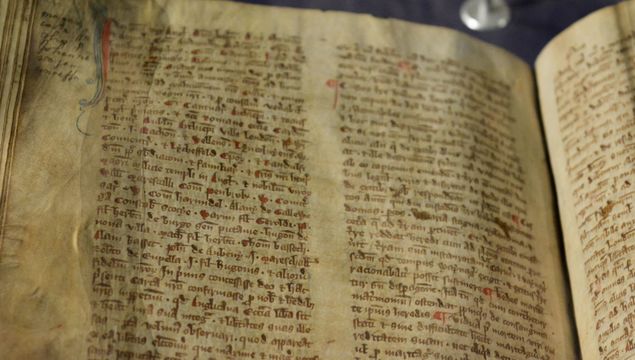

A copy of the Magna Carta can be seen in Christ Church, Dublin, Ireland.Getty

It formed the basis for America's Bill of Rights but what is the Magna Carta, and how did the Great Charter come to be? Perhaps the most important document produced in the British Isles the Magna Carta symbolized within their compact script: fundamental principles of democracy and human rights.

The British Library's softly illuminated Treasures Gallery contains many texts that mark milestones in man’s intellectual history, including an original Gutenberg Bible and Leonardo da Vinci’s scientific notebooks. The intensely illuminated Lindisfarne Gospels and Baybar’s Qu’ran are items of radiant beauty that starkly contrast with a couple of dull parchments of indeterminate hue. These parchments are two copies of the Magna Carta. There are four extant copies of Magna Carta - two in this gallery and one each in Lincoln and Salisbury cathedrals.

Read more

These two single sheets of vellum, about the size of A3 paper, are displayed below the bulletproof glass and receive reverential attention from visitors of numerous nationalities. The feudal documents, written by monastic hands in legal Latin, are famous for what is believed to be symbolized within their compact script: fundamental principles of democracy and human rights.

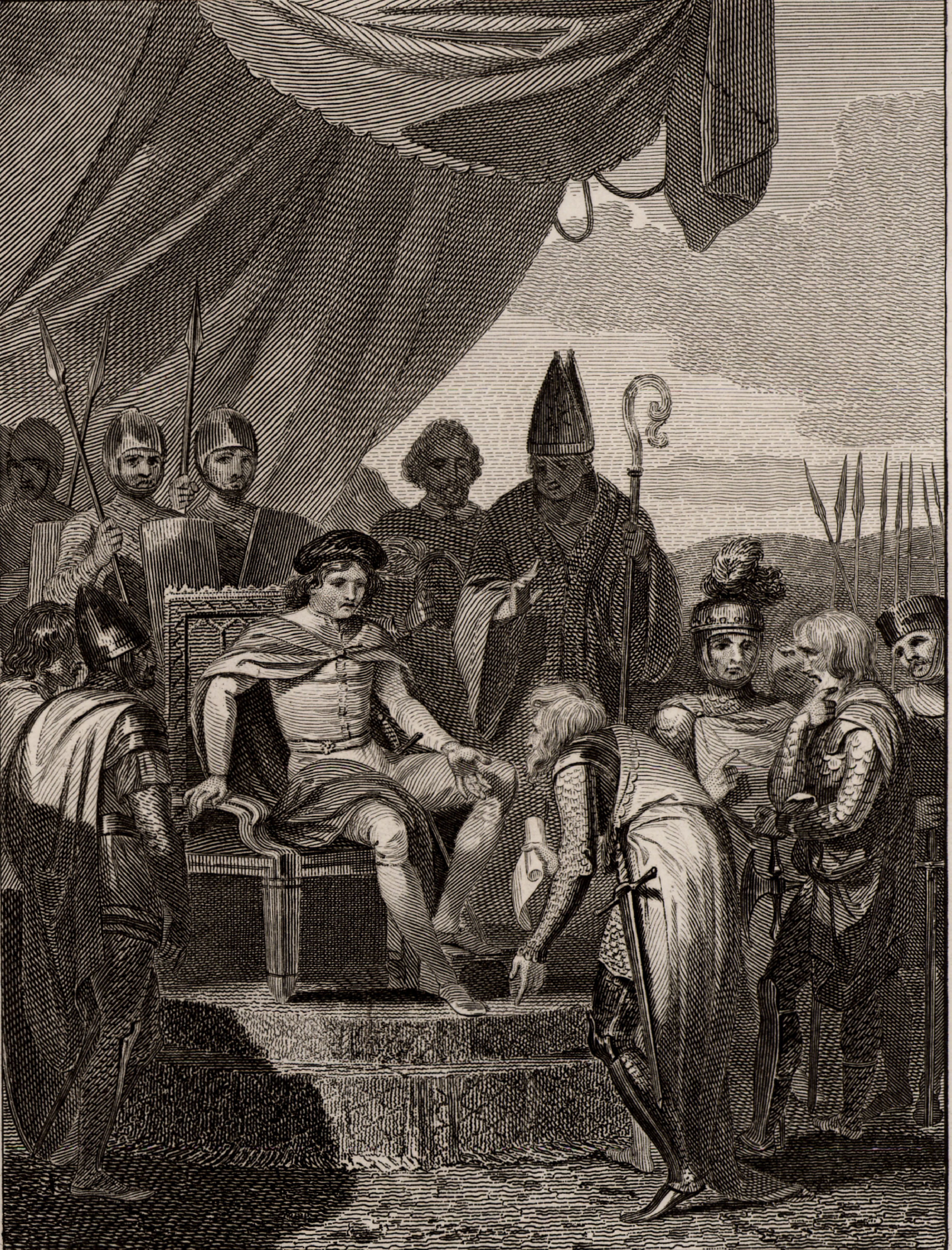

Magna Carta presented to King John of England

This perception is confirmed by frequent references to Magna Carta as being instrumental in formulating the unwritten constitution of the United Kingdom; the Declaration of Independence, Constitution and Bill of Rights of the United States; and the constitutions of modern Germany and Japan. Technically, those perceptions are not entirely correct.

What is the Magna Carta?

Signed by England’s King John in 1215, the charter does not enshrine any nation’s democratic and legal rights. Magna Carta is not a document outlining a model for democratic government; to feudal nobility, notions of democracy would have been very alien. Rather, it was a document created through an act of rebellion that provided a contemporary solution to a political crisis regarding feudal governance, taxation, justice and royal authority that successive monarchs had abused. Still, Magna Carta does contain some robust clauses that in succeeding centuries evolved into keystone principles of democratic government and human rights.

How did the Magna Carta come to be?

The trail following Magna Carta's conception, survival, and evolution into an icon of freedom is still pertinent. Feudal kingship depended, in part, on financial largess. King John succeeded to the English throne and overlordship of substantial French territories in 1199. The England he inherited was economically weakened by nearly a century of civil war and had been financially stripped by his brother Richard, who had used his English estates to bankroll his foreign adventures. By 1205, through political and military incompetence, John had lost most of his French territories. Thus a priority of his reign was to retake those lands - an expensive undertaking that would have to be funded by his English barons.

King John was politically inept. Like his father and brother, he was a ruthless murderer and rapist. Unlike them, he was unskillful in his avaricious pursuit of power. He failed to understand the value of alliances, friendships, and trust, all of which he consistently abused. He firmly believed it was his divine right to raise money however he wished. John’s income was generated through a complex system of land tenure and fees that were theoretically constrained by custom. Principally, income came from fees paid by sheriffs, determination of land inheritance, granting of privileges to economically successful towns such as London and Lynn, and scutage; a fee paid by barons to finance military campaigns.

Autumn day at Salisbury Cathedral, England

John in the first decade of his reign increasingly pressed his sheriffs for higher fees. He perverted the law as it pertained to land tenure and inheritance. Barons became increasingly upset at the frequency of scutage, an unprecedented 11 times in 16 years. His continued military failures made scutage particularly irksome.

King John provokes Pope Innocent III and the barons

King John provoked Pope Innocent III’s wrath when he opposed the appointment of Cardinal Stephen Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury. In the ensuing row, England was placed under a papal indict, and John was excommunicated - initially a lucrative predicament as John garnered the profits from the church’s substantial estates.

John’s continued imprudent levying of taxes, unscrupulous disregard for custom and avaricious dispensation of justice eroded the nobility’s respect for their sovereign. By 1213 John’s political situation was desperate. He made peace with the church and took the Crusader’s oath, cynical but successful maneuverings to regain papal support.

The barons’ endeavors to address John’s inappropriate application of power meant the nobility and crown would come into conflict. Neither the barons nor John wanted a civil war, but both sides initiated military posturing. The rebel nobles captured London in May 1215. Unable to mount a serious military challenge, John agreed to meet the contentious barons near Windsor in June, at the meadow of Runnymede.

King John agrees to the Magna Carta

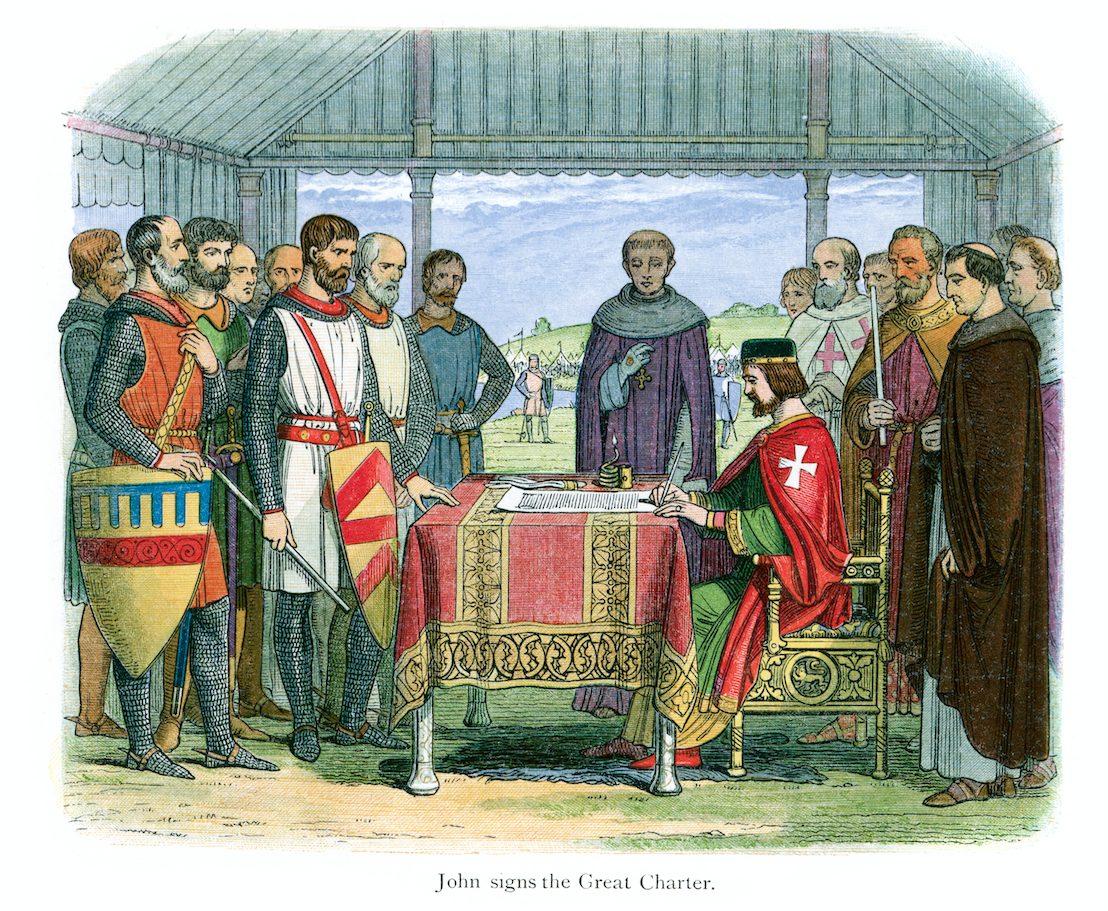

For several days, both sides’ representatives haggled over an agreement. The barons had arrived with a charter, the Articles of the Barons, which contained 43 clauses. On June 15, 1215, somewhere on the meadows of Runnymede, John reluctantly assented to the charter, which now contained 63 clauses, and became known as Magna Carta - The Great Charter.

John’s seal was not applied to a single vellum document, but to several copies a few days later.

How many copies were made is unknown, but probably enough for each county sheriff and all the bishops? The different writing styles indicate different people redacted them, which explains the minor variations in wording between copies.

King John signing the Magna Carta

The barons, through the threat of rebellion, had apparently reestablished their rights, but John was reluctant to have his royal authority constrained by a mere document. He immediately petitioned his now papal ally to denounce Magna Carta, and in late August, a papal bull declared Magna Carta illegal.

John’s duplicity angered the barons. Before Runnymede they had not wanted to supplant him; now they did. They chose Prince Louis of France as his replacement. During the winter of 1215-16, both sides prepared for war. John successfully besieged Rochester, while the rebels gained control of much of East Anglia.

To counter the threat in East Anglia, John went to Lynn (today’s King’s Lynn) and suffered a series of disasters. Traveling from Lynn to Swineshead Abbey, his treasure was purportedly lost in the marshes of the Wash. More likely it was purloined. At Swineshead, John became ill, and he died a few days later at Newark Castle. Some historians believe he was poisoned.

The Magna Carta is reissued

With John gone, the barons changed their kingly choice from Prince Louis to Henry, John’s young son. Henry’s guardian, William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, insisted on reissuing Magna Carta as a means to assure the rebellious barons that they had written finis to John’s despotic style of government.

In 1297 Edward I placed it on the first statute roll (records of English Law), so confirming Magna Carta’s significance: A group of rebellious barons had curtailed the excesses of a tyrant king.

Vintage engraving of Magna Carta Island an island in the River Thames in England, on the reach above Bell Weir Lock. It is in Berkshire across the river from the water-meadows at Runnymede. The island is one of several contenders for being the place where, in 1215, King John sealed the Magna Carta.

Magna Carta’s importance lies within its essence: the curtailment, by a written document, of a despot who was levying extortionate taxes on his nobles and ignoring proper legal restraints. The whole document, not individual clauses, assumes that the concept of good governance exists and is achievable, and that all persons are subject to the law, including the king.

The Magna Carta is changed

The major mutation of associations with Magna Carta occurred in the 17th and 18th centuries. During the reigns of James I and Charles I, the parliamentarian Edward Coke successfully argued that Magna Carta made the monarch subject to the law like everyone else. This reinterpretation stimulated a series of legal debates referring to ancestral rights contained within Magna Carta. Such debates placed the Magna Carta into common law and national consciousness.

These debates were appreciated by such American colonists as John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Benjamin Franklin, who then took the spirit of Magna Carta to frame the Declaration of Independence.

Since 1776 the essence of Magna Carta’s ideals has been invoked again and again, including in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which expresses it this way: “Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person; no one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile; everyone is entitled in full equality to a fair and public hearing in the determination of his rights and obligations and of any criminal charge against him, and no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property, and everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression.”

It is these ideas that resonate with visitors to the British Library, to Lincoln and Salisbury cathedrals, and to the US Capitol Rotunda in Washington, D.C., where a fine gold-etched replica of Magna Carta has been displayed since America’s bicentennial in 1976.

At Runnymede, in an oak tree glade, a stylized Greek temple erected by the American Bar Association simply summarizes the spirit of Magna Carta thus: “To Commemorate Magna Carta, Symbol of Freedom Under Law.” Nearby a plaque quotes the forceful British judicial figure Lord Denning’s summary of Magna Carta: “…the greatest constitutional document of all time—the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary rule of the despot.”

The exact location where John applied his seal to Magna Carta is not known, but that act has provided a legal legacy that has guided British law for eight centuries and been influential in legislative and judicial systems around the world.

* Originally published in July 2016.

Comments