[caption id="EggsNorwegianEverydayEphemeraandaBitofOldLondonBridge_img1" align="aligncenter" width="180"]

MUCH OF THE STUFF I’ve been looking at this month has been about preserving things after most people would think they’d stopped being useful. The subject has been at the forefront of my mind for a couple of reasons—first an annoyingly short-lived exhibition at the Guildhall Art Gallery on “Lost London”—which looked at bits and pieces of the city that have ended up all over the world—and secondly a collection of London photographs from 1937, A Camera on Unknown London by one E.O. Hoppé, that I found in a charity book sale.

[caption id="EggsNorwegianEverydayEphemeraandaBitofOldLondonBridge_img2" align="aligncenter" width="245"]

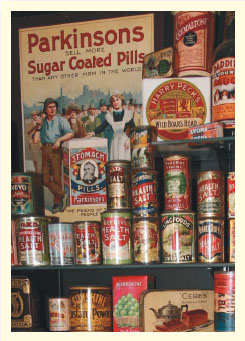

COURTESY OF THE MUSEUM OF BRANDS, PACKAGINING AND ADVERTISING

The book got me wondering how many of the curiosities depicted still existed after the combined efforts of Hitler and greedy developers. The resulting search is an ongoing project, and so far with mixed results, which I hope to bring you over the coming months. But while it’s true that developers still haven’t stopped tearing down important old buildings, there remain people around who are prepared to look for beauty in the smallest things.

Back in 1963, a teenaged Robert Opie bought a packet of chocolate Munchies. When he had finished scoffing the sweets, he made a momentous decision—not to throw away the wrapper. I can only imagine his parents’ despair as, over the next 40-odd years, Opie not only refused to throw anything away, but started collecting other people’s rubbish, too, hoarding it in the garden shed.

By 1975, he’d accrued enough chocolate wrappers, crisp bags, biscuit boxes, Coke cans, shampoo bottles and baked bean tins to present a small display in the Victoria and Albert Museum. Today, the Robert Opie Collection of commercial packaging runs to several warehouses, and a series of best-selling books.

THE TINY BUT exquisitely formed Museum of Brands, Packaging and Advertising can only ever house a minute percentage of the collection at any one time. So Opie personally oversees a rolling exhibition of some of the most beautifully displayed trash in London. Hidden away down a mews in Notting Hill, the museum is a deeply satisfying meander through British history from Victorian times to the present day, via the everyday ephemera that most folk throw away. I took my parents and we spent an afternoon ooh-ing and aah-ing at tins of chocolate from World War 1 trenches, packets of starch from Blitz-hit London and staggeringly beautiful biscuit tins in the shapes of sundials, lighthouses and gypsy caravans from the 1920s. All are presented with the kind of love only a true British eccentric can lavish on an obsession.

CRYSTAL PALACE suddenly became extremely fashionable in the 19th century when, after the Great Exhibition of 1851, the government was looking for a permanent home for the gigantic greenhouse of an exhibition hall designed for the event by Sir Joseph Paxton. It was finally placed high on a hill in leafy Sydenham and turned into a tourist attraction. The park was landscaped with the usual Victorian accompaniments—think cast iron, gaudy flowerbeds and bandstands—but it also boasted a completely unique curiosity.

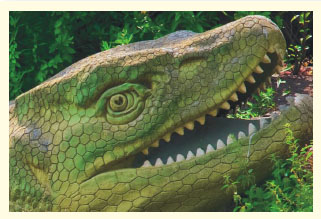

The Victorians were great naturalists, and there was a veritable craze for palaeontology. Dotted around the landscaped lakes, life-size dinosaurs still lurk among Crystal Palace’s greenery. Created in 1854, they were the first-ever life-size representations of dinosaurs, and they’re probably still the only Grade 1 listed dinosaurs in the world.

Of course, they’re completely wrong— gaps in knowledge were made up for with ample amounts of imagination—but they are all the more terrifying for that. Trees and shrubs have grown around them, making them difficult to spot and even as an adult, I felt the odd shudder as an ichthyosaur crawled onto a bank, or a megalosaurus stood on a promontary above me. They’re realistic—and at the same time really, really fake—a heady combination. I found myself wishing I could have attended the famous New Year’s Eve banquet of 1853, held inside the half-finished iguanadon.

[caption id="EggsNorwegianEverydayEphemeraandaBitofOldLondonBridge_img3" align="aligncenter" width="321"]

VISITLONDONIMAGES/BRITAINONVIEW/PAWEL LIBERA

DINO[/caption]

Sadly the Crystal Palace itself burned down in 1936. Its foundations remain a ghostly Mecca for architecture buffs, who climb the massive steps to pace out its still-visible footprint. But the rest of us just go for the staggering view, which stretches out across London.

CINEMA PRESS PREVIEWS always seem to take place at the most inappropriate time for the film concerned. So one sunny Sunday morning saw me in Leicester Square with a bunch of pale-faced, eyelinered teenagers in top hats and cloaks attending the preview of a vampire movie.

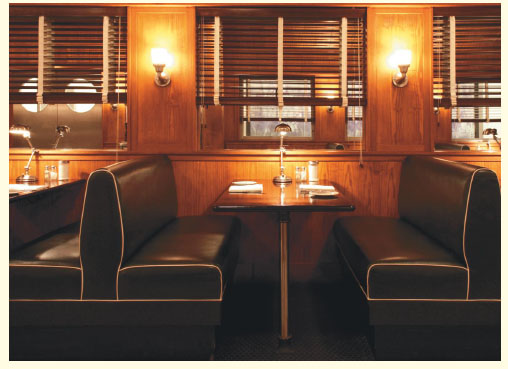

I won’t sport with your intelligence by describing the film—but the place we ended up afterward was a bit of a revelation. The Automat is one of those little tucked-away brasseries, right in the heart of Mayfair, that it’s always good to know about. What I love about it is its style—a cross between a classic American diner and a train.

The tiny Dover Street entrance opening into a cozy little café area is deceptive. Narrow, galley-like rooms, going way back into the building, are designed to bring to mind a wagon—but for me they are more like 1950s railway compartments. Either way, necessity is turned to a virtue.

THIS MONTH’S CONTACTS

THE MUSEUM OF BRANDS, PACKAGING AND ADVERTISING, at 2 Colville Mews, Lonsdale Road, Notting Hill, London, W11 2AR.

www.museumofbrands.com

CRYSTAL PALACE PARK is in South London—the nearest train station is Crystal Palace.

THE AUTOMAT, 33 Dover Street, Mayfair London W1S 4NF |Tel: 020 7499 3033 www.automat-london.com

THE LONDON BRIDGE SHELTER is in the grounds of Guys Hospital, Great Maze Pond, London SE1 9RT.

[caption id="EggsNorwegianEverydayEphemeraandaBitofOldLondonBridge_img4" align="aligncenter" width="508"]

COURTESY OF THE AUTOMAT

THE AUTOMAT[/caption]

Wood-panelled walls with curved ceilings, Venetian-blinded “windows,” art deco uplighters and bench seats complete the look, before the place opens out first into a white-tiled modern bar, then a larger informal dining area and funky exposed kitchen.

We had the classic (and extremely popular— the place was heaving) Sunday brunch—buttermilk pancakes, Po’ Boys, burgers and Eggs Benedict. Being an ignorant Brit, I had to ask what an Eggs Norwegian was—apparently it’s like a traditional Eggs Benedict, but with salmon. It was fluffy and succulent, but with that slightly acidic tang that makes brunch worthwhile.

I WAS KEEN TO GET CRACKING ON A Camera on Unknown London. I had always assumed that when the medieval London Bridge was demolished to make way for the famous Rennie design (now residing in Arizona, of course) all the original bridge was destroyed. But E.O. Hoppé told me one of the little arched stone rain canopies that sheltered pedestrians as they crossed had been saved. He directed me to the grounds of Guys Hospital, just round the corner from London Bridge station.

The hospital’s majestic 18th-century edifice hides fascinating little gardens with trees, statues and memorials I never knew existed. And there, among the daffodils and tulips in an inner courtyard, stood that little stone arch, still providing shelter; albeit more for medical students than travelers these days. Oh—and a seated statue of John Keats, who studied to become an apothecary at Guys before finding fame as a poet.

So—an auspicious start for my 1937 book-quest. It wasn’t all to be such plain sailing. But that’s for another day. Next time I’ll be searching out some more little-known delights from A Camera on Unknown London, heading out east to find London’s last lighthouse and visiting what must be the only 19th-century operating theater in the tower of a church.

Comments