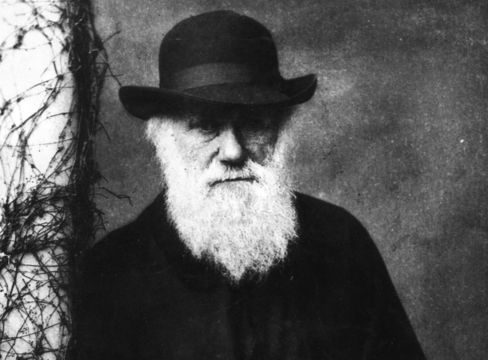

Author of On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin.Getty

A look at the life and works of Darwin, the English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, best known for his contributions to the science of evolution.

It was over 160 years ago, 18 miles from London in a comfortable, rambling house near the village of Downe, that one of the world’s preeminent scientists put his theories into written form. Although his book never mentioned evolution—the author preferred the term “natural selection”—and no ape raised a hairy, contentious head, On the Origin of Species launched a firestorm of controversy that continues today.

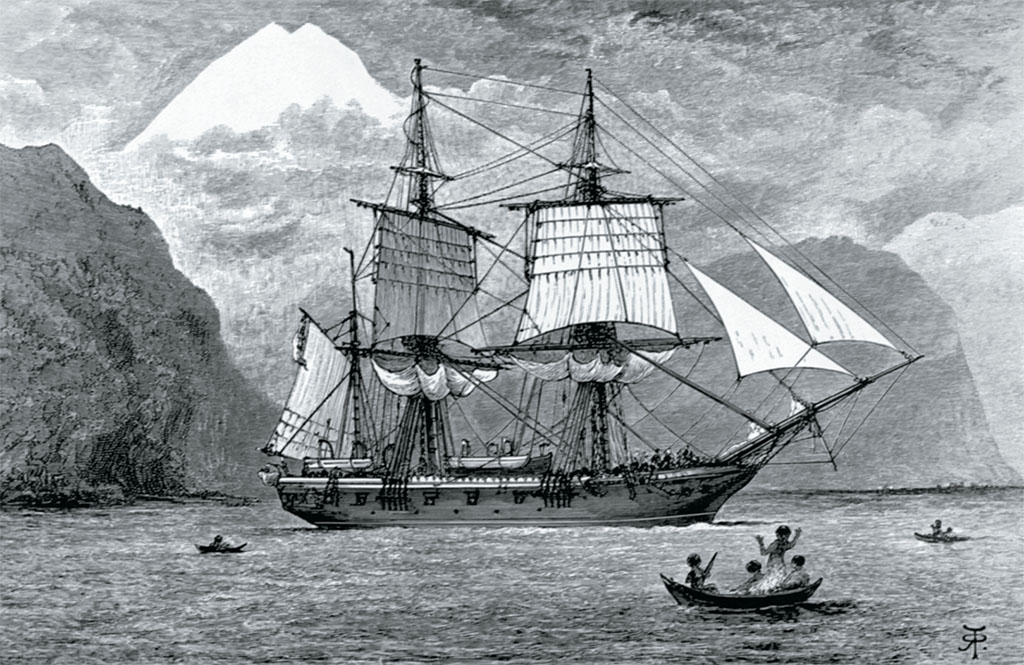

Despite the criticism, Darwin’s fame spread and his works were reprinted. This 1890 illustration depicts HMS Beagle carrying Charles Darwin’s expedition into the dangerous Straits of Magellan with Mt. Sarmiento in the background. Via: BETTMAN/CORBIS

Charles Darwin was born in Shrewsbury in on Feb 12, 1809. His grandfathers, both dead before he was born, were scientist and inventor Dr. Erasmus Darwin and Josiah Wedgwood of pottery fame. Erasmus Darwin wrote a book comprising all botanic knowledge in poetic couplets and had tentative theories about evolution. Wedgwood was a master potter who developed new types of earthenware. Poor health, suicide, mental illness, depression, and early deaths were recurring themes through the Darwin and Wedgwood generations.

Charles’ father, Dr. Robert Waring Darwin, was a large, powerful man who dominated conversations and his children’s lives. His mother, Susannah Wedgwood, a gentle, quiet woman who shared her husband’s interests in botany and zoology, died when Charles was 8.

One of history’s foremost scientists never took a degree in science or anything else. He spent his childhood reading Shakespeare and poetry, collecting fossils, rocks, and shells and studying insects and birds.

His father forced him to undergo two years of medical studies at the University of Edinburgh, but he found his medical lectures “something awful to remember” and spent much of this time learning taxidermy, attending geology lectures and collecting marine specimens. He joined several undergraduate societies where he read his own papers and first heard about that revolutionary theory, evolution. After viewing two botched surgeries performed without anesthetic—one on a child—he fled the operating theater and the school.

Dr. Darwin next decided his son would make a suitable country parson, and sent him to Christ’s College, Cambridge, for two years. Although a devout Bible believer at this point, Darwin seems to have spent less time studying theology and more on hunting both foxes and beetles and playing cards with “dissipated low-minded young men.” But he also forged friendships with senior members of the university staff, who apparently saw something in this young man who scamped his studies and collected mosses and rocks.

“Looking back, I infer there must have been something in me a little superior to the common run of youth, otherwise the above-mentioned men, so much older than me and higher in an academic position, would never have allowed me to associate with them,” Darwin later wrote.

One of them, botany professor John Stevens Henslow, became a close friend and a defining influence in his life. He recommended young Darwin for the position of naturalist on the Royal Navy vessel Beagle, commissioned to make a scientific survey of the coasts of South America. Despite his father’s objections, and after many delays, Darwin set forth on “by far the most important event in my life” on December 10, 1831.

Down House lies in Downe, 15 miles south of central London, in the care of English Heritage. Find visiting details at www.english-heritage.org.uk. Via: BRITAINONVIEW/IAN SHAW

The voyage was scheduled to last two years but extended to almost five. Although Darwin was originally hired as a geologist, he collected botanical specimens as well, sending cases of them back to Henslow along with detailed field notes. He traveled throughout South America, South Africa, Australia, the Falklands, and a number of small Oceanic islands, wondering at the diversity of plant and animal life, collecting fossils of giant sloths and extinct giant armadillos. He saw miniature foxes, wolves unlike the European variety, flightless birds and beetles, and that puzzling creature the duck-billed platypus.

He trolled for plankton, whose varied beauty served no apparent purpose. He rode, hiked, hunted, endured bad weather and mosquito bites, and experienced good health except for seasickness until September 1834, when he fell deathly ill in Chile. He was probably a victim of Changas’ disease, caused by exposure to armadillos, which he studied and occasionally ate, or bites from the Benchuca, “the great black bug of the Pampas.” It was the beginning of a life of chronic illness.

Beagle arrived in the archipelago of the Galapagos in September 1835. There Darwin observed the varied beaks and body structure of the native finches (later called Darwin’s finches) and mockingbirds, which were obviously adapted to different biological niches. He noted the giant tortoises, which the sailors happily collected for food, and three varieties of turtle. He learned that among the five islands he visited, some had plants that others did not, although their climate and terrain were the same. It all caused him to question creationism.

Many of the famous botanist’s effects are on display at Down House, including his hat and personal items from his historic voyage on Beagle. Via: ROGER PASCHKE

“The land is one great, wild, untidy, luxuriant hothouse, which nature made for her menagerie,” he wrote exuberantly. But the popular notion that the theory of natural selection dawned on him overnight in the Galapagos is false. It was only when he had spent years poring over his notes and specimens that he put his ideas into the final form.

Back home in 1836, Darwin began the daunting task of organizing his materials, enlisting friends and colleagues, and parceling out responsibility for large fossil bones, reptiles, birds, and the like. His father, having decided the work was worthwhile, made him financially independent. Darwin joined a circle of scientists as a respected colleague.

In January 1839 he married his cousin Emma Wedgwood, and in 1842 settled at Down House, a modest home where his many children could romp, and with a garden where he grew fruit and vegetables and tried out various experiments. “Its chief merit is its extreme rurality,” he wrote.

Today the house looks as though the occupants had just stepped out, perhaps for a stroll down the “sand walk” where Darwin walked and meditated almost every day, or to gather fruit from the ancient mulberry tree. The dining room table is set inevitably with Wedgwood china, ready to be handed round by liveried menservants. Darwin, who was a magistrate, sometimes held court here. In the stair cupboard, sports equipment shares space with a copy of his last revision of Origin wrapped and ready to mail after his death. Emma’s needlework rests on a chair.

Darwin’s study, intact even to the original wallpaper, is littered with specimens, scientific equipment, and his fox terrier Polly’s basket. He could retire to a discrete lavatory behind a screen to be sick, which happened often.

His snuff jar sits on the sideboard, under a water-color of Beagle. Emma’s Broadwood piano, the backgammon board on which he played two games every night and the billiard table where he challenged his butler complete the furnishings. In the upstairs museum is a model of Beagle, the Panama hat that shielded him from the tropic sun during his quest, a family tree, a lock of Emma’s (gray) hair, and his family’s childish souvenirs. Sources as varied as John Scopes, John Paul II, and Dolly the sheep weigh in. Darwin in bronze sits in a chair and surveys it all.

Charles Darwin is commemorated as Shrewsbury’s most celebrated son in this statue outside the town library. Via: BRITAINONVIEW

Darwin spent the rest of his life at Down House. He’d become a chronic invalid, suffering a host of ills including nausea, fainting, panic attacks, depression, hysterical crying, and boils, most of which had plagued him for years and none of which ever abated completely. Whether they were caused by psychosomatic sources, heredity, Changas’ disease, or a combination of them all is still debated. Work kept him from brooding about his health.

He had already published his trip journal and a travelogue about his voyage, plus books on coral reefs, volcanic islands, and South American geology. At Down, he wrote books on beetles and volcanic islands. He spent eight years studying the barnacles he had brought back on Beagle. (“Where does your father do his barnacles?” his 8-year-old son asked a playmate.) He bred pigeons, placed earthworms on the piano to see whether they reacted to the music and dissected assorted animals.

It wasn’t until November 1859 that On the Origin of Species saw print, and then only because others were already publishing similar ideas. He had intended to write an “abstract” for a scientific journal, but the result was a lengthy book. It stressed “modification” and “co-adaptation” and occasionally gave “the Creator” credit for setting the whole process in motion.

The result was a flood of criticism that did nothing for his health. While some friends and colleagues supported his ideas, others were vitriolic in their opposition. One clergyman dubbed him “the most dangerous man in Europe.” Reviewers, theologians, and private citizens chimed in, most of them hostile to the notion that all life had not been created in one fell, heavenly swoop. Although Darwin never stated that humans were descended from apes, cartoonists seized the opportunity to put his face on a simian body. Toward the end of his life, criticism abated as more people accepted his views. More books followed, including two revised versions of Origin. His last book, in 1881, was on earthworms.

Many of Darwin’s theories were wrong. A giraffe may stretch his neck to reach those tender high leaves, but he will not pass his long neck to his offspring. The blacksmith’s daughter will not necessarily have muscular arms. But recently Missouri scientists found that Anolis lizards grew different hind limbs and toe pads in response to changing environments. Many of Darwin’s ideas still form the basis of evolutionary belief in the scientific community.

Darwin lived a life of regularity at Down.

“My life goes on like clockwork and I am fixed on the spot where I shall end it,” he wrote. And so he did, dying on April 19, 1882, at age 74. He is buried in Westminster Abbey.

* Originally published in July 2016.

Comments