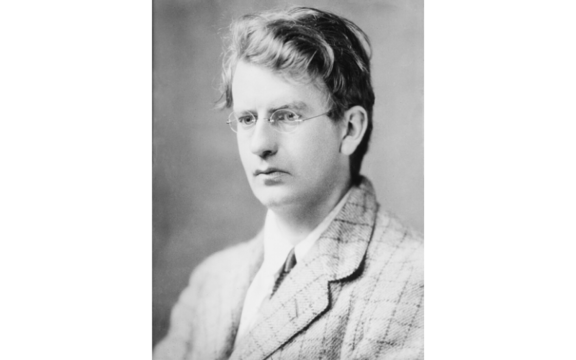

The inventor of television, John Logie Baird.United States Library of Congress.

John Logie Baird, the forgotten pioneer of television, first demonstrated his invention, the colour television, changing the world forever.

"A potential social menace of the first magnitude!" proclaimed Sir John Reith, first Director-General of the British Broadcasting Corporation, describing John Logie Baird's 1926 invention: television. Reith also compared the new medium's social impact to "smallpox, bubonic plague and the Black Death."

Of course, billions of TV viewers today would disagree with his description.

John Trenouth, Senior Curator of Television at the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television in Bradford, North Yorkshire, explains that "the reason we have this and much more of Baird's equipment is that we not only acquired the Kodak Museum collection and the Royal Photographic Society collection but also all the television technology from the last three-quarters of a century, including Baird's. And now we have the largest collection of television technology in the world!"

The Museum plays host to a massive array of essential artistic and the technological elements associated with the photography, film, and television media.

"I've got less than .1% of it on display," Trenouth notes.

Although much of the collection is stored in the Black Dyke Mill not far from the museum, 'the really big stuff is stored in the Science Museum's disused Second World War aircraft hangars.'

During the early decades of the last century, Baird was one of several inventors in Germany, Hungary, France, Great Britain, and the US who were in a neck-and-neck race to claim the title of 'first' to develop the technology to transmit and receive moving pictures, television. It was Baird, however, whom Britain recognizes as the pioneer who was the first in the world to demonstrate the technology as early as 1925.

Baird most likely never imagined the impact of his work and how it would ultimately change society, culture, and the world.

While a visit to the MPFT, which houses much of Baird's early apparatus, answers many questions about the inventions, the man himself remains an enigma.

Pointing out one of the gems in the Baird equipment collection, which is stored in a below-level area at the Museum Trenouth points to "the world's most expensive pile of scrap. It's a fake - but faked by Baird himself."

Trenouth explains: "Baird, whose system was mechanical, would in ten years"' time be in competition with a rival system, which was electronic, proposed by EMI [Electrical and Musical Industries, Ltd., a British entity with a strong relationship, including patent sharing, with RCA].

Associates of Baird suggested that he donate his original apparatus to the Science Museum in London, thereby reinforcing his position as the premier scientist, engineer, and the true inventor of television, quashing anyone else's claim to the title.

'The only problem was,' continues Trenouth, 'that the original [transmission apparatus] no longer existed. Baird, in his frugal Scot's manner, reused parts as he improved the design of the mechanism. He cobbled together something that used many of the original pieces.' As he points to various parts of the ersatz device, Trenouth clarifies, 'We know that the motors are original and the discs are original, but the baseboard, originally a coffin board, is not.'

Typical of Baird, who was obsessed with anyone having access to his work, he built the 'fake' so it wouldn't work. 'The arrangement of the machine would actually stop it from working,' explains Trenouth. 'He was terrified that when it went on display someone would walk out with the plan.' Born in 1888 in Helensburgh, Scotland, not far from Glasgow, Baird became interested in electricity early in life. With a homemade generator, he electrified his parents' house and set up a telephone system between his home and those of some of his school chums. He was greatly influenced by science fiction writer, H. G. Wells, particularly The Sleeper Wakes.

After studying at the Royal Technical College in Glasgow, he earned a diploma at Glasgow University, but his studies came to a halt at the outbreak of World War I. He volunteered, but was deemed unfit for duty due to a recurring chest illness he contracted as a baby and which left him vulnerable to colds and flu throughout his life.

He turned to a some odd commercial ventures, including the Baird Undersock 'for soldier's foot' and the Speedy Cleaner, a 'revolutionary soap.' He even ventured to Trinidad, hoping that the warmer climate would benefit his health and financial state. He started a jam-making business in Port of Spain, but returned home after failing the business failed and he suffered a bout with malaria left him then left him both weakened and demoralized.

It was when he moved to Hastings in the early 1920s that Baird began serious work on ideas he'd had about the transmitting and receiving of pictures.

According to Trenouth, whose background is in physics, electronics and technology, 'Baird was not a scientist in the strict sense of the word. He had a lot of ideas, and he could sketch out what he wanted - even on tablecloths in restaurants, where,' he laughs. 'They had to put the cloth on the bill so he could take it away with him!'

The system that Baird selected - from several possibilities available to him in that technologically distant past - was one that used a disc with apertures cut into it, which scanned the image to be transmitted. A 30-line picture (compared to the 600-plus lines today) was repeated 12 1/2 times per second. Not only was it small, but it also flickered. But it was eminently suitable for the head and shoulder shots, just as on web-video today.

As with every inventor, Baird had assistants. One of these assistants still stares at the equipment in which he was used for an early experiment. 'Here is the original Stooky Bill,' points out Trenouth. He gestures toward the head of a ventriloquist's dummy. 'Because the lights for the experiments were so hot, Baird couldn't use a human for the tests. So Stooky Bill was 'recruited.'' His hair is singed; his face is cracked; and his lips are chipped, but he is still smiling. Stooky Bill's visage ('stooky,' also spelled 'stookie,' is Glaswegian slang, according to Trenouth, for someone who is wooden in his movements; it is also a plaster-of-paris which is used to immobilize bone fractures; hence, immovable) was then transmitted from room to room in Baird's laboratory at 22 Frith Street in London.

'If only we could interview Bill, what stories!' muses Trenouth.

One of Baird's early engineers, Thornton (Tony) Bridgewater, who became the BBC's chief engineer in the 1960s, could tell stories. 'Baird was an absolute charmer,' he told Trenouth in a late-in-life interview. He also told the story about Baird's typical greeting upon visiting him in the laboratory: 'Have you anything to show me?' he'd say. Bridgewater revealed that Baird might take him for dinner at the local Lyons Corner House, drawing on the tablecloth during the meal, then hand it over to Tony saying, 'Have this working for me in the morning.' And Tony would have to work all night!

The first demonstration of true television anywhere in the world occurred on 26 January to invited members of the Royal Institution. The same year the inventor formed the Baird Television Development Company, he made demonstrated long-distance transmission from the London area to Glasgow in 1927, made in direct response to an AT&T demonstration between New York and Washington, D.C., a mere 250 miles. Baird's was a 400-mile transmission.

In early 1925, Gordon Selfridge, Jr., scion of the famous department store founder, came to see the latest developments. The young Selfridge was looking for something that would attract customers to the family department store during its anniversary celebration in early 1925 and also create some interest from the press. Selfridge was impressed by Baird's television system and made the inventor an offer he couldn't refuse: for 50 guineas a week, Baird would demonstrate his apparatus in the Oxford Street store three times a day for three weeks. Selfridge's was able to boast in a newspaper advertisement in April 1925 that it presented 'the First Public Demonstration of Television in the Electrical Section (First Floor)...'

Both Selfridge and Baird benefited from the presentation: Selfridge's garnered the publicity and the inventor had a means for promoting his work, and also obtained badly needed funds to continue his work.

Baird received more headlines when Ben Clapp, one of his colleagues, sailed to New York, and in early 1928. From Clapp's home in Surrey, Baird broadcast a picture of a moving head across the Atlantic and it was received in Hartsdale, a town just outside New York City.

Between 1930-32, Baird accomplished a trio of firsts. At the Coliseum cinema, now the home of the English National Opera, Baird transmitted a 3x6 foot image, an early example of 'large-screen television.' He also 'broadcast' from the Derby finish line at Epsom to both an audience at the Metropole cinema in London, and to those few who had purchased receivers; this was considered the first 'remote' broadcast of television images. And during the famed running of the horses in 1932, he broadcast the race on a large screen at a pair of London cinemas.

If anyone had purchased a receiver,' says Trenouth, 'they would have had to spend about 25 guineas, a huge sum and not within reach of the general public.' Later, there were 'do-it-yourself' kits which could be purchased for considerably less and assembled by the buyer.

Television historians consider this the first time an outside event had been broadcast.

'Talk about clever,' says Trenouth. 'Baird called his transmission equipment a'scanner' because it scanned the image. For the Derby he mounted it in a caravan and shot the scene in a mirror mounted on a door of the van. By hinging the door open and closed, he overcame, somewhat, the problem of panning the action.' To this day in Britain, the outside broadcast trucks that the BBC used are called'scanners.'

Baird appeared to the public as the quintessential absent-minded professor: shortsighted; wearing rimless glasses; shaggy hair; so focused that he often forgot to eat or shave; and often seen wearing a heavy overcoat, muffler, and spats, even in the warmest weather, to ward off a chill. He was still susceptible to the persistent illness that, over the course of the next decades, would hamper his work and business arrangements, including those with the British Broadcasting Corporation.

He continued to develop an amazing array of ideas. Besides those already demonstrated, he devised 3D television and color television, demonstrated in 1928.

'And here we have Eustace, the equivalent of Stooky Bill, but used for the color experiments,' Trenouth points out.

One of the most spectacular of Baird's accomplishments has only recently established him as the forerunner of the video recording industry but not credited with the technology. Despite the fact that an American company, Ampex, is often recognized as the inventor of the video recorder in 1946s, it was actually Baird who made such a recording starring in 1927, again starring Stooky Bill. Baird, who called the process 'Phonovision,' could record on wax discs, which look something like 78-rpm gramophone records, but he couldn't have seen recognizable pictures on playback because there was so much distortion and noise. Don McLean, whom Trenouth describes as 'an industrial archaeologist for the electronic age,' developed computer software tools capable of restoring the picture some 20 years ago.

'There are six extant discs. We have the first, which belonged to one of Baird's engineers,' says Trenouth.

According to McLean, another three are dated 10 January 1928. Two of them are at the NMPFT, and the other is housed at the Royal Television Society.

'The last, dated 28 March 1928, of Mabel Pounsford, a secretary to Baird, is in private hands,' notes McLean.

Baird was living in comfortable circumstances by 1931 and had a reputation as a noted inventor and engineer. He'd had a long relationship with a mysterious married woman for several years, but he realized that, at 42, he should begin to think about the next step in his personal life. It took a dramatic and romantic direction when he met Margaret Albu, a concert pianist 19 years his junior. After a three-month courtship, they were married in a New York, where Baird had been negotiating with several potential financial backers. He was dressed in robe and slippers for the ceremony, as he had, again, become ill. A daughter, Diana, was born in 1932, and a son, Malcolm, arrived three years later.

By now, not only had Baird developed the technology for transmitting television and had also designed the device to receive the picture, a television set. Both inventions going back to the mid-1920s!

'If we jump ahead a bit to the next major event in the history of television,' suggests Trenouth, 'we know that Baird realized that to make television a viable option as a medium, he would have to develop a relationship with the broadcast giant, the BBC.' The head of the broadcast giant was someone whom Baird had inadvertently slighted decades earlier at school in Scotland, and that person, John Reith, held a grudge. Although he later admitted to a mild respect for Baird, Reith made many attempts to destroy the relationship between the BBC and the inventor.

In what Trenouth describes as 'true government fashion,' aboard was organized, the Selsdon Committee. Their task was to investigate systems suggested from those submitted from around the world. They narrowed the selection to two, both British, the only ones that could be demonstrated as working. One was Baird's; the other was from EMI, now Marconi-EMI. The Committee could not agree which system should be awarded the contract with the BBC; a competition between the two systems was instituted. Every other week, the BBC would broadcast the alternate systems each evening for six months...and then they would decide which was best.

According to Simon Vaughan, archivist of the Alexandra Palace Television Society, the first 'public' broadcast occurred during August 1936 from Ally Pally. The identical programme was transmitted twice a day to the annual National Radio Show at the Olympia, and included singer Helen McKay, a pair of acrobatic tap dancers, as well as Miss Lutie and Pogo, the wonder horse. Transmission was from the Baird studio and the Marconi-EMI transmission from the other one.

The official launch began at 3 p.m. on 2 November 1936, with broadcasts from Alexandra Palace. A former Edwardian entertainment complex, it was chosen because it is high on a hill overlooking London. The building still stands and hosts a variety of events. The Baird Company's system was used for the opening broadcast.

The inaugural programme on the BBC included a series of speeches, including one from Lord Selsdon himself, notes Vaughan. A cinema newsreel began the opening program followed by musical comedy star Adele Dixon singing 'Television'; the American comedy dance team of Buck and Bubbles, the first African-Americans to appear on television; and a series of vaudeville-type acts. The service was offered to viewers from 3 to 4 p.m. and again from 9 to 10 p.m.

Vaughan points out, 'It was acclaimed as the first fully public service in the world because the high-definition television receivers were on general sale, and the service was recognized by the government, the Post Office [which had to sanction such broadcasts] and the BBC as a permanent entertainment medium.' 'Keep in mind,' he continues, 'that the number of sets available to receive this new service was less than 400 and the range of the transmitter was between 30 and 50 miles from Alexandra Palace. There was a 1,000-pound allocation for the programmes for the week, 'with no television on Sundays!'

Trenouth approaches a huge apparatus, saying, 'And here is the camera that Baird used in the 1936 experiments that first time.' And he explains the process: 'Baird used the 'intermediate film system.' What he did was actually film the program. The film came out of the bottom of the camera and went directly into the developer, into a fixer and while it was still wet and underwater, 58 seconds later, it was 'telecined' into a TV picture. But it was complete madness!' he exclaims.

There were so many problems: noise, was one; limited pan and tilt because of the large pipe where the film came out, and again, 'the Scot's thriftiness was evidenced as Baird modified the camera to 17.5mm, half the width of 35mm, getting twice as much for his money! To make matters worse, as the film with its sprocket holes was dragged into the water; it dragged air bubbles with it, which became lodged in the sound head. So halfway through the program, there was a burbling sound.

'Now comes the funny bit. They had a very high-tech solution to the problem,' says Trenouth with a tinge of sarcasm. 'A technician with a cricket bat would whack the side of the tank to dislodge the air bubbles. So, first, the viewers heard the burbling and then a peal of thunder and the sound was restored...until the next burbling and thwacking!'

There were other complications, but 'the really sad thing is that someone told Baird a lie. He was told that he could store the film and reshow it. So, where are all those programmes? He was told that he didn't need to dry the film, that he could store it wet. So everything is lost...except 16 frames,' Trenouth says sadly.

Although the trial was supposed to last six months, it was obvious that only one system would work, and it wasn't Baird's. He was devastated, even though by 1936 Gaumont-British had taken over his company and he was relegated to working on his own at his home in Sydenham. 'He had a laboratory built on the side of his house where he devised another set of devices during World War II,' says Trenouth. 'One was the Telechrome tube, the first color tube that didn't use anything mechanical. And the NMPFT has the only surviving Telechrome tube in the world.'

Trenouth, who has been with the Museum for twenty years, notes that it wasn't just television technology that was new, but the vocabulary of the new no one knew what to call people who watched the new technology. Initially, they were called 'lookers in.' Then The Daily Mail invited its readers to submit an appropriate designation for those who watched the medium. Some entries included 'audiovisor' and 'audioseer.' Oddly enough, although one of the suggested names was 'viewer,' it was thrown out. Of course, today it is the only one we use today.'

Baird's health declined and the family moved to Bexhill-on-Sea, Surrey, where he continued his work. He continued developing his ideas throughout World War II but the evidence of his contribution to the war effort has never been confirmed.

Baird, who died of pneumonia at the age of 56, has never received any formal accolades. To many people, he had been 'tarred with the brush of failure,' according to Trenouth. According to McLean, however, 'Baird was a legend in his own lifetime, at least until the start of high definition television service in 1936.'

John Logie Baird's legacy to the medium of television is kept alive and presented with respect at the NMPFT. Some may quibble about the significance of his 'firsts.' The term 'father of television' may be a misnomer to others, but with 177 patents to his name, the term 'inventor' goes unchallenged. What he did accomplish under the direst of personal and financial circumstances is preserved for 'viewers' to see.

Several plaques have been erected to commemorate his contributions. The one on Station Road, Bexhill reads;

John Logie Baird

The Pioneer of Television.

* Originally published in June 2018.

Comments