Gibson Mill, a 19th-century former cotton mill, in secluded woodland at Hardcastle Crags, near Hebden Bridge, West Yorkshire, England.Tom Green / Flickr

Britain once produced half the world's cotton cloth without growing a single scrap of the plant, so just how did British textiles come to clothe the world?

By the middle of the 19th century, Britain was producing half the world's cotton cloth, yet not a scrap of cotton was grown in Britain. How then did Britain come to dominate the global production of a cloth made entirely from material imported from the southern United States, India, and Egypt?

The answer lies in a set of circumstances no less complex than the finely woven, beautifully printed British muslins, calicoes, and chintzes that clothed people and furnished homes everywhere.

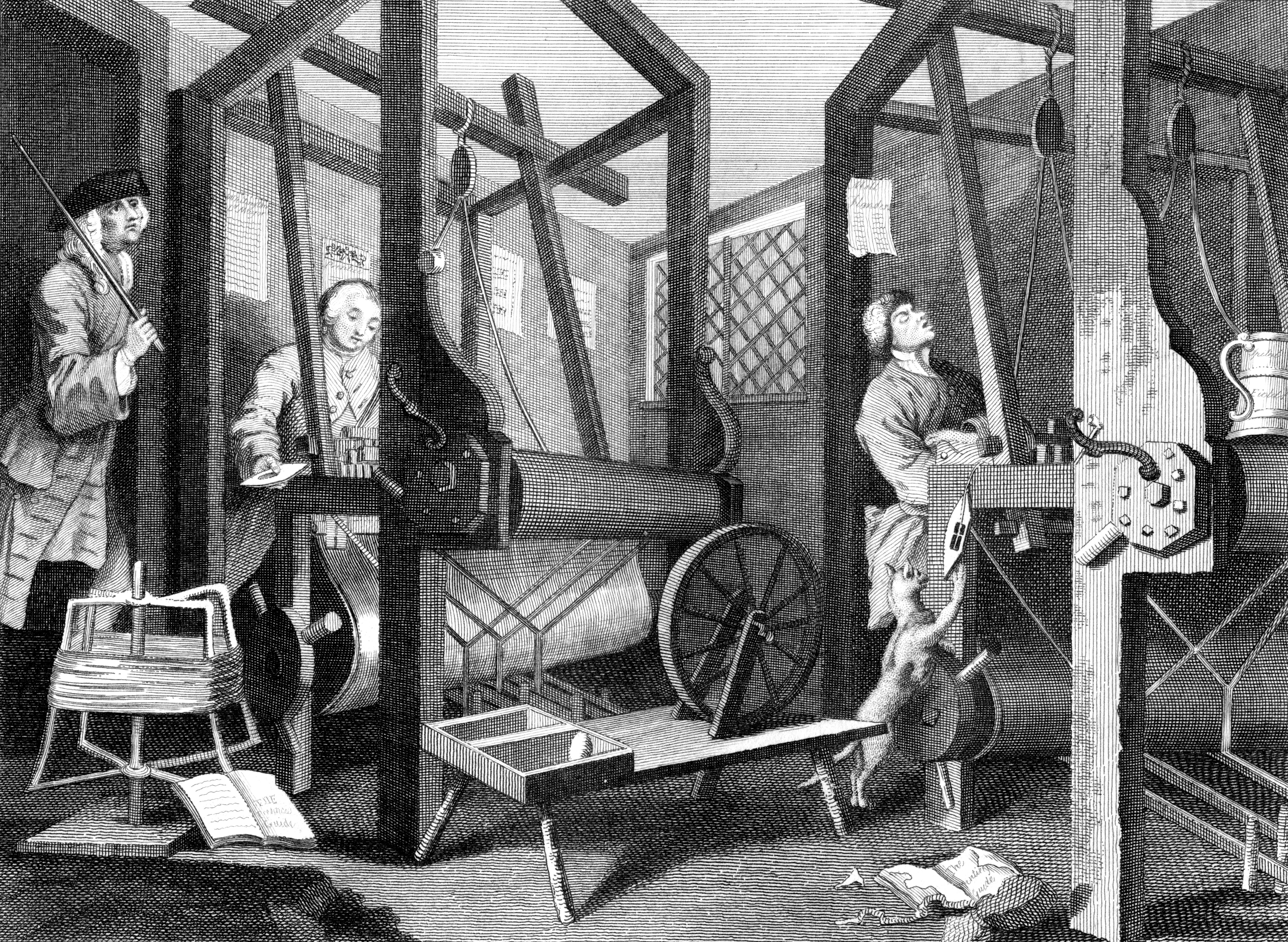

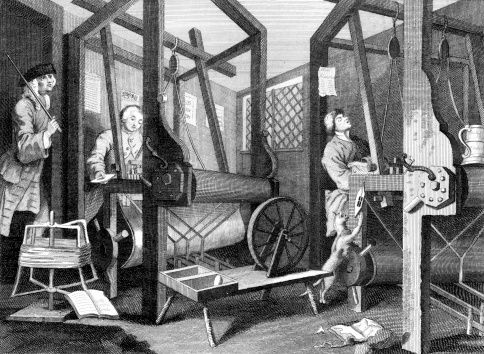

Interior of 18th Century English Textile Mill

Britain had long manufactured textiles

The damp climate is good for grazing sheep, so for centuries, the country was renowned for its fine woolens. Flax, the raw material for linen, also thrives in rain. Linen and wool were used to make the linsey-woolsey worn by all but the richest people in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Silk, introduced by French Protestant silk workers fleeing persecution in the 17th century, was also made in Britain, mostly in London.

Textile workers plied their craft at home, sometimes to supplement farming. Women spun yarn, often helped by children. The yarn then went to a weaver, usually a man, who might be another family member weaving cloth for the household. More likely, both spinsters and weavers worked on the "putting out" system: A merchant supplied the raw fiber and then picked up the finished goods for sale elsewhere.

Traditionally, one handloom weaver needed the yarn output of four spinsters. But by the mid-18th century, many weavers were using the flying shuttle that had been invented by John Kay of Bury, Lancashire, in 1733. By speeding the shuttle across the loom and freeing one of the weaver's hands, this invention upped the demand for yarn; one worker could now weave the output of 16 spinsters. With cloth in demand both at home, where the population was increasing, and abroad, where British colonies were a captive market, improved spinning methods were essential to meet the need for cloth.

The introduction of the Spinning Jenny

Wool production was difficult to mechanize because centuries-old laws protected traditional ways of making it. Conversely, by the 1740s silk was already being machine-made in factories in Derby and Macclesfield with equipment based on pirated Italian designs. But silk was too delicate and expensive for mass consumption. Cotton, on the other hand, was hardwearing, comfortable and inexpensive. Unlike wool, its production was not controlled by ancient practices because it had only become widely available after the East India Company began exporting it from India in the late 17th century. Inventors, therefore, bent their minds to creating cotton-processing machines, and cotton spearheaded the British industry into the factory system.

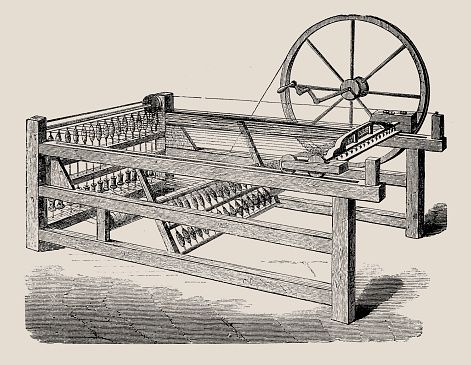

The first major improvement in spinning technology was the spinning jenny, introduced in 1764 by Thomas Highs (1718-1803) of Lancashire and named for his daughter. Highs wanted a machine for spinning cotton that would multiply threads more quickly, and he built a device with six spindles. James Hargreaves (1720-78), who is widely credited for inventing the spinning jenny and was also from Lancashire, apparently improved Highs' design by adding more spindles. Hargreaves acquired the patent for it in 1770, but by then the device had been widely copied. By the time of Hargreaves' death, more than 20,000 spinning jennies were in use. It spun yarn from between 20 and 30 spindles at one time, thus doing the work of several spinsters - a prospect that had made Hargreaves so unpopular in his neighborhood that a mob destroyed his spinning jennies and ran him out of town.

A Spinning Jenny, which proved to be a key development in the textiles industry.

The introduction of cotton

In the 1790s, the first newly planted cotton came from American plantations manned by slaves. The raw cotton had to be cleaned before it could be used by the fast-moving equipment, but it was taking a full day for one person to remove the seeds from one pound of cotton. Eli Whitney, a New Englander, solved that problem with his cotton gin, which used a series of steel disks fitted with hooks to drag the cotton through slots in a grid, leaving the seeds behind. This invention both spurred the Industrial Revolution in Britain and induced Southern planters in America to grow more cotton.

Britain not only had clean supplies of American cotton and an array of machines to handle every stage of making it into cloth, but it also had good power supplies. Eighteenth-century machines typically used water power, hence the siting of early factories near the fast-flowing rivers of the Pennines. But after James Watt invented the steam engine in 1781, coal became the main fuel. Serendipitously, England's richest mines were also near the Pennines in Lancashire, Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire, and Derbyshire. Thus, these northern areas became the textile strongholds of the country.

The new machinery ended the traditional domestic system of textile production. Machines had to be close to their power source; they could not be in cottages. Moreover, different machines sequenced to perform specific tasks required both a division of labor and specialized skills. Workers, therefore, had to follow strict rules about work and punctuality.

Some mills specialized in one textile-making process, but others, such as Quarry Bank Mill at Styal, established in 1784, performed all the needed tasks to turn cotton fiber into cloth. At Quarry Bank Mill, nearly half the workers were children between the ages of 7 and 21, most from workhouses and orphanages who were contracted to work for a period of seven years as apprentices. By 1800 there were 90 children who lived and worked without pay at the mill, learning the trade as the reward for their work, although there was no significant effort to teach them the trade; mostly they were regarded as a source of cheap labor.

The price of child labour

Records from Quarry Bank Mill contain details of nearly 1,000 children who worked there between 1785 and 1847. Their day began early. They typically rose at 5:30 a.m., were given a piece of bread to eat and began work at 6. Through the day, they usually had three short breaks, when they were fed oatmeal, and then at 8:30 p.m., after finishing their shift, they got a supper of bread or broth. On Sundays, they had reading lessons, church, and chores, such as tending the owner's vegetable gardens.

Life was equally hard for adult factory workers. Until 1833, hours of employment were not regulated, and it was 1844 before the law insisted that the machinery had to be fenced to prevent death and dismemberment. The thunderous noise of the machinery never ceased, so most older workers became deaf. Lung diseases were also prevalent, caused by the minute fiber fragments in the air. Few adults could leave the mills, especially when whole cities were devoted to textiles and little other work was available.

Interior of an English textile mill

The start of the American Industrial Revolution

Samuel Slater of Derbyshire responded to an advertisement offering £100 bounties to English mill workers prepared to emigrate to America. He took with him the secrets of the water frame and just as significant the management techniques of continuous factory production that Arkwright and Strutt had pioneered. In America, Slater teamed with Moses Brown, who had been experimenting with machinery in Providence, R.I., and introduced him to the water frame. In 1790, they built a new water-powered factory in Pawtucket, R.I., and in 1797 Slater built the White Mill on the Blackstone River and later a workers' village called Slatersville.

Francis Cabot Lowell of Massachusetts traveled to England in 1810 to tour Manchester's mills, just as they were being fitted with power looms. He gleaned enough so that in 1814 he built the first mill in America capable of transforming raw cotton into finished cloth, located on the Charles River at Waltham, Mass. Four years after Lowell's death in 1817, the firm moved to a site on the Merrimack River, where a new town named Lowell in his honor soon became the center of America's cotton industry.

The spinsters leave

By 1840 Lowell had 10 mills employing more than 40,000 workers, mainly young women. Many were from England. The textile business in Britain, though successful, went through economic cycles. The 1840s were so grim that they were known as the Hungry Forties, and even after the Civil War ended in 1865, American cotton supplies were uncertain and unemployment remained high. Many textile workers therefore emigrated. English immigrants staffed the sorting rooms of the mills in Lawrence, Mass. Contingents of immigrants from Lancashire went to the mills of New Bedford, Mass., and silk workers from Macclesfield in Cheshire left for Paterson, N.J. -- a town often called Silk City, as was Macclesfield.

Today, the sturdy brick mills built to house the massive textile machinery still stand throughout New England and northern Britain, all turned to new uses. Among those that can be visited in Britain are Quarry Bank Mill, now a magnificently preserved National Trust property; Titus Salt's village of Saltaire in Morley, Yorkshire; and Paradise Mill and the Silk Trail at Macclesfield, Cheshire. There remains one original water frame, at the Helmshore Museum, and a quarter of it works, powered by electricity since the museum does not yet have a working water wheel. These 18th- and 19th-century devices express both the engineering achievements of their inventors and the difficult lives of those who operated them.

Read more

* Originally published in June 2018.

Comments