has been launched. House-Norman has applied for £60,000 for window repairs.

She is a passionate advocate. “Our cathedral isn’t just this big, pointy thing. We do so much work, like education and social justice programs for the homeless and drugs users.” The cathedral hosts over 1,200 services a year, maintains flourishing boys’ and girls’ choirs, stages concerts, runs an education center, school holiday activities and much more. The big pointy thing may be the physical focus of the repair program, but it’s the human reality it embraces that is, well, the point, too.

Since August 2008 the development department has raised £2.2 million. An anonymous local donor pledged nearly £1 million for the restoration of the Chapter House and the grisaille-painted Hemming Window of 1895: the Chapter House project had been scheduled for 2015-17 and was hastily brought forward to “follow the money.” A Canadian horticulturist who has never even visited the cathedral gave £100,000 to relandscape the Cloister Garth. Another anonymous donor gave £200,000 for three years’ running costs of the cathedral’s social justice program.

Other Cathedrals in Peril

Lincoln Cathedral www.lincolncathedral.com One of Europe’s finest medieval buildings has a works program over the next 10 years costed at £16.5 million. In 2011, it moves on to the sublimely carved West Front with its frieze of Old Testament scenes. An initial £2.5 million Turrets Restoration Campaign has already been launched to tackle weathering of the early 13th-century turrets that bookend the stunning façade. You can adopt a stone on the West Front for £25. Dragon carvings, organ pipes, books, stained glass and more can also be sponsored.

[caption id="CathedralsinCrisis_img7" align="alignleft" width="302"]

HYPERMANIA2/123RF

Canterbury Cathedral www.canterbury-cathedral.org

The Mother Church of the Anglican Communion has an average income of £8.7 million from its own resources and donations. Around £4 million each year is spent on repair and conservation work. The Canterbury Gift Appeal has raised £10.5 million of a £50 million target, and projects include: £multimillion repairs to 15th-century Bell Harry Tower, releading the roof (more than 3,000 tiles), cleaning and restoring the stained glass (including more than 400 square meters of medieval work), enhancing visitor facilities and helping to train five craft apprentices.

[caption id="CathedralsinCrisis_img8" align="alignleft" width="316"]

DANA HUNTLEY

York Minster www.yorkminster.org

In the 1960s and 1970s when the minster’s central tower risked collapse, £2 million was raised, and in 1984 when the south transept roof burned down, money poured in, not least from the insurance company. Spectacular disasters are good for fundraising, but there’s plenty of day-to-day stuff, too. Masons and carvers at the minster are currently challenged with replacing at least 2,500 stones on the East Front, for example. You can sponsor a stone for £600, and group visitors can book tours of the stoneyard and ascend the East Front in a hoist to inspect ongoing work.

[caption id="CathedralsinCrisis_img9" align="alignleft" width="306"]

LANSERA/123RF

Equally breathtaking: most benefactors are content with a simple letter of thanks, although the cathedral willingly offers tokens such as private tours or a bespoke carved grotesque to take home.

It’s a striking thought that the major repair program will have taken some 30 years to complete, while the cathedral’s medieval builders were more or less done in just 38: today’s bureaucracy means it takes a year of surveying and form filling before any artisan gets to start a project. Another challenge is to find or train craftsmen with the right skills. Salisbury’s glazing and stonemasonry departments operate apprenticeships, but Peter Edds, head of Buildings and Estate, has taken development to a new level by helping to establish the Cathedrals’ Workshop Fellowship.

“Only eight cathedrals now have workshops that employ any significant number of craftsmen, and we were unhappy with available training for masons,” explains Edds, who has previously worked at Windsor Castle and other notable venues. “So we set up a foundation degree at the University of Gloucestershire, with an apprentice from each of the eight cathedrals on it.” In time, the course may be opened up to other organizations.

[caption id="CathedralsinCrisis_img10" align="aligncenter" width="789"]

SPIX

[caption id="CathedralsinCrisis_img11" align="aligncenter" width="275"]

SPIX

[caption id="CathedralsinCrisis_img12" align="aligncenter" width="773"]

SPIX

‘IT’S A STRIKING THOUGHT THAT THE MAJOR REPAIR PROGRAM WILL HAVE TAKEN SOME 30YEARS TO COMPLETE’

[caption id="CathedralsinCrisis_img13" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

COURTESY OF SALISBURY CATHEDRAL UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED

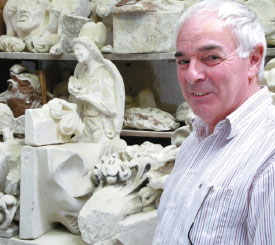

So I tour the Works Department, which dates from 1220 when the cathedral was first built from Chilmark and Purbeck stone. Sixty-seven statues adorn the West Front, gargoyles peer and leer and there’s been a lot of weathering through the centuries. Diagrams on the workshop wall highlight each single stone that needs attention, either to be conserved in situ or removed and replaced.

“We get Chilmark stone from a quarry 12 miles away, from the same bed as the original stone came from,” General Manager Ted Hillier says. Mould cutters create exact templates for each piece to be replaced, a sawyer cuts the stone and then masons shape and refine it. No two pieces are the same, because the medieval masons worked without formal plans, sometimes leading to interesting “bodges”: unusual asymmetries here, an angel hunched down to squash into a recess there.

Head stonemason Chris Sampson breezes in and opines that Salisbury’s medieval originators probably didn’t take a long-term view. “Cathedral building was a pioneering exercise; they made things up as they went along and would have expected their work to be superseded by something better.”

Well, 752 years on Salisbury Cathedral is still going strong, and its architecture is widely admired. Mighty challenges lie ahead, but there’s a magnificent bunch of friendly, optimistic, determined people here to tackle them.

Comments