[caption id="DirePredictionsthatHalleysCometwillPoisontheWorldgoUnfulfilled_img1" align="aligncenter" width="232"]

© BETTMANN CORBIS

“That comet is going to hit the earth!”

So said one of the two men who got into the train and settled down.

“Ah!” said the older man.

“They do say that it is made of gas, that comet. We shan’t blow up, shall us? …”

—IN THE DAYS OF THE COMET,

by H.G. Wells

IT’S SAID THAT A LITTLE BIT OF knowledge is a dangerous thing. But a little knowledge bolstered by a wealth of imagination can be downright terrifying.

In the late 17th century, the astronomer Edmund Halley provided the academic community of England with a little knowledge when he worked out, mathematically, that the comets visible over English skies in the years 1066, 1531, 1607, and again in 1682 were all appearances of the same celestial object. What’s more, based on careful measurements of the comet’s orbit, Halley confidently predicted that it would return yet again every 76 years. Sure enough, in 1758, although Halley did not live to witness it, his comet returned, thus proving his hypothesis.

[caption id="DirePredictionsthatHalleysCometwillPoisontheWorldgoUnfulfilled_img2" align="aligncenter" width="463"]

© BETTMANN CORBIS

You might think that by the time the comet had made two more circuits of the sun, its regular visits to the neighbourhood of earth would have become rather routine. But during the 76 years that preceded its expected reappearance in 1910, scientific advances enabled astronomers to determine the comet’s composition. The object that was streaking towards earth, they discovered, was made partly of cyanogen gas, a deadly poison. To scientists, this discovery may have satisfied a purely academic curiosity but had little if any practical consequence. Those in the know understood that the amount of cyanogen in the comet’s tail (which the earth would pass through) is so fabulously small that it poses no conceivable threat to anyone.

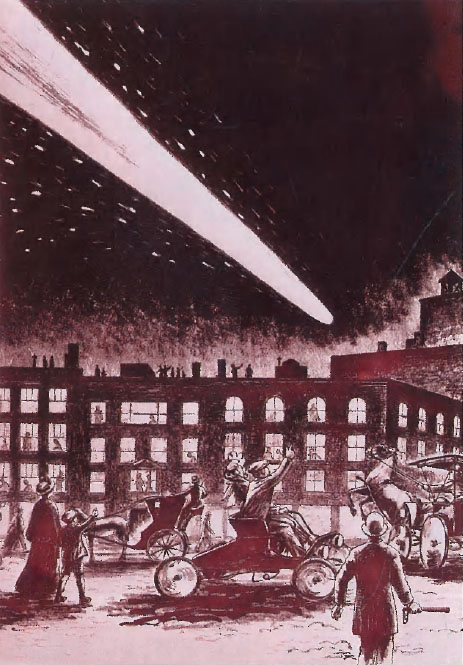

But many in the popular press and the public at large reacted to the news by predicting apocalyptic results from the earth’s encounter with the comet. Opportunistic entrepreneurs helped spread the panic by selling “comet pills” containing who-knows-what, which they claimed would protect their customers from the deleterious effects of cyanogen. As “Doomsday” approached, fatalists took to their roofs for a better view of the comet and to huddle together and await the end.

In Britain, though, Halley’s Comet was not visible until after it had already passed by. Those who had stocked up on comet pills probably felt both relief and embarrassment as they read in The Manchester Guardian on 24th May that: “Last night the long-looked-for comet was visible at last to us in the north. In Manchester itself the haze which the smokestacks of industry gather over the city hid it from view, but out in the country in parts of Lancashire and Cheshire the sky was beautifully clear, and the brilliance of a moon reaching its full was not enough to blot it from sight…. Its unfamiliarity made it easy for the eye to light upon it, but it was very dim and distant, and there was nothing but a faint luminosity about the edge to suggest to the naked eye the tail through which our planet had gone swimming in the past week…”

But the comet did have one lasting effect. While fears had run wild over the possibility that it might suffocate the human race in deadly fumes, one English writer imagined a different outcome. In the year prior to the comet’s rendezvous with earth, novelist H.G. Wells was inspired to write an optimistic vision of a Utopian future, which he titled In the Days of the Comet. Inspired by the timely speculation about comet-gas, Wells’ story—even less plausible than the claims of the comet-pill hawkers—tells how the human race is changed for the better by the magical properties of comet gas that transform everyone on the planet from selfish, violent brutes in-to enlightened paragons of virtue.

The England of Wells’ story teeters on the verge of a socialist revolution, as well as the brink of war with Germany—the one prognostication in this whole affair, seemingly, that proved accurate. The novel’s flawed hero, Willie Leadford, spurned by his love, Nettie Stuart, buys a gun and hunts her and her new lover down with murderous intent. All seem headed for ruin until green comet gas envelops them and puts them to sleep. Upon reawakening, class distinctions seem like a silly bygone notion, politicians try in vain to remember why their nations couldn’t get along, and Willie and Lettie laugh at the outdated Victorian morality that frowned on polygamy.

Of course, it is highly doubtful that anyone anticipated such an outcome from earth’s encounter with Halley’s Comet. Presumably, they were quite satisfied with simply not being poisoned.

COMET MAN

Learn about Edmund Halley, “The Comet Man,” by visiting the History Online page at BritishHeritage.com.

Comments